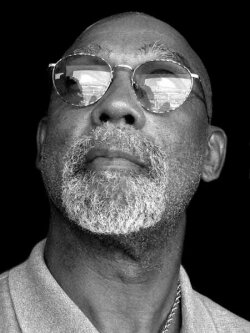

John Carlos: The silence heard round the world

When John Carlos was a seven- or eight-year-old growing up in Harlem, he had a vision of that moment on the victory stand in Mexico City at the 1968 Olympics, even down to using his left hand rather than his usual right. He imagined he was in a movie.

That premonition became an iconic image 15 years later when 200-meter bronze-medal winner Carlos and gold medalist Tommie Smith stood in front of the world and gave a Black Power salute.

"They banned us and took us off the team," recounts Carlos in a phone interview from Palm Springs High, where he's a guidance counselor. "But they never took the [U.S.] medal count down."

Carlos unsuccessfully had tried to organize a human/civil rights boycott of the '68 Olympics, demanding, among other things, that apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia be booted and Muhammad Ali's heavyweight title returned. Much has been written about the controversy the salute ignited, and Carlos found himself often portrayed in a negative light. "None of these individuals ever talked to me," he says.

That's why he decided to write his own book, The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World, because too many people asked him why he did it. "Before you could wet your lips," he says, "they're telling me why I did it."

Growing up in Harlem, Carlos encountered prominent African-American leaders like pastor and congressman Adam Clayton Powell and Malcolm X, whom Carlos would try to catch up with and talk to in between engagements. "He was a very fast walker," remembers Carlos.

He met Dr. Martin Luther King 10 days before he was murdered in Memphis, a trip about which King had his own premonition, according to Carlos. They met to discuss the Olympic boycott, and King compared it to dropping a rock in a still lake. "You're making a statement that will reach the ends of the earth with no one getting maimed or killed," Carlos says King told him.

It was from an early Olympic dream– to be the first American black swimmer– that Carlos first learned the reality of racism. "My father said, we need to talk," says Carlos. At that time, there was no way Carlos could get into a whites-only private club to train. Even at the decent public pools, whites would clear out of the water when Carlos and his friends showed up. "He was trying to express to me that I couldn't because of the color of my skin," says Carlos.

Robin Hood proved an unlikely influence on Carlos' path to the Olympics. The future medalist saw how heroin was devastating black families in Harlem and leaving hungry kids with no food in the icebox. "I saw those trains sitting at Yankee Stadium," he says, trains loaded with goods that Carlos and his band of merry men liberated and distributed– often with police hot on their heels.

His speed in eluding the heat did not go unnoticed. One day, a couple of detectives finally caught up with him, and said, "You have a talent."

"That actually was the start of my career," attests Carlos, who hadn't particularly liked track and field. "I realized God gave me a gift. It brought joy to so many people." And it led to being on that podium in Mexico City.

"John Carlos taught me that the audacity of political courage is something to value dearly, perhaps above all else," says Dave Zirin, co-writer of The John Carlos Story. "He taught me that when faced with injustice, it's always better to regret doing something than regret not doing something."

Carlos went on to tie the 100-meter world record, unofficially beat the 200-meter record, play briefly for the NFL, and earn a PhD. in humanities. At age 67, he's looking to retire in a few months.

Does one of the world's fastest men still run? He chuckles. "I still run my mouth."

Catch Carlos at the Virginia Festival of the Book's "American Icons: A conversation with the Honorable John Lewis and Dr. John Carlos," at 8pm Saturday, March 23, at the Paramount Theater. Tickets are $5.