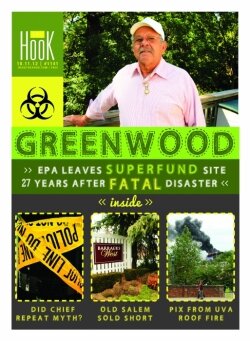

Greenwood: EPA leaves Superfund site 27 years after fatal disaster

-

hook graphic

hook graphic -

Janet Sims believes her family's health problems began when they moved to Summer Rest Lane.photo by lisa provence

Janet Sims believes her family's health problems began when they moved to Summer Rest Lane.photo by lisa provence -

The well for Mt. Zion Baptist Church, next door neighbor of Greenwood Chemical Company, is checked regularly and has a clean bill of health.photo by lisa provence

The well for Mt. Zion Baptist Church, next door neighbor of Greenwood Chemical Company, is checked regularly and has a clean bill of health.photo by lisa provence -

Charles White has lived on Newtown Road all his life, and says he's comfortable with the EPA's cleanup job at the chemical company.charles white, greenwood

Charles White has lived on Newtown Road all his life, and says he's comfortable with the EPA's cleanup job at the chemical company.charles white, greenwood -

The system that pumps, treats, and releases groundwater on the Greenwood Chemical site could be in operation for the next few decades.photo by lisa provence

The system that pumps, treats, and releases groundwater on the Greenwood Chemical site could be in operation for the next few decades.photo by lisa provence -

Newtown Elementary was a Rosenwald school, one of 5,000 funded by Sears, Roebuck president Julius Rosenwald to educate African-American children in the early 20th century.photo by lisa provence

Newtown Elementary was a Rosenwald school, one of 5,000 funded by Sears, Roebuck president Julius Rosenwald to educate African-American children in the early 20th century.photo by lisa provence -

Most of the buildings on the Greenwood Chemical site were removed, but this one remains.photo by lisa provence

Most of the buildings on the Greenwood Chemical site were removed, but this one remains.photo by lisa provence -

Another empty house on Summer Rest Lane beside the Superfund site.photo by lisa provence

Another empty house on Summer Rest Lane beside the Superfund site.photo by lisa provence

The most obvious disturbance to the bucolic setting of Mt. Zion Baptist Church is the sound of constant traffic zooming from Interstate 64. Less obvious, but way more disturbing about the location of the little country church: Its next door neighbor is Albemarle's only Superfund site, the designation the Environmental Protection Agency gives the most polluted, most toxic places in America.

Twenty-seven years after an explosion and fire killed more than half the workers at a chemical plant near the village center, there's finally some good news out of Greenwood. The federal government has handed control over the Superfund site to the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, which will manage the toxic aftermath of one of the most dangerous chapters in Albemarle County history.

You'd never know it to look at it now. A sign behind the chainlink fence on Newtown Road reads "Greenwood Chemical ground water treatment system," but it gives little hint of the disaster that took place on April 18, 1985. On that day, an explosion killed four of seven workers at what was then Greenwood Chemical Company.

'Buildings had exploded'

"It was the first time I'd seen anything as devastating," says Steven Meeks, then a reporter with a now-defunct Crozet newspaper, The Bulletin.

"I'd seen house fires," says Meeks, who's president of the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society. "But here, buildings had exploded."

Long before chemical manufacturing began in western Albemarle, Greenwood was better known for attracting millionaires like Chiswell Dabney Langhorne, who settled and built gracious estates like Mirador along what's now U.S. 250.

The cool mountain air prompted the 1894 opening of Summer Rest, a resort where working-class Richmonders could escape the heat, according to Phil James in the Crozet Gazette.

"I carried baggage and made $25 a day," recalls Charles White, 71, who worked there as a boy along with his mother. "That was good money in tips."

Construction of I-64 brought about the demise of Summer Rest in 1965, and White bought part of the property on Newtown Road across the street from the house where he was born. He says he paid $416 for two acres in the early '70s.

Down the road was Cockerille Chemical, a firm making chemicals for industrial, agricultural, pharmaceutical, and photographic processes. It was founded in 1947 by a DuPont chemist named F. O. "Neil" Cockerille.

"He smelled so bad from the chemicals," says White. "He blew himself up several times."

Fires and explosions would, unfortunately, become a recurring theme even after Cockerille Chemical became Greenwood Chemical– a change that happened in 1968, according to an EPA report.

"The plant caught on fire often, often," says White. And the plant manager would go put it out, he says, because "you couldn't put it out with water. We were on pins and needles."

White's house on Newtown Road stands about a half mile and up a hill from the plant. "You could smell the chemicals all the way up here," says White.

The chemical plant's presence was also felt at some of the fancy estates along Rockfish Gap Turnpike. Lang Gibson, 71, grandson of Gibson Girl Irene Langhorne and artist Charles Dana Gibson, grew up at Ramsay and remembers back 60 years ago. "One time our creek was bright red," he says. "Another time it was green."

Proximate toxins

Greenwood Chemical lies next to a small, historic African-American community called, like the road, Newtown. "It's a very dubious distinction for a community to have an EPA Superfund site next door– literally," Scott Peyton tells a reporter at his house on Greenwood Station Road, about two miles as the crow flies from the chemical plant.

Peyton is another Greenwood native. He grew up at Seven Oaks, the strawberry-producing estate his family sold in 1999 to music/real estate magnate Coran Capshaw.

Peyton is very much aware of Greenwood Chemical Company's cloudy history. He says Neil Cockerille lived near him on Greenwood Station Road and kept chemicals in his shed.

After the first wave of American environmental legislation in the '70s, Greenwood Chemical would be cited for "continuing to operate in a manner demonstrably to the peril of the local community," according to Peyton who mentions chemical-holding lagoons that overflowed and killed fish and livestock in Stockton Creek.

Peyton notes that most of America's Superfund sites are in rural communities, where well-paying jobs and solid information about the risks are hard to find.

"I think the people who worked there," says Peyton, "were not aware of the risks they were exposed to on a daily basis."

But it was a spill from a hot vat of the solvent toluene that started arcing and sparked the disastrous explosion, according to fire officials in an contemporary account in the Daily Progress. Volunteer firefighters from Crozet complained of eye irritation, and neighbors would report suffering fever blisters, sore throats, coughs, and sore eyes after the explosion.

"That was the crowning blow of a less than stellar history fraught with previous accidents and loss of life," says Peyton, who, like Charles White, knew the men who died.

Two years after the disaster, the EPA put Greenwood Chemical on its National Priorities List. Five hundred barrels of oozing, leaking drums of toxic chemicals were found buried on the site, according to a 1989 EPA report. Hazardous waste had been dumped into seven lagoons and unlined pits. The EPA found more than 20 hazardous substances, including arsenic, cyanide, benzene, and trichloroethylene– found in the soil– and in the groundwater.

"Chemicals worry Greenwood residents: Neighbors want firm closed," reads the April 24, 1985, Daily Progress headline. "Chemical Co. President: 'There is no basis for any fear!'" was the May 8, 1985, headline in The Bulletin.

Across the street from the plant, Greenwood Chemical Company's Al Cereghino was telling citizens assembled at the Newtown Community Center that the firm spent $1,500 to dig a well to check pollution and found no toxic chemicals. The community's fears were not assuaged.

Decades before the explosion, the Greenwood Citizens Council formed, says Peyton. The group was able to get a grant to hire its own independent environmental consultant to assess the EPA's findings and help the citizens where "100 percent" of the community depended on groundwater for its drinking water.

"We realized we had a tiger by the tail that far exceeded our ability to handle it," says Peyton, noting that the company's assertion that no contaminants traveled offsite "insulted our intelligence."

27 years later

The EPA would eventually spend in excess of $30 million cleaning up Greenwood Chemical, including the removal of contaminated soil, tearing down buildings, and carting off sludge and sediments from the disposal lagoons. The biggest ongoing project– and one that still continues– is constantly pumping out and cleaning up groundwater, and monitoring 25 wells on site as well as 12 surrounding residential wells, according to Kevin Greene, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality program manager for state Superfund sites.

On March 16, 2012, the DEQ took over full operation of the Greenwood Chemical Company site.

"It marks an evolution," says Greene.

Federal requirements stipulate that if a site meets certain criteria after 10 years of EPA operation and maintenance, it's turned over to the state, explains Greene.

It's now going to cost Virginia about $400,000 annually to maintain and repair the system that pumps out contaminated groundwater, captures it before it leaves the property, treats it by running it through granular activated carbon, and then discharges it at stream water quality, according to Greene.

"We've seen no impact to 12 residential wells around the site," says Greene. "Our primary objective is to contain the contamination. That's why we're pumping so hard to contain the plume."

Last year, more than 19 million gallons were pumped, treated, and released into streams after more than 55 pounds of contaminants were removed.

In addition to volatile organic compounds, the most worrisome contaminants, Greene says, may be carbon tetrachloride, "a probable carcinogen," which causes damage to the liver, kidney, and central nervous system.

When the EPA transferred the site in March, it noted that the property is safe for recreational and industrial uses. As for a seal of approval on its groundwater, there's no date in sight.

"I never say 'never,'" says Greene, "but there's no projected timeline. Fifteen, 20, 30 years– we'll do it as long as we need to."

Sick neighbors

"That plant used to explode all the time," remembers neighbor Janet Sims. "You'd see all these silver things in the air."

Sims was home the day of the explosion, when she watched four men engulfed in flames run from the chemical company, and she believes her family's problems began when they moved into a nearby house on Summer Rest Lane in 1967.

Both her parents died from cancer, she says, and a brother now suffers from bone cancer.

"Too many people in this neighborhood come up with disease," says Sims, 65, who has sarcoidosis, an inflammation of the lungs primarily found in African Americans and Scandanavians, and is more likely to be found in women. While no one is sure exactly what causes this immune system disease, some believe that toxins or allergens in the environment could be a cause, according to the American Lung Association.

"I had a lung transplant," says Sims, "because that was the only thing that would save my life."

She's not the only one with this little-known disease. "My son was born in that house," says Sims. "He has it." So does her cousin, who also lived in the Summer Rest house and in the community. She lists three other neighbors not related to her who died of sarcoidosis.

"[The EPA] claimed there was no danger to our health," says Sims. "I think it was. But I can't prove it. All the people up there had health problems. My whole family got something."

Would you drink it?

Six houses stand on Summer Rest Lane adjacent to the chemical site, and three are empty. A woman at one house moved there seven years ago, and says she doesn't know about anything about the Superfund site just down the road. She declined to give her name.

Across the street from the former plant, another relatively new resident who's home to meet his sons at the bus stop says he's not concerned about the water.

Nor is Connie Alexander, a member of Mt. Zion Church. She says the church gets regular reports on its water quality. Alexander has lived on Newtown Road all her life, and says she's not worried about her well because its elevation is above the chemical plant.

"That was a sad day," she says of when the fatal explosion occurred.

Charles White drinks the water. "I'm too far up the hill," he echoes what several other residents told the Hook.

White takes care of the house on Summer Rest Lane belonging to Don and Mildred Nobles, who now live in Florida. "They're trying to sell their property," says White. "People are afraid of the chemical plant."

White, too, is a Mt. Zion member, and says the church has 16 to 20 acres it would like to sell. He acknowledges its proximity to the plant is a problem.

Two miles away, Scott Peyton also drinks the water, but he's skeptical about the site being okayed for recreational purposes.

"I wouldn't care to go there and kick a soccer ball," he says. "I wouldn't want my kid there, digging in the dirt."

Observes Peyton, "You're never going to get the site clean again. Cleaner, sure."

As a realtor, he says he's regularly asked whether potential buyers in the area should be concerned, and he responds, "I can't answer that. It's not my place to speak on a technical level. I'm a lay person."

He does advise, "Any prudent buyer should do whatever due diligence they need to reach their comfort level on any property, Greenwood Chemical aside."

As the years have passed, Peyton understands that extensive work of the EPA and DEQ "has substantially allayed some of the concerns of those in the community."

He also points out that a younger generation in its 20s and 30s doesn't have the base of personal experience that he does.

"Had there not been government involvement, it would be a highly contaminated site that would continue to leach into the soil and groundwater," he says. "That being said, if I lived right next door to that chemical company, I'd be deeply concerned."

11 comments

Great article Lisa. Thank You.

thanks for the history lesson, no wonder i cant catch anything in stockton crk

Agree with the above comments. A well-researched and captivating read.

This story reminds me of the fenced-off piece of land with the light post next to the 'Virginia Blue Ridge Railway Trail' along the Piney River. Is that some sort of poisonous disaster also ?

I remember driving around that area when I first moved here in '89. The first thing that struck me as odd was seeing that all of the homes had outhouses. Does anyone remember them? I started asking questions then heard and read the stories of what happened. Thanks for the very well-written and informative update. I went to a birthday party at the community center in Greenwood a couple of winters ago and nobody except for the lady in charge of the roller skates knew any of the history. It's both fascinating and haunting.

Great story but I missed the part where the person responsible for this mess went to jail or was sued into bankruptcy?

Never mind, I found the Dept. of Justice consent decree here:

http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2000-04-13/html/00-9160.htm

concerning two of the four defendants.

Albert Cereghino agreed to pay $100,000 and Greenwood Chemical Company paid $1000 and effectively surrendered the site to the EPA in exchange for a release from civil liability for a cleanup that will wind up costing $30-$50,000,000.00+

And in a second decree two other defendants found a similar way out:

http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-1999-08-18/html/99-21366.htm

High Point Chemical Corporation, $4,000,000 (parent corporation?)

Clarence Hustrulid, $100,000

Lisa, thanks for reminding us of the background, now rusty in our memories.

As for the guy going to jail, ain't that the truth -- I recall when a man in charge of Allied Chemical (the one that killed the James with Kepone) was free and wealthy enough after to buy a second home at Wintergreen (again, this was after the scandal broke). On the other hand, if it were some poor dumb slob who got drunk and cut someone in a fight, he'd be behind bars.

Wow! And I thought it was only the mold in the rental that was making me ill in Greenwood. Another Hook link led me to the history of extreme landlord neglect at the same farm, so thanks for doing your research. My hair has been falling out a lot lately...Good Lordy, I hope the water was not contaminated. I lived on Greenwood Station Road. Thank you-

I was told by a retired ATF agent that the Piney River site was where they dumped impounded moonshine over the years. He said it's contaminated with peach brandy flavored moonshine!