Just say know: Tim Wilson wants to change the world-- one story at a time

-

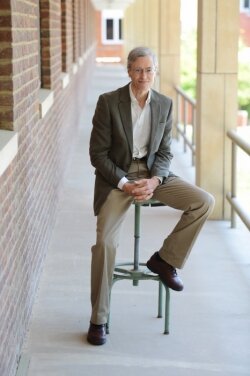

![%2526quot;My biggest beef is that we implement these [social] programs widely before they are adequately tested,%2526quot; says Tim Wilson. %2526quot;Why not test them first with rigorous studies, find out what works best, and then implement them?%2526quot; %2526quot;My biggest beef is that we implement these [social] programs widely before they are adequately tested,%2526quot; says Tim Wilson. %2526quot;Why not test them first with rigorous studies, find out what works best, and then implement them?%2526quot;](/files/imagecache/partial_width/images/field_images/facetime-wilsontimothy2.jpg) "My biggest beef is that we implement these [social] programs widely before they are adequately tested," says Tim Wilson. "Why not test them first with rigorous studies, find out what works best, and then implement them?"PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"My biggest beef is that we implement these [social] programs widely before they are adequately tested," says Tim Wilson. "Why not test them first with rigorous studies, find out what works best, and then implement them?"PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO -

"The idea is to "redirect" people's stories in a positive way," says UVA psychology professor Timothy Wilson, and author of the book Redirect. "Sometime it means just making small tweaks in their narrative."PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"The idea is to "redirect" people's stories in a positive way," says UVA psychology professor Timothy Wilson, and author of the book Redirect. "Sometime it means just making small tweaks in their narrative."PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO -

"Imagine giving a talk on physics, in 1910, and saying 'you know, there's this thing called relativity,'" wrote journalist Malcolm Gladwell about a talk he gave at UVA, with Wilson in the front row, "and then spotting Einstein in the front row."Kris Krüg

"Imagine giving a talk on physics, in 1910, and saying 'you know, there's this thing called relativity,'" wrote journalist Malcolm Gladwell about a talk he gave at UVA, with Wilson in the front row, "and then spotting Einstein in the front row."Kris Krüg -

"When people structure their problems into a narrative," says Wilson, "they can let it go."Jen Fariello

"When people structure their problems into a narrative," says Wilson, "they can let it go."Jen Fariello -

"Tim demonstrates in Redirect how some of our most cherished public programs fail the tests that measure their efficacy, and yet continue to receive support," says Daniel Gilbert, a Harvard professor of psychology and Wilson's long-time research collaborator.Courtesy Daniel Gilbert

"Tim demonstrates in Redirect how some of our most cherished public programs fail the tests that measure their efficacy, and yet continue to receive support," says Daniel Gilbert, a Harvard professor of psychology and Wilson's long-time research collaborator.Courtesy Daniel Gilbert

UVA psych professor Timothy Wilson's book Redirect: The Surprising New Science of Psychological Change begins with a horror story. A police officer in Florida is the first to arrive at a house engulfed in flames. There are screams for help coming from the structure, and through a window the officer sees a trapped man. The officer tries to break down the heavily bolted front door, but when it finally gives way, it's too late.

"He was curled up like a baby in in his mother's womb," says the officer. "That's what someone burned to death looks like."

The next day, when the officer reads the local newspaper, he realizes the victim was a friend. The officer couldn't sleep or eat, and so his superiors scheduled a Critical Incident Stress Debriefing, which is basically a therapy session with professional counselors designed to prevent post-traumatic stress disorder. Survivors of the 9/11 attacks and the 2007 Virginia Tech shootings underwent similar interventions.

Sounds like the compassionate, common sense things to do, right? Express yourself and work through the trauma so that you don't repress the feelings.

The problem is it doesn't work. Four years after the fire, Wilson alleges, the police officer was still haunted. As Wilson reveals in Redirect, such post-trauma debriefings not only don't help, they may even cause psychological problems.

"Tim demonstrates in Redirect how some of our most cherished public programs fail the tests that measure their efficacy, and yet continue to receive support," says Daniel Gilbert, a Harvard professor of psychology and Wilson's long-time research collaborator. "Tim is begging us all to be empiricists– to develop ideas to change the world for the better but to submit those ideas to empirical scrutiny and then cast them aside when they prove ineffective."

Wilson takes aim at many widely implemented social programs, including D.A.R.E (Drug Abuse Resistance Education), Healthy Families America (a popular home visitation program to prevent child abuse), and Scared Straight, the renowned program that supposedly scares at-risk kids away from a life of crime.

"Reliable studies have shown that these programs are largely ineffective," says Wilson, "but they continue to be funded."

Indeed, D.A.R.E America, which originally took its cue from Nancy Reagan's "Just say No" campaign back in the 1980s, has enjoyed enormous support at the local, state, and federal levels. It's estimated that the non-profit program– which gets police officers to administer multi-week anti-drug classes– is administered in 80 percent of America's school districts with an annual cost of nearly $1 billion, much of it covered by government grants.

About a decade ago, information began to surface that showed the program was ineffective and could even lead to future drug use. For instance, the results of a 10-year study published in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology showed that D.A.R.E. was no more effective than no program at all. One thousand 10-year-olds had been surveyed about their drug use and self-esteem; ten years later, the same kids were surveyed again. The results: the kids who'd been in D.A.R.E. were no less likely to smoke pot, drink, or succumb to peer pressure than kids not in the program.

As Wilson points out, random assignment studies (those that compare those who participate in social programs with a randomly-assigned control group), are the "gold standard" in social science research. One such study in 2009 found that after four years 31 percent of kids who went through the D.A.R.E. program used marijuana– the exact same percentage as kids who didn't go through the program.

"To their credit, the D.A.R.E. organization finally heeded the evidence and revamped their curriculum with the Keeping' it Real program," says Wilson.

Indeed, under heavy criticism, D.A.R.E. began implementing the new program developed by Penn State researchers, which takes a page from Wilson's research by using a "narrative" approach.

The new approach "prepares children to act decisively, confidently, and comfortably by teaching them how to say no in difficult situations," according to public statements by D.A.R.E. executive director Francisco Pegueros. "Students also learn how to recognize risk, value their perceptions and feelings, and make choices that support their values," says Pegueros.

But Wilson remains skeptical.

"To my knowledge, this program has never been evaluated rigorously when used by D.A.R.E., that is when police officers deliver the program," says Wilson. "This worries me, because as I speculate in Redirect, it may be that at-risk kids are not easily reached by law enforcement officers."

Of course, D.A.R.E officials are quick to defend.

"I know what D.A.R.E. has done for so many children," says Scott Gilliam, the group's director of training, who bristles at Wilson's skepticism. "I know how communities have benefited by this early introduction to a police officer in a positive light. I have also discovered how research can produce almost any outcome based on how it is set up."

Such sentiments are common with popular social programs, says Wilson, and there's no reason not to believe that kids, communities, schools, and police departments have developed more positive relationships. But the leading random assignment studies over the years, says Wilson, have shown that the program has been largely ineffective.

Same goes for Scared Straight, the popular program designed to keep at-risk youth out of trouble by taking at-risk youth into prisons to get yelled at by hardened criminals, who "scare" them into realizing what a life of crime really entails. Not only have several random assignment studies demolished the efficacy promises of Scared Straight, the studies indicate that participating actually increases the likelihood of criminal behavior.

"My biggest beef is that we implement these programs widely before they are adequately tested," says Wilson. "Why not test them first with rigorous studies, find out what works best, and then implement them?"

In Redirect, Wilson likens the use of D.A.R.E, Scared Straight, and other programs to the old medical practice of "bloodletting," once widely believed to be a cure for various illnesses but one which, as Wilson points out, likely hastened and possibly caused the death of George Washington, who, suffering from a throat infection, had nearly a gallon of blood drawn.

Wilson believes the same phenomenon is in play with certain popular social programs, which seem to make sense to their founders and continue to get implemented because they are popular. Eventually, good science stopped the practice of bloodletting, and Wilson hopes more good science will lead to the implementation of social programs that actually work.

So what does work?

Says Wilson: "story-editing interventions."

Story editing?

"The idea is to "redirect" people's stories in a positive way," explains Wilson. "Sometimes, it means just making small tweaks in their narrative."

That's it?

Wilson nods.

As Wilson explains in Redirect, had the traumatized Florida police officer instead been asked to write a narrative about his experience to bring it into clear focus over a four-day story editing program developed by researchers, his trauma might not have haunted him for so long.

"When people structure their problems into a narrative," says Wilson, "they can let it go."

For instance, Wilson highlights a program called LifeSkills Training. It was developed in the early 1980s to reduce drug and alcohol use by giving kids actual projects to improve self-esteem, plus tips on overcoming shyness and being more assertive. Instead of "scaring" kids into avoiding drug use and at-risk behavior, the program offers practical advice and information.

For instance, kids are shown actual research that social approval of cigarette and drug use is in decline and that the number of kids abusing drugs isn't as high as they've been led to believe. Wilson says that random assignment studies have shown the program to be "significantly effective" at reducing drug and alcohol use among high schoolers.

Other studies have shown that simply performing volunteer work in their communities can lower drug use and at-risk behavior among teens. As for child abuse, Wilson says that story-editing can work for parents at risk of becoming abusive. Such parents, "reinterpret why their children act up," says Wilson.

"Many people think science is something that happens in a lab and involves beakers and test tubes," says Gilbert. "Tim shows how we can– and why we must– use science to evaluate the stuff of which our everyday lives are made."

Who is Tim Wilson?

When journalist Malcolm Gladwell was a fellow at UVA's Batten Institute in 2005, he was at the top of his game. His books The Tipping Point and Blink had both sold over two million copies in the United States and gone on to become international best sellers. In both books, Gladwell used new research in the social sciences to reveal some unexpected consequences of human behavior. During a talk he gave at UVA, however, a mild-mannered UVA psychology professor sitting in the front row unnerved the famous author.

"I had the distinctly uncomfortable feeling, half way through," Gladwell would later write, "that I was simply giving the audience a kind of popularized version of Wilson's own work."

Gladwell would admit that Wilson's research had had a profound influence on his own work and that Wilson's first book, Strangers to Ourselves, was “probably the most influential book I've ever read.”

"Imagine giving a talk on physics, in 1910, and saying "you know, there's this thing called relativity," wrote Gladwell about his UVA experience, "and then spotting Einstein in the front row."

Wilson, like Gladwell, has a knack for exposing the ways in which we deceive ourselves, sometimes by playfully deceiving readers (and study participants) with their own preconceptions, before revealing, as if by sleight of hand, that things aren't what they seem.

"One of the biggest changes in psychology in the last couple of decades has been our discovery that most of what we do is guided unconsciously," says Gerald Clore, a colleague of Wilson's at UVA. "The reasons we give for our choices, even when accurate, are not so much insights as after-the-fact constructions. This idea, only now commonly accepted in psychology, was shown experimentally by Wilson over thirty years ago."

"Just as extraordinarily famous people can get away with having one name (Leonardo, Aristotle, Madonna), Professor Wilson produces experiments that the entire field knows by one phrase: the Coin Study, the Stocking Study, and the Jam Study, " says Gilbert. "That fact tells you something important about his contributions: they are not just findings, they are memes."

What's more, Wilson is probably one of the more unassuming writers one might meet in Charlottesville. For several years in the 1990s, a reporter played senior league baseball with Wilson, and he never once mentioned what it was he did. Even for those not playing baseball, the chances are pretty good that Wilson's ideas have touched your life in some way.

"Tim is one of the most influential psychologists in the world today, and this is really not an overstatement," says UVA colleague Shigehiro Oishi. "Yet, unlike some extremely famous professors, Tim is the nicest colleague anyone can ever imagine to have. He routinely volunteers to do so many administrative duties; he volunteers to mentor junior colleagues. I can go on and on about his unselfish behaviors, which are rare in an elite institution."

Yet, as Oishi points out, in Wilson's and Gladwell's books, which have been cited from in literally thousands of publications, Wilson’s ideas about self-knowledge and unconscious mental processes have become common knowledge.

"How many scientists can claim this level of dissemination of their ideas to the public?" says Oishi. "It's truly astonishing."

According to someone closer to home, that's no accident.

"Tim lives and breathes his work with great devotion to the scientific process," says his wife, Dede Smith, a Charlottesville City Councilor.

One of their two children, Leigh, getting her masters in social work at The University of Pennsylvania, is following in her father's footsteps by focusing on evidence-based programs for at-risk populations. (Their son, Chris, a former senior editor at Slate and former editor of the Cavalier Daily, now works for Yahoo News.)

"Of course, he's not all work and no play," says Smith of professor Wilson. "For fun, we chat about what's working in Charlottesville."

I can't. Yes you can

While exposing flawed social programs and effectively dealing with trauma are two practical outcomes of Wilson's research, he also points out that his findings can be used to improve parenting skill, personal well-being, relationships, and even school performance.

For example, Wilson conducted a study with first-year college students anxious and depressed over their life's first bad grades. Many initially thought they'd been accepted to a school above their talent level, that they should transfer or quit. Had they sought counseling, the students might have been asked to delve into their academic histories, explore their anxious feelings, and try to find ways to reduce stress.

But Wilson simply asked them to fill out a survey on first-year college life. But, beforehand, he showed them the results of a similar survey that had been taken by upper-class students– so they would have an idea what the survey was like, he told them. However, the upper-class surveys were loaded with results showing that many had struggled their first year and then performed better. Wilson also threw in some hard data from previous studies he'd done, like the fact that "67 percent of the students said their freshman grades were lower than they had anticipated." In addition, Wilson had the students watch video interviews with four upper-class students who told stories about how they improved their grades each year after dismal grades the first year.

As Wilson points out, the students didn't realize that the study was designed to improve their academic performance, but when compared with a control group, who did not get such a "story prompting" session, they got better grades the following year and were less likely to drop out.

"We found that redirecting your story becomes self sustaining," says Wilson, "just from a 30-minute story-prompting session like this."

Do good, be good

The kind of narratives we create for ourselves also work in mysterious ways, Wilson shows. For example, a study asked a group of happily married people to write about how they met each other. But another group of happy couples was asked to write a story in which they imagined what their life would be like if they had never met their spouse, something Wilson and his colleagues call the "George Bailey" technique after the movie It's a Wonderful Life, in which an angel shows George what the world would have been like without him.

Wilson notes that common sense might predict that the ones asked to dwell on how they met would feel happier. "After all," writes Wilson, "who wants to dwell on the fact that they could have easily missed the party at which they met their future husband or wife?"

However, the people in the George Bailey group, the ones who imagined not meeting their beloved spouse reported a greater feeling of happiness in their relationships than the participants who had simply re-told their love stories. Their love stories, Wilson found, became "surprising and special again, and maybe a little mysterious– the very conditions that prolong the pleasure we get from the good things in life."

But Redirect isn't all about telling ourselves better stories; it's also about doing things differently. Take volunteer work. As already mentioned, simply volunteering in one's community can more effectively reduce teen pregnancy, drug abuse, and violence than can a host of popular social and educational programs.

"One of the best ways of changing people's self-views is to change their behavior first," writes Wilson. "Involving at-risk teens in volunteer work can lead to a beneficial change in how they view themselves, fostering the sense that they are valuable members of the community who have a stake in the future, thereby reducing the likelihood that they engage in risky behaviors."

It's what Wilson refers to in Redirect as the "do good, be good" principle, though he acknowledges that it is really nothing new. Indeed, as Aristotle wrote in The Politics: "It makes no small difference what habits we develop. Rather, it makes all the difference."

But in an age when talking about problems as a way of fixing them has become the norm, the notion that changing behavior first remains a radical one.

Take that, Mr Freud!

Ironically, Wilson's research in the mid-1970s is largely responsible for popularizing Freud's work on the unconscious, as it showed how unconscious mental processes informed behavior. Prior to that, Freud's work was widely thought of as nonsense. Today, the unconscious is widely accepted as a legitimate behavioral motivator, and countless people have sat on therapist couches delving into their psyches for answers to their problems.

In fact, Wilson acknowledges psychoanalysis is very useful for treating people with severe psychological problems. Indeed, the "narratives" that some people tell themselves can go completely haywire, from the intelligent serial killer who has a logical reason for chopping his victim up in to bits, or the victim of bipolar disorder who imagines he has multiple personalities and communicates with angels.

However, while Wilson acknowledges the power of the unconscious, he questions the usefulness of probing around in there for definitive answers.

As Gilbert puts it, at the center of Wilson's work "lies a single enigmatic insight: we seem to know less about the worlds inside our heads than about the world our heads are inside."

In Wilson's previous book, Strangers to Ourselves, he took aim at the popular notion that we can understand and master our psyche. Instead, Wilson revealed the ways in which we are guided by a mishmash of subconscious impulses and immediate emotions that we don't always understand.

Self-understanding, according to Wilson, has some severe limitations, a notion contrary to decades of self-help advice, psychotherapy, and various theories of enlightenment.

"There is no direct pipeline to the adaptive unconscious," Wilson declared in Strangers.

The trick, Wilson seems to be saying, is realizing that we aren't stuck in our narratives, that they can be "tweaked" and "nudged" in different directions based on new information. While he admits that the story-editing approach isn't the answer to all our complex social ills, or a magic pill for those who have experienced severe trauma, like that Florida police officer, it can be a step in the right direction.

"If you're going to tell yourself a story about your life," says Wilson, "it might as well be a good one."

5 comments

Professor Wilson's work is a great contribution and I hope that we will put his theories to work right here in our community.

One has to wonder how many of these initiatives we are funding in this region that not only do not help, but do harm.

D.A.R.E. introduces children to the government's products, and then tells them not to use them, making drugs "the thing to do" if you want to be cool and rebel against the advice of grown ups (basic psychology which is fully understood by the creators of the program). D.A.R.E. has always been the number one drug pusher on children, that's why the program was created. I had never even heard of marijuana until D.A.R.E. introduced me in elementary school to this curious looking leaf, told me it could be smoked, and told me not to smoke it.

Often the charge is made in our community that money goes to nonprofits with connections to those who hold the purse strings and not necessarily to programs that work . I am excited about the possibility that Wilson's work could change that . Does anyone know of local programs that would be candidates for this type of evaluation ?

When the expected reward fails to appear, the rat keeps on pressing the button. Often, for quite a long time. Considering Color Screen Addiction in this light might not help explain why people love toting laptops and pads and phones around, but it probably does very handily explain the puzzling actions of our government bureaucrats and politicians, who keep on proposing and then doing things ... that don't actually work.

Nudging tweakers all agree,

You CAN find a fish if there's one in the sea ....

Perhaps at some point rather than belaboring the obvious, Mr. Wilson will begin focusing at least some of his research on faith healing and other "unconscious" or "subconscious" effects of unintended mirroring behavior.