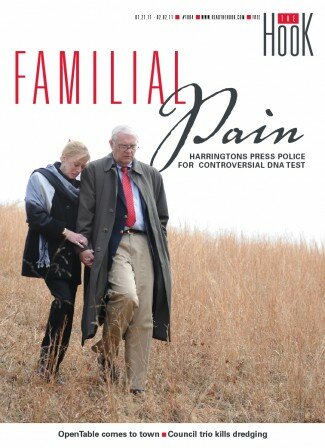

Familial pain: Harringtons press police for controversial DNA test

Dan and Gil Harrington visit the secluded spot on Anchorage Farm where their daughter Morgan's remains were discovered one year ago. PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Dan and Gil Harrington visit the secluded spot on Anchorage Farm where their daughter Morgan's remains were discovered one year ago. PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

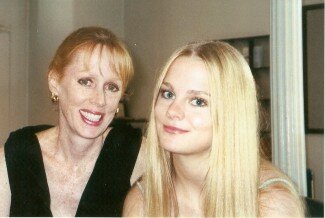

Dry grass snaps underfoot as Gil and Dan Harrington make their way across the winter-yellowed fields of Anchorage Farm, where one year ago a farmer checking fences discovered the badly decomposed remains of their daughter, Morgan Harrington. The discovery brought a tragic end to a three-month search for the 20-year-old blond beauty, who disappeared after leaving a Metallica concert at the John Paul Jones Arena.

"This is not evil land," says the bereaved mother, kneeling on the spot her daughter's body lay and touching the earth. "But there was an evil man or men here who killed my daughter."

Joined by a clutch of reporters, the parents undertook their first visit to the field, and on the walk down to the site, the 53-year-old mother clutched the arm of her husband, Dan, and cried softly amid the rolling hills nine miles south of Charlottesville.

Gil Harrington's outpouring of emotion stands in sharp contrast to the stoic frustration she expressed both in the early days of her ordeal and again in recent months as she has learned of a powerful new tool that could assist the investigation.

With police expressing their own frustration at finding a suspect, Gil Harrington has begun speaking out about the tool, which recently helped California investigators nab an alleged serial killer. It hasn't yet been used in her daughter's case–- not because there's any law preventing it, but because there's no policy regarding it at all.

"That," says Harrington, "is not an acceptable delay to use technology."

The tool she's talking about is familial DNA searching, a process by which an unidentified DNA profile–- like the one investigators have obtained in the Harrington case, which linked it to an unsolved 2005 Fairfax rape–- is run through the state's DNA databank looking not for an exact match but for a close match that would identify a family member of an unidentified perpetrator and could point in the direction of potential suspects.

The method went high profile last summer with California's so called "Grim Sleeper" case, and now law enforcement officials across the country are wondering if some of their own toughest cases might be cracked with familial DNA.

The 'Grim Sleeper' Beginning in 1985, Los Angeles detectives were stumped by a series of murders of women, many of them prostitutes, whose bodies were found in alleyways on the city's southside. After a series of expos©s by the L.A. Weekly in 2007, including an interview with the killer's only known surviving victim, police feeling the heat of public pressure ran DNA of the unidentified perpetrator (dubbed the Grim Sleeper because of an apparent 14-year hiatus in killings) through the California DNA database looking for a familial connection. After linking the killer's DNA to DNA taken from a man convicted on a felony weapons charge–- a man who turned out to be the killer's son– police homed in on 57-year-old Lonnie David Franklin Jr., and believed they'd found the killer. Franklin was arrested in July 2010 and has pleaded not guilty to 10 murder charges.

Lonnie David Franklin Jr., accused as the "Grim Sleeper," was caught with familial DNA. PHOTO BY REUTERS

Lonnie David Franklin Jr., accused as the "Grim Sleeper," was caught with familial DNA. PHOTO BY REUTERS

Only one state besides California–- Colorado–- currently uses familial DNA searching, but Virginia, a leader in the forensic use of DNA and the first state to fully fund its DNA databank in the mid-1990s, may soon follow suit, according to Gail Jaspen, chief deputy director of the Virginia Department of Forensic Science. In fact, she says, both the Attorney General's office and the Virginia Crime Commission have ruled that there's no legal obstacle preventing the state crime lab from conducting such searches and releasing results to law enforcement. The reason it hasn't already begun, she says, is that Virginia simply didn't have the necessary technology.

"We are indeed interested in acquiring the capability to do this as expeditiously as possible," says Jaspen.

That would be welcome news to the Harringtons, for whom the idea that any stone has been left unturned in the search for their daughter's killer is source of pain and fear–- fear that another woman will be killed by the same man, and another family forced to endure the agony they're suffering.

"It seems like it's getting harder now, perhaps because that protective cloaking of shock is dissipating," says Gil Harrington. "It's more apparent that she's not here, her closet doesn't smell like her anymore, we're starting to forget what her voice was like."

No named suspects The Morgan Harrington case began October 17, 2009 when a disoriented Harrington left the concert alone and began hitchhiking on the Copeley Road Bridge. During the recent media tour, the lead investigator, State Police Agent Dino Cappuzzo, told reporters that a bloodhound and eyewitness accounts confirm the area around the bridge as the last place the Virginia Tech student was spotted alive.

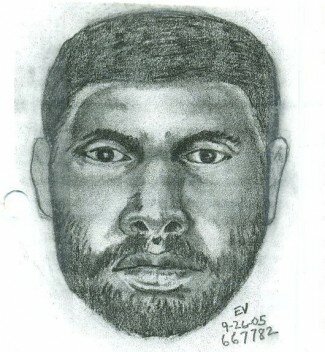

The case has stumped investigators, and a series of revelations over the past 12 months–- starting with the discovery of Morgan's body–- have provided evidence to work with but yielded no named suspects. Perhaps the most significant revelation came in July, when investigators confirmed that forensic evidence–- later confirmed to be DNA–- had linked Morgan's case to a 2005 unsolved brutal rape in Fairfax. A sketch of the suspect in the Fairfax case generated dozens of new leads, but none have led to an arrest. If Morgan's killer has a parent, sibling, or child who's been convicted of a felony since the Virginia DNA databank was launched in 1989, her parents say, there's a chance a familial DNA search could narrow the potential field of suspects in her case down from countless thousands to a few dozen.

Investigators say DNA evidence links this unknown man, responsible for a 2005 rape in Fairfax, to the Morgan Harrington case. FAIRFAX POLICE SKETCH

Investigators say DNA evidence links this unknown man, responsible for a 2005 rape in Fairfax, to the Morgan Harrington case. FAIRFAX POLICE SKETCH

The Harringtons aren't the only ones eager to see familial DNA searching become a standard weapon in Virginia law enforcement's crime-fighting arsenal–- particularly in violent crimes where a predator remains on the loose.

"A lot of times when you have a convicted felon, you'll find other felons in the family," says Albemarle County Sheriff Chip Harding, who pushed for and helped win legislation to fully fund Virginia's DNA databank back in the mid- '90s after learning that 150,000 DNA samples had been collected from felons but hadn't been entered into the databank.

Thanks to that funding, as of December 31, the Virginia DNA databank holds neary 328,000 DNA samples taken from convicted felons and those arrested for violent crimes. By the end of last year, says Harding, law enforcement officials had had 6,957 "hits"–- when DNA evidence taken from a crime scene matched a DNA profile in the databank, in many cases leading to a conviction.

Harding recalls one local case that highlighted the critical importance of the databank in solving crimes. In 1999, a man broke into a UVA student's apartment and raped her while holding her boyfriend at gunpoint. The police had no suspects, just some saliva on a beer can.

Because of a backlog of cases, it took a month for the state crime lab to finally process the DNA. And then came the "cold hit," an event Harding calls "my most exciting moment in law enforcement." The DNA from the apartment pointed to a man named Montaret Davis as responsible for the assault and paved the way to a conviction.

The validation process In late December– after lobbying by the Harringtons–- the state came one step closer to making familial DNA searches a reality as the Department of Forensic Science received and installed the familial DNA searching software used in Denver crime labs. Currently, says Jaspen, the software is going through a validation process to "ensure that it does what it's purported to do and that our people are qualified to perform the searches."

State police Special Agent Dino Cappuzzo, the lead investigator, points to the spot where Harrington's remains were found. PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

State police Special Agent Dino Cappuzzo, the lead investigator, points to the spot where Harrington's remains were found. PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

But installing software and actually using it are two different things– particularly in the Harrington case, according to State Police spokesperson Corinne Geller, who says investigators must proceed cautiously with any further DNA testing because the "amount of the evidence available is limited." (DNA evidence is destroyed when it is tested.)

Limited DNA samples aren't the only potential stumbling block for investigators. The use of familial DNA searches has already attracted the attention of the ACLU, which filed a legal challenge against California's policy of collecting DNA from arrestees (as opposed to only from convicted felons).

A July 15 editorial posted on the ACLU of Southern California's website explains the concerns about familial DNA testing.

"Whether we should expand familial searching isn’t just about the success in this case," the editorial states in the wake of the Grim Sleeper arrest. "It’s about whether familial DNA searching is really the silver bullet prosecutors suggest, and whether privacy and civil rights concerns have been adequately addressed. The answer to both questions, for the moment, is no."

And any use of familial DNA here in Virginia will receive similar scrutiny, says Kent Willis, head of the Virginia ACLU, who sees DNA profiling of any kind– particularly of those arrested but not convicted of a crime– as a possible slippery slope.

"First it was just convicted felons, then they moved to anyone arrested for a violent felony," he says of Virginia's DNA collecting policies. "We're concerned that what may happen with familial DNA testing is that once you've started the process, unless you create strict protocols, that its use will continue to be expanded and expanded." For instance, he says, "there are always calls to expand [DNA collection] to anyone arrested for felony or misdemeanor. The ultimate extension is that we should take everyone's DNA at birth."

Harding, however, scoffs at the notion that the system would be abused, and says he believes concerns about privacy issues with DNA are overblown–- and that old school investigative practices are actually far more invasive.

"I'd argue that intrusion was at its greatest in the old days, the late 70s, early 80s, when there was no such thing as DNA," he says. Harding, who worked for the Charlottesville Police Department for three decades before his 2007 election to sheriff, recalls following up on tips by digging into the alibis of anyone whose name came up in the course of the investigation–- in some cases, hundreds of people.

By contrast, he says, "If I get a list with five or six names on it from a familial DNA search– if one is extremely close, it's a really good lead– all I'm seeing is who in the family tree might meet the profile, then I put them under surveillance and take a sample."

"Taking a sample" helped Charlottesville police finally catch the Charlottesville serial rapist back in 2007. After one of Nathan Antonio Washington's victims recognized the butcher at the Barracks Road Harris Teeter as the man who'd brutalized her, police followed Washington and plucked from the trash a Burger King soda cup he'd just discarded. DNA on the straw matched the profile of the assailant who'd eluded police for nearly a decade. Washington was arrested and is currently serving four life sentences.

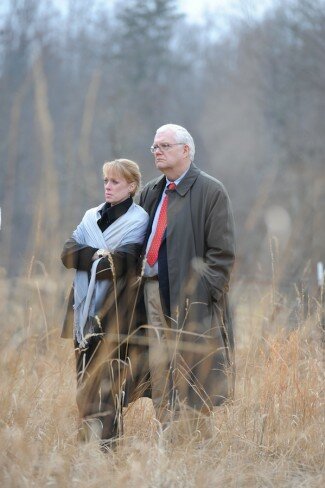

"It's striking to me how isolated this is," said Dan Harrington, surveying the secluded field where his daughter's body was found. Harrington agrees with investigators' longheld assertion that the person or people who took Morgan to Anchorage Farm know the property well and very likely remains living nearby. PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"It's striking to me how isolated this is," said Dan Harrington, surveying the secluded field where his daughter's body was found. Harrington agrees with investigators' longheld assertion that the person or people who took Morgan to Anchorage Farm know the property well and very likely remains living nearby. PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The ACLU's Willis says the capture of violent criminals like Washington– and DNA's proven ability to exonerate the wrongly convicted– make objecting to its use in criminal matters complicated. But he hopes the state will proceed with caution.

"What we want to see come out of the Virginia Crime Commission is a proposed bill that would prevent police from implementing familial DNA and would instead create a study to determine its cost, efficacy, and consider potential invasions of privacy and its impact on fairness in criminal justice system," says Willis, stressing that the ACLU is "not opposing familial DNA testing; just arguing that the state ought to move slowly into this and know exactly what it's doing and what the consequences might be."

The Harringtons, however, say moving slowly when their daughter's killer remains at large is "crazy."

"It's a tool and a technology that exists, and it should be in the hands of law enforcement in this state," says Gil Harrington. "I don't know why it would require such prodigious time."

Correction: Special Agent Dino Cappuzzo's last name is misspelled in the print edition of this story.–ed