Like Halprin: Passonneau had a vision for Charlottesville

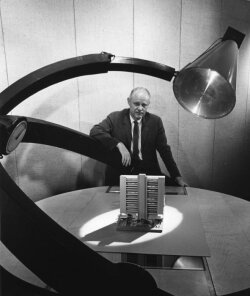

Joseph Passonneau, a renowned American architect-engineer, died in Washington, D.C. in late August at the age of 90. Among his accomplishments was his design of I-70 through Glenwood Canyon in Colorado as well as his ability to persuade a timid St. Louis political hierarchy that the controversial Arch would be a successful gateway to the West.

In the late 1980s, Passonneau also worked on Charlottesville’s gateway: U.S. 29 North. In fact, his proposed urban expressway became so controversial that “expressway” became a pejorative word in Charlottesville transportation lexicology. It shouldn’t be.

In his 1988 report, Passonneau pointed out that it was possible to design “large urban roads that delight the communities in which they are built,” and he envisioned such an expressway for through traffic on 29 with adjacent and parallel landscaped local traffic lanes. (The recent Places 29 Plan proposed a similar design but avoided the “expressway” term.)

Passonneau analyzed the various bypass pathways, including his own adjustments to an urban expressway expediting southbound traffic through Charlottesville and connecting to 29 South via the 250 Bypass. The design built on the so called “base case” traffic improvements of grade-separated interchanges to foster the flow of local east-west auto and pedestrian traffic at Hydraulic and Rio Roads with crossover roads at other points like Greenbrier Drive and Shoppers World.

Such an urban expressway, Passonneau pointed out, would take 242 fewer acres than the proposed bypass, destroy no residences, farm, forest or subdivision land, and impact less business land than any of the bypass pathways. Certainly, an urban expressway would be the least environmentally-damaging option.

Despite Passonneau’s vision, neither he nor his proponents (the Piedmont Environmental Council and Supervisor Tim Lindstrom among the most vocal) could convince the powerful North 29 business owners that a more attractive roadway not only would provide a better solution for local and through traffic but also would serve long term economic interests by creating a more attractive 29 business district. After all, in addition to the local lanes along 29, the network of parallel roads to serve local traffic would include Hillsdale and Commonwealth Drives. That would allow development of an expanded business district– not just the 29 strip.

At the time, however, the 250 interchange flyway, perhaps most controversial piece, was criticized as having too large a footprint. Yet Passonneau had designed it and the rest of the roadway to national safety standards, not to VDOT’s more gargantuan scale. In fact, the 1988 design has no larger a footprint than the Bypass/250 flyway now proposed (and shown in 3D modelling on the Charlottesville Tomorrow website).

Passonneau's urban expressway (and its later version in Places 29) were nixed largely by those representing local business interests, which have evidenced in the 29 discussion little imagination, creativity, or commitment to the region's long-term economic health.

Glenwood Canyon above the Colorado River was a far more difficult engineering challenge and an even more controversial project. Nevertheless, Passonneau’s design preserved and even improved on the terracing above the Colorado River, weaving a 12-mile highway through tunnels and bridges to complete I-70. The result is a beautiful, functional, and scenic highway, which earned Passonneau a Presidential Award for Design Excellence.

Here, in Charlottesville, state politicians have engineered (pardon the pun) a political decision to build a western bypass that will cut through the rural landscape, including Stillhouse Mountain and the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir, impact beautiful residential areas and several schools while spending between $240 - 500 million of taxpayer dollars for just six miles of road ($40/million a mile at the lowest estimate)– while removing just 10 percent of the traffic from 29 Business. The interchanges, by contrast, would cost $40-50 million apiece.

If we want a real solution to local and state traffic issues through Charlottesville, one need look no further than to the vision of Passonneau. If Glenwood Canyon could benefit from this excellent designer-architect, why shouldn’t Charlottesville get a landscaped gateway that welcomes visitors to the uniqueness of Jefferson’s country?

Over 35 years ago, Charlottesville invited another visionary, landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, to design the Downtown Mall. Despite naysayers in the business community, the Mall thrives thanks in large part to Halprin’s vision and the leadership of the two Councilors who voted aye on the then-controversial issue: Charles Barbour and Mitch Van Yahres.

An urban expressway on 29 would transform an Everyplace USA strip mall road to vindicate Passonneau’s vision, but more importantly, it would be a true testimonial to the long range vision of our local and state leaders.

Will the expressway design be revived? Probably not.

But imagine what could happen if we could scrap the special interests to execute a truly win-win solution not only for transportation and beauty, but also for business, for the community, and for the Commonwealth.

~

Kay Slaughter was elected to City Council in 1990 and served as mayor from 1996 to 1998. Last year, she retired from her day job as an environmental attorney.

5 comments

I agree with Kay Slaughter that the proposed by-pass is a bad idea and that an expressway in the existing path of 29 North would be by far the best solution to problem of speeding through traffic. I have to wonder though where she imagines a pipeline to carry water to the Ragged Mountain reservoir might run. She's an advocate of that foolish plan.

Without a route for a pipeline, building a huge dam at Ragged Mountain is nothing more than a huge environmentally unsound boondoggle. A right-of-way along the by-pass is far from assured, but is still the most likely place for the pipeline which will be absolutely necessary for a new reservoir to work.

Also, Passonneau seems to have had a sensible plan for dealing with traffic on 29 North, but boy did he screw up St. Louis. http://timothyblee.com/2010/07/22/the-anti-urban-20th-century/ A reference to him and his legacy might have been more appropriate in an article showing how destructive the outdated thinking behind the Meadowcreek Parkway has been in places where that has been tried.

Ah, but the real question is: Why do we drive on a parkway and park in a driveway.

why you say we in what we on and on what we in?

cookieJar:

Thanks much for the interesting link.

And speaking of "the outdated thinking behind the Meadowcreek Parkway," do you remember the equally ill-thought Huja Highway (as critics called it)? That was the city-severing throughway that chief city planner Satyendra Huja wanted to create several decades ago between Ridge Street and Jefferson Park Avenue along the south side of the railroad tracks.

Such a road would, of course, have resulted in the demolition of dozens of houses and the subsequent depression of property values and depletion of civic mass in the adjacent neighborhoods. Most perniciously, though, it would have radically exacerbated Charlottesville's north-south divide. With it in place, the wrong side of the tracks would have become an even wronger choice of address.

Fortunately, that idea has remained dormant long enough to see south-of-the-tracks property values rise and civic mass increase to a degree that would make its resuscitation unlikely even with Huja as mayor (as he's likely to become). But even unbuilt, it has had negative effects in the form of parcels that were rezoned in anticipation of its construction.

For instance, people often ask me how BAR and/or Planning Commission could have allowed construction of the Purple People Eater -- the massive Bill Atwood-designed excrescence crammed sideways onto what had been the site of a single modest house on Fifth Street S.W. The answer is that the project was subject to no design or even bulk control because the parcel was zoned Industrial. And that was the case because it had been on the planned route of Huja's memorial parkway.

(It should be noted that Huja did succeed in creating the major traffic sluice -- aka Roosevelt Brown Boulevard -- that twice daily turns Cherry Avenue into a heavily polluting parking lot that prevents neighbors pulling out of their own streets. In addition, it has served as an excuse for numerous project approvals that have resulted in numerous house-demolitions along its course.)

In theory, completion of Meadowcreek Parkway, which Huja has always supported, will make Ridge Street another such sluice. Given that Ridge is already often at gridlock, however, it can be foreseen that much of the new traffic will trailblaze down Ridge's narrow tributaries in search of the ever elusive short cut and thereby undercut the property values and civic mass so recently bolstered.

Hey, I like the Purple People Eater. I used to walk by it every day. It's interesting, and there are already plenty of "single modest houses" around. Also, I may be getting my history wrong, but I was under the impression that the route along the tracks was intended to be a greenway mostly catering to bike/ped uses, not a "highway" as you've described it. Am I wrong about this?