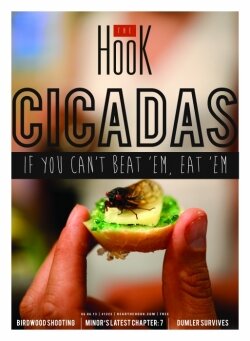

Cicadas: If you can't beat 'em, eat 'em

-

Jen Fariello

Jen Fariello -

Carlos Pezua chows down on a baguette topped with pepper jelly, cheese and the main dish: cicada.Jen Fariello

Carlos Pezua chows down on a baguette topped with pepper jelly, cheese and the main dish: cicada.Jen Fariello -

Ready, set, crunch!Jen Fariello

Ready, set, crunch!Jen Fariello -

A cicada, perhaps sensing its imminent demise, attempts to escape the mayonnaise trap before the BLT sandwich is complete.Jen Fariello

A cicada, perhaps sensing its imminent demise, attempts to escape the mayonnaise trap before the BLT sandwich is complete.Jen Fariello -

Jackson Landers and his dinner guests discuss the benefits of catching and eating one’s own food, including cicadas.Jen Fariello

Jackson Landers and his dinner guests discuss the benefits of catching and eating one’s own food, including cicadas.Jen Fariello -

Although the tomato looks tasty, the cicada can’t enjoy it. They feed only on xylem— the nutrient-rich juice in tree roots and branches.Jen Fariello

Although the tomato looks tasty, the cicada can’t enjoy it. They feed only on xylem— the nutrient-rich juice in tree roots and branches.Jen Fariello -

Landers’ children, Ida and Harry, show off their chocolate covered cicada creations.Jen Fariello

Landers’ children, Ida and Harry, show off their chocolate covered cicada creations.Jen Fariello -

Winged shrimp? Landers sautées cicadas in olive oil and Old Bay.Jen Fariello

Winged shrimp? Landers sautées cicadas in olive oil and Old Bay.Jen Fariello -

You won’t find this option in a box of Russell Stover’s, but chocolate-covered cicadas make a sweet treat for those brave enough to try.Jen Fariello

You won’t find this option in a box of Russell Stover’s, but chocolate-covered cicadas make a sweet treat for those brave enough to try.Jen Fariello -

George Emmitt

George Emmitt -

George Emmitt

George Emmitt -

Jen Fariello

Jen Fariello

Jackson Landers stands over his stove. Spatula in hand, flanked by his two eager children, he stirs the contents of the saucepan thoughtfully.

“It’s olive oil and Old Bay,” Landers says. “I was going for a traditional blue crab kind of feel.”

Crabs, however, aren’t on the menu.

Researchers’ fascination, fruit growers’ nightmare, and naturalists’ phenomenon, cicadas are now, apparently, dinner.

Landers–– renowned hunter, writer, adventurer and author of the book, Eating Aliens— is hosting a small gathering at his Scottsville home for a cicada dinner party. Though Landers himself is unsure whether the cicadas will make for a tasty meal, the excitement among the half a dozen people in his kitchen is palpable. Hopefully, the cicadas taste better than they look.

With bulging red eyes, a black head, six orange, segmented legs and translucent, orange-veined wings, a cicada seems more likely to be featured in a horror movie than on a dinner plate. But, stuffed between two pieces of golden bread, paired with fresh tomatoes, crisp lettuce and salty bacon–– or better yet, covered in melty dark chocolate–– cicadas transform from hideous creepy crawlies into a sort of strange delicacy.

For Lander’s 6-year-old son, Harry, however, the crunchy insects require no garnishing. He surveys a container of live cicadas and picks up the biggest one he can find. Without prompting, he plucks off the wings and pops the cicada in his mouth. He chews, smacking his lips. “It doesn’t have much taste," he notes thoughtfully. "It feels mushy.”

“I’m really impressed, Harry,” Landers says, asking his son if he'd like a drink to help wash it down.

Harry nods, then reconsiders. “No," he says with bravado. "Actually, I like it!”

In fact, the cicada dinner was Harry’s idea. Though several different media outlets, including the Smithsonian Magazine, reached out to Landers asking if he would do a cicada cooking event, Landers demurred because he specializes in eating invasive species. Cicadas, he notes, are native insects. It was only when his son asked if they could eat them that Landers agreed to prepare this unusual feast.

“[Harry] doesn’t have any fear about this, and there’s no reason I should give him a reason to be afraid of it," says Landers. "I’ve encouraged him to eat strange things. I mean, we’ve cooked everything from armadillo to python to frog legs to snapping turtles.”

“Don’t forget iguana!” Landers’ nine-year-old daughter, Ida, chimes in.

For the Landers family, eating unconventional foods is second nature; for this reporter, it required overcoming the voice in my head urging me to flee— and my gag reflex. Although hesitant to indulge in the cicada BLT sandwich because one of the ingredients was doing its best to crawl off the bread, when I finally took a few bites, to my shock, it was not unpleasant. The flavors blended together as usual, though I could detect a slight nutty taste and an unfamiliar crunch. Mmm protein.

“They are big, fat, juicy balls of food,” T’ai Roulston, research professor at University of Virginia and curator of the State Arboretum of Virginia says. “From dogs to pretty much all wildlife, like mice and other insects, mostly everything will eat them.”

That includes humans.

In fact, a report released this year by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organizations urges people to increase their consumption of insects to fight world hunger. Insects, which are already considered a delicacy by much of the world’s population, are “underutilized” as a food source according to the UN report. The consumption of insects including cicadas would be not only an innovative step forward in the fight against world hunger and malnutrition, but it would also help to reduce pollution and environmental degradation. Unlike livestock, insects do not require fields for grazing and they produce far less harmful greenhouses gases, such as methane, and they're high in protein and minerals. The report suggests that restaurants could do their part to overcome the insect-eating taboo by incorporating them into their menus. While the idea may yet catch on in some parts of the world, in the United States, with its fast food culture and desire for jumbo-sized servings, insects are unlikely to be featured on mainstream menus any time soon.

Though a variety of creatures dine on cicadas, the cicadas themselves feed only on the nutrients found in the roots of trees. The cicadas that have emerged this month are part of what scientists call Brood II and come out of the ground only once every 17 years. They spend about six weeks in May and June flying about and mating after spending the vast majority of their lives as nymphs, feeding underground.

Little research has been done to determine what effect the nymphal feeding on tree roots has on tree health, but most experts agree that the cicadas do cause damage to trees, especially once they emerge from the ground.

Professor of Entomology at Virginia Tech and fruit tree specialist Doug Pfeiffer says that these periodical cicadas are particularly damaging to young trees. The damage occurs when female cicadas use their pointed abdomens— called ovipositors— to make small cuts in twigs in which to lay their eggs. These cuts can cause up to 10 inches of the twig to die, and though this has no effect on mature trees’ health, for small trees it can wreak devastation.

“On a young tree, those twigs aren’t just the ends of branches; those limbs are supposed to be the main limbs of the tree when it grows up,” Pfeiffer says. “That’s why it's damaging— it’s not just that it looks bad on the end of a branch; it kills what is supposed to be the scaffold limb, or the weight-bearing limb of the tree.”

For fruit growers in the area, this is especially troublesome as a cicada emergence can mean a delay in trees’ ability to bear fruit for a year or two or sometimes longer depending on the age of the tree.

Henry Chiles, patriarch of the family-owned and operated Crown Orchards Company in Central Virginia, is one such fruit grower worried about the cicada emergence this year.

“They’re probably the worst this year that they’ve been the last three times I’ve seen them before,” Chiles says.

Though Chiles says he has increased the amount of pesticide workers spray on the trees this year, during a mid-May interview he says it's still too early to determine the extent of the damage to his trees.

“We’ll have some twig damage and some branch damage,” Chiles says, adding, “I don’t know when they’ll peak, but they’re singing pretty good today.”

Not everyone, however, believes cicadas harm trees or plants.

Crozet-based naturalist and author Marlene Condon says the idea that periodical cicadas cause damage to trees is a misperception.

“The problem for people is the appearance after the cicadas are gone of dead twig tips on woody plants," says Condon, who bases her opinion on "a lifetime of careful observation" and claims that the trees— even young ones— fare just fine.

"This is only an aesthetic problem that is not harmful to the plants," she says. "And those dead tips are extremely important to other kinds of animals like birds, who need twigs to make their nests.”

While the cicadas are considered a bounty by some and a pest by others, to a third group of people, the insects are a source of revulsion.

“I’m not a bug enthusiast, and when people said the cicadas were coming out this summer I thought they were like little grasshoppers or something,” says Jennifer Robinson, who recently moved from Crozet to Gordonsville and was horrified at the size– and volume of the cicadas. Mother to a two-and-a-half-year old, Robinson says the cicada invasion at her property took place overnight, just after Mother’s Day, and has only worsened since.

“My daughter likes to go outside and bring the dead bodies inside because she knows they scare me,” Robinson says, noting that the cicadas are concentrated in her back yard.

“All over my deck there are little dead carcasses,” Robinson says. “We spend a lot of time on the front porch now.”

In an effort to rid her deck of the cicada exoskeletons, Robinson says she arms herself with a leaf blower, takes to her deck and blasts them away, only to repeat the exercise a couple of days later when the exoskeletons build up again.

It's a Sisyphean task.

“I’ve never seen it before. They are everywhere, and they get really loud, especially near the woods,” Robinson says. “[It sounds] almost like a cement truck filled with corn kernels that just keeps turning.”

The cicadas’ song, while quieter than that of the annual cicadas, can still be overwhelmingly loud when the insects sing together in large groups known as chorusing centers. One Albemarle County resident equipped with a decibel meter measured the chorus at 80 dB—approximately as loud as a freight train 15 yards away.

It is almost impossible to estimate the number of cicadas that have emerged on the East Coast this month due to the fact that they don’t surface consistently throughout the range, or even within a single orchard. There may be thousands of cicadas on one tree and none on another just yards away, according to Pfeiffer.

Because of this uneven distribution, there is no way to know definitively how many have emerged, but Roulston says the total number of cicadas in Brood II could range anywhere from hundreds of millions to billions. He says there are pockets of highly concentrated cicada populations up and down the East Coast— Robinson's yard being one of them.

“In Virginia it is generally in the Piedmont area, east of the Blue Ridge. I’m in Shenandoah, and we don’t expect to get this brood.”

The cicadas are expected to disappear by the end of June when they have accomplished their only mission in life— mating— and their life cycle is complete. But until then, those with an adventurous streak can adopt Landers’ motto: If you can’t beat ‘em, eat ‘em.

Robinson most likely won't be joining in.

"I don’t think I could ever do that unless you put a million dollars in front of my face,” she laughs.

Those who do find sautéed cicadas appetizing can find a variety of recipes online, something Landers probably wished he had. “Next time I won’t cook them as long," he says with a laugh, looking ruefully down at a plate of the blackened bugs. But even he doesn't plan on making cicadas a regular family dinner option.

"It's not like you can open up the Joy of Cooking to a chapter on cicadas," he says.

For most people, that's probably just fine.

8 comments

Great (and disgusting) article!

Never considered eating them, although the chickens seem to like them pretty well. They're probably tired of them now.

The last time 6-year-old Harry sat down to supper at my house, I couldn't get him to try the POTATOES. But a live cicada? No problem.

I can't believe that you quote Marlene Condon as some kind of expert on the topic based solely on her naive observations of them, as though her opinion carries more weight than all the scientists who have collected and analyzed factual data for a couple hundred years.

I can.

Can we just abandon pretense and accept that the Hook is a family blog for the Jacquith/Landers family?

I hear stories by or about members of this family on NPR, too. They just happen to live here.

Hello there, I am looking for large quantities of Cicadas for exporting them to Asian countries. I am looking for people who can supply me the Cicadas.