Burned and bypassed: Rock Hill has a ghost of a garden

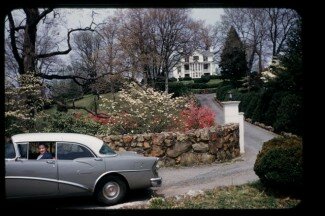

Schenk's Branch fed into a gold fish pond on the Rock Hill property before the 250 By-pass cut through.

Schenk's Branch fed into a gold fish pond on the Rock Hill property before the 250 By-pass cut through.PHOTO COURTESY DANIEL BLUESTONE

As platoons of volunteers uncover the old bones of the Rock Hill gardens, the historic Park Street estate that’s now the overgrown back yard of the Monticello Area Community Action Agency (MACAA), also unearthed has been the property's complex history as a genteel country estate, a unique experiment in landscape design, a segregation era school, and a victim of growth.

The restoration effort has been largely organized by former City Council candidate Bob Fenwick, who, along with other preservation-mined folks, wanted to draw attention to the property so that the City and the FHWA, the Federal Highway Administration, follow through on an agreement, according to a May 2010 memorandum, to restore the garden and add it to the park system as part of the new 250 interchange project.

"It's important as the home of the violin playing brother of Jefferson's master builder, James Dinsmore's, and as the home of the very capable architect Eugene Bradbury," says famed UVA architecture prof. Ed Lay. "And of course the stone-walled parterres are perhaps the only ones remaining in the city, which were used for crops and flower gardens facing the southern sun."

UVA architecture prof. Daniel Bluestone, who has been leading tours of the property, calls it among the "most complex residential garden landscapes in all of Charlottesville."

Indeed, Mary Gibbs Lane, whose father, the late Capt. John W. Gibbs bought the 8-acre property with the two-story house at auction in 1947, says there were "hundreds of amazing plants" and many different gardens. In addition, those stone parterres once surrounded the entire property, outlined the driveway and the terraced gardens which held a spring-fed lake and an island at its center.

"I remember there was a huge carved eagle with its wings spread wide on the face of the house," says Gibbs, who lived there with her father, mother, her two brothers during the 1950s. "I believe an article at the time mentioned the enormous expense and effort that Dr. Porter went to to create his amazing landscape. It was definitely not low maintenance."

Lay says the original house at Rock Hill was built in the 1820s for the Scotch-Irish Leitch family. In 1839, the Reverend James Fife, a Scotsman who became city engineer for Richmond, and was ordained a Baptist minister, purchased Rock Hill. "Former Charlottesville mayor Francis Fife descends from this Fife," says Lay.

In the 1930s, Reverend Henry Alford Porter, the minister of the Charlottesville’s First Baptist Church (Park Street), purchased the property from famed local architect Eugene Bradbury and began to create the extensive gardens.

Gibbs describes a 10 feet deep lake fed by Schenk's Branch, which at first fed into a small goldfish pond Porter had created on the upper portion of the property. On the far side of the lake, a natural waterfall flowed over a Japanese rock garden in the front corner of the property closest to McIntire Park.

Before the construction of the 250 By-pass, Gibbs described it as a "truly spectacular county property" that actually had a Rugby Avenue address. She says the by-pass construction in the late 1950s-1960s dramatically changed the site, as it cut off the Japanese garden and the front wall. Up until that time, Gibbs says her father was a "devoted steward" of Rev. Porter's creation who would hand-prune the English boxwoods, hand-spray the apple orchard, and regularly aerate the grounds with a heavy push roller with spikes.

"Dad was a retired military officer who had a passion for nature, and hard work," says Gibbs. "Believe it or not, Dad groomed and maintained the entire property by himself without a crew or yard service."

Gibbs also recalls that they kept a single cow on the property.

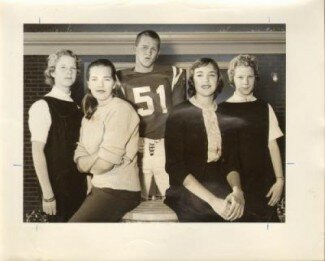

This photo of Rock Hill Academy students was taken shortly after the school opened, and includes two sets of twins. Left to Right: Rebecca Strauser, Tina Platt, Capt. James Helvin, Jr., Trevor Platt, and Diann Strauser.

This photo of Rock Hill Academy students was taken shortly after the school opened, and includes two sets of twins. Left to Right: Rebecca Strauser, Tina Platt, Capt. James Helvin, Jr., Trevor Platt, and Diann Strauser.CAHS PHOTO ARCHIVE/Rip Payne Collection

In recent weeks, former City Council candidate Fenwick has gotten assistance from a cadre of volunteers trying to bring back the skeletal remains of the parterres.

As for the missing house, Gibbs describes it as a two-story Federal built of stone and then stuccoed and painted a wheat color with dark brown trim, and later painted white with dark black-green trim. The house had 10-foot ceilings, four-hand-carved Italian marble fireplaces, and two hand-carved and curving walnut banisters. Eventually, she says, the property became too much for her father to maintain, and they ended up selling it in 1959 to a group called the Charlottesville Education Foundation.

In September 1958, after Lane High and Venable Elementary Schools were closed as part of the state's "massive resistance" movement to defy a federal order to integrate the schools, the Foundation, headed by long-time former UVA Dean Ivey F. Lewis, sought to allow people to "exercise their freedom of choice in attending sound, segregated schools "by creating a private school named Rock Hill Academy. Such schools became known as "segregation academies."

"My mother worked at the Rock Hill Academy school for over 20 years, including the transition to Heritage Christian a few decades later," says Charlottesville resident JoAnne Behrendt Kice, who points out that the school's hard line on segregation softened over the years. "My mother remembers several children of color attending the school during this period," she says.

After the sale, the main house was used as the school's administration building and contained a library in what had been the Gibbs' dining room. The house came to an inglorious end in 1963.

"Some youngster broke into it and started a fire, by accident we think," says Gibbs. "The fire did much damage to the interior of the house but left it intact enough for us to enter it and survey it–- even the second floor."

The Foundation, however, decided that restoring the house was not cost-effective.

"So the house was dismantled," says Gibbs. "We're not aware that any of it was salvaged, even the marble fire places. It was a sad day."

6 comments

I as my sisters did ,we all went to rock hill and Robert E Lee as well . we all enjoyed the days of classes taught in the gardens I remember lots of Boxwoods and lots of perennials and bulbs I being a master gardener i would love to help out on this project please feel free to get in touch with me

Need new stories! Nobody is commenting!!!!

Very interesting piece of local history, thanks Dave

Of course, I am referring to the Charlottesville churches at the end of the Civil War.

Dave, the Reverend James Fife mentioned in your article, was the first pastor of the African-American First Baptist Church, though he was white. This had to do with the formalities of forming a separate church while remaining a "sister church" to the white First Baptist Church, from whom the black congregants had requested permission to leave and form their own church. Fife was appointed to "supervise" the new church until they eventually found a black pastor, I believe. Best to check the details with the Hysterical Society.

Thanks for you hard work Bob. I have a black thumb but I hope folks like the one above can help plant Boxwoods again.