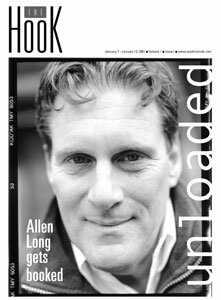

Unloaded: What a long strange trip it's been

If we told you that not too far from here, in a typical Albemarle County farmhouse on a typical small-town street, with a wife and two kids, four dogs, a spreadwing American eagle over the garage door and a basketball hoop in the driveway, there lives a guy who introduced the U. S. to Colombian gold and smuggled nearly a million pounds of it into the country from the mid-'70s to the mid-'80s, would you believe us?

Read on.

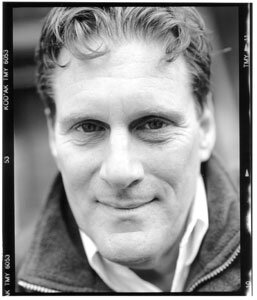

People from the Albemarle High School Class of '66 remember Allen Long. Classmates remember him as flamboyant, gregarious, even scary. "He loved attention- he still loves attention," says Wayne Coleman, one of Long's high school friends. "It was almost as if he was on stage all the time."

Long, now 53, moved to Charlottesville from Richmond at the age of 10. His mother and her new husband, revered psychology professor and runner par excellence Frank Finger, came to town when Finger joined the faculty of the University. In many ways, it was a good change for the boy. He missed seeing his namesake grandfather, a successful Richmond manufacturer. But he didn't so much miss his biological father, Jack Long, whose alleged mean streak came out in the privacy of home. In Charlottesville, his mother Eleanor Long, now Eleanor Finger, could express the love and charity he says she always felt, establishing a help-your-neighbor organization that cared for the destitute without the time-consuming paperwork of a social service agency.

Something about this combination of parentage- plus an inscrutable kernel of personality that was Allen Long's alone- sent him on adventures that not one of his three parents (nor his grandfather) could have fathomed, let alone approved. Take the charisma of Frank Finger, the entrepreneurial know-how of the elder Allen Long, the tough hide of Jack Long, the wide-open heart of Eleanor Finger. Add big doses of the thrillseeker and the perennial adolescent, and you've got Allen Long.

This is the guy who brought 972,000 pounds of pot into the country. The guy who ended up, after a decade of drug smuggling, with $25 million, then lost it all. The guy who started as a happy-go-lucky hippy, pulled together a few pot-smoking friends, cobbled together a discarded DC-3, and flew into the Colombian scrub. The guy who ended up with the muzzle of a Cuban-American thug's gun stuck in his ear, facing the choice between settling for $150,000 on a $2 million deal or having that gun blow his brains out.

Sounds like a movie, doesn't it? That's what Allen Long has thought all along. And now, with a book about his escapades coming out simultaneously in Europe and the United States, with producers lining up for movie rights, he just might see it all, bigger than life, on the silver screen.

The book is Loaded: A Misadventure on the Marijuana Trail, from the Little, Brown publishing house, and it has just hit U.S. markets. In the UK, under the title Smokescreen: A True Adventure, the book's pre-publication sales are rolling already. Even before it reached bookstores, the numbers made it a smash hit for Edinburgh-based publisher Canongate.

"We are a small independent publisher who broke the bank to secure the UK rights to Smokescreen," says Mark Stanton, publicity and marketing manager for Canongate. "Given the quality of Robert Sabbag's writing- and Allen Long's incredible story- we just had to have it. And it seems our investment will pay off. Orders for the book have exceeded our forecasts- and we will now be doing a first printing- in hardback- of 50,000 copies, far bigger than any first printing we have done before. We are excited, and confident, that we are about to have our first bestseller."

Robert Sabbag, a freelance journalist who has written for Rolling Stone, Playboy, and The New York Times Magazine, first gained fame in 1976 with Snowblind: A Brief Career in the Cocaine Trade, which Norman Mailer called one of the best books on the cocaine business. A "flat-out ballbuster" is how Hunter S. Thompson characterized it, and the New Yorker called it a "triumphant piece of reporting."

**********

Allen Long was living the high life in New York City at the peak of his smuggling career in the late '70s, when he discovered Sabbag's Snowblind.

"I was snowblind at the time," laughs Long. "I was doing coke to stay up to finish reading that book."

Not caring that it was 2am, Long found four Robert Sabbags in the Manhattan directory and called them one by one. The author was number three.

"Do you know what time it is?" asked Sabbag.

"Do you know that I have twenty $100,000 bills in my hand, ready to buy the movie rights to your book?" Long replied.

Funny thing is, Robert Sabbag tells the story differently. "He did call, but I just got a message. I don't remember just what happened- he used an old phone number or something," says Sabbag. "Anyway, people passed the message on to me. I will agree about the time of the call, though- knowing Allen, I have no doubt it was late at night."

Sabbag doesn't make much of the differences between their stories, though, and guarantees that everything recorded in Loaded went through extensive cross-referencing, both with newspaper stories of those days and with other people involved. Sabbag convinced almost everyone in Long's smuggling network to talk. "When they find out everybody else is talking, they want to tell how great they are too," he says.

"Everything that is in the book is true and corroborated," says Sabbag, convinced after research that Long's only falsehoods came to fill in gaps in his memory, particularly dates and matters of chronology. "I was astonished that he remembered so much. I had to rewrite things over and over. I had to hammer it home to Allen that you have to get these things right in a book. It has to hold up logically. Only the truth works."

Long and Sabbag do agree that their first contact came after movie rights had been sold on Snowblind. Sabbag soon went to meet Long in his New York apartment.

"My impression of him," Sabbag recalls, "was that he was a movie producer. He lived in this really expensive neighborhood, on the 35th floor of a high-rise on the Upper East Side. He was clearly quite prosperous." Those were the days now described in Loaded, when Allen Long was spending his millions, doing coke day and night, wearing thousand-dollar suits, leasing a jet year-round and tipping the pilot $10,000 at the end of each flight.

"So how did you come into so much money?" the ballsy journalist asked outright at that first meeting.

"I used to be a marijuana smuggler," Long answered, just as ballsy, and began to relate the details of his hippy-to-hoodlum escapades. By then, he was the kingpin of a smooth operation, connecting a buyer in Ann Arbor, Michigan, who always had hundreds of thousands on hand, with Miami Cubans (who toted automatic weapons and, Long claims, had CIA guardian angels watching over their every Caribbean passage) and Colombian cowboys who tended pot fields so vast they seemed like marijuana jungles.

Like any good investigative reporter, Sabbag was skeptical. Good storyteller, he thought privately. But when Long flew him down to the landing strip where two years before he had crashed his DC-3 in an effort to carry more pot than it could handle, Sabbag began to think differently. A Colombian man came out of the woods, calling out "Allen! Allen!" and thanking him profusely. He proudly led Long and Sabbag to his home, best in the village. Weather-tight and with the only windows in the whole village, it was built from the fuselage of Allen Long's crashed plane. Suddenly Sabbag believed. There was a book there worth writing.

Long was elated. But when he shared his exuberance with his business associates, the Cubans didn't crack any smiles. "That book will come out when you are dead," they said, and he believed them. Not ready to die at the age of 30, Long called Sabbag to tell him to forget the book.

"It wasn't that he used to be a drug smuggler," says Sabbag now, about those early discussions. "He was a drug smuggler." Nobody else involved would talk. For an investigative reporter determined to get at the truth, even if Long would talk, there was still no book to write."

Fast-forward 12 years from Long's first meetings with Sabbag. Long's Ann Arbor connection, arrested by the feds, had entered into a plea bargain- he and his associates, already jailed, would get short sentences in return for revealing the names of all those involved in the by-then multimillion-dollar pot smuggling ring. Long had caught wind of the scene and fled, living here and there, using several different aliases- James Edward Purcell, Kevin Thomas Burrell- names of men who had already met their maker.

"He had fallen out of touch with everybody," says Sabbag. "He was on the run, living under another name. He would call me now and then. Every six months, maybe once a year, I'd get a phone call in the middle of the night from some hotel in the Caribbean."

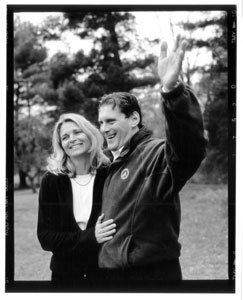

In the mid-'80s, Long found he could hide out comfortably in the islands- St. Barts, Antigua, St. Maarten- which is where he met Simone Flock, a gorgeously tall slender blonde German with her own big addiction to thrillseeking. She had just completed a trans-oceanic sailing competition, South Africa to South America, part of the only all-woman crew in the race.

She was working as a crewmember on a fast catamaran running charter trips between St. Barts and St. Maarten. Long and a date took that trip one day, but his eyes must have roamed. From that day on, Simone remembers, every time the catamaran sailed into the harbor on St. Barts, this same guy would be waving to her.

"We had every day 30 tourists on the boat," she says. "You don't pay attention to every one of them. I just had to ask, 'Who is this clown?'" Finally they talked, then started spending time together. "He was charming and fun to be with," says Simone. "I was very naÔve and very shy. I wrote to my mom and told her I had found my dream man. I was very much in love. He was my hero."

In those days, Long didn't mince words about how he made his money: he flat-out said he smuggled pot. Simone recalls her friends suspecting that he was an undercover agent, because no one that deeply involved in illegal activities talked about them so openly. If anyone argued with her about her affection for Long, she would answer, "We are in love, and I didn't do anything wrong."

Allen and Simone were married on May 2, 1987, calling New York their home. Meanwhile, the feds kept looking for him. Simone began to recognize that her new husband's life wasn't quite what she had expected. She wondered about the people who came by to talk business with him. She wondered why he had no contact with his family.

"He was a fugitive," she says, "but to be honest, Allen would never talk to anybody in front of me about those things. He would say to me, 'The less you know, the better it is for you.'"

Things got hard. There were times when she didn't know where he was. There would be separations, then surprise reunions. Simone remembers saying to Allen, "You have such a gift. I don't know why you're wasting it on this. Your mind is like a computer. You can express yourself. You're not scared."

But he was in too deep to switch careers.

When federal investigators finally tracked Long down in 1992, he and Simone and their four-year-old child were living back in St. Maarten where Long was working as a Miller beer salesman. More than 100 others involved in smuggling efforts with him had already served time.

When the feds tried to arrest him, Long tried to argue. He had quit the business. He was a married man. He was the father of a toddler. He had a reputable job. The feds said none of that mattered: he had been the leader and organizer of a major smuggling ring. He was still guilty, regardless of what had happened since.

Luckily, Long now explains, over the years he had followed the advice of one of the Miami wiseguys he knew- "one of the guys who tawks like this," Long says, lowering his voice, dumbing down his pronunciation, and holding one nostril shut to attain the perfect gangster intonation.

The rule was to hold back 20 percent as a safety fund. He had the money he needed, in other words, to fight a good fight. He hired a retired assistant U.S. district attorney, savvy in narcotics law, and came away with only a five-year sentence for passport fraud and conspiracy. The court declared that his had been a victimless crime.

For his wife, that moment represented the end of stress and worry, the end of days and weeks- even months- of wondering where her husband was. "To be honest, it was kind of a relief when he went to prison," says Simone. "For once I didn't have to worry. I knew where he was, and I knew he wasn't going to be killed."

******

Shuttling through federal penitentiaries in Tallahassee, San Juan, and Pensacola, in 1992 Long left Simone behind, alone with two small children, Matthew, 5 years, and Sean, 6 months. The family of three first went to Simone's family in Germany, then returned to Charlottesville where she squeaked by, working as a housepainter, living in an apartment owned by Allen's parents. None of them- not his wife, not either of his sons, the younger learning to walk and talk, the elder riding bikes and school buses- visited Long during the five years he was imprisoned. Long didn't want the boys to see him there. The tears still well up when Simone remembers those times. She waited until 1997, when he got out of prison, to tell Long she was divorcing him.

Long gets somber when he tells this part of the story, too. "When I got out of prison I was 47 years old," he says. "My wife was divorcing me. Anyone else would have divorced me long before that. It was a really bad time. I didn't know what to do."

He lived by himself in a little apartment on JPA. His one support was his federal probation officer, who helped Long identify his legal marketable skills.

"So what did I have?" asks Long today. "I was good at negotiating, at sales, at business management and financial management. I knew how to raise and allocate money. I could manage personnel and the books- all of which would have made me a great real estate salesman."

He flashes a big grin. "I'm an ambition-driven, greedy guy. I should have gone into real estate in the first place. Look at Frank Kessler." He pauses, thinking of the man, 10 years his elder, whom he knew in high school as the owner of a bar on the Corner and now, four decades later, as the developer of the chi-chi Glenmore subdivision. His grin turns sly. "Of course Frank Kessler will never have a book written about him."

Allen Long often goes off on tangents- more drug smuggling anecdotes, political analyses of both Bushes, recitations of the lessons he lives by- thereby dodging the hard part. But finally he gets back to the pain.

"I remembered how I felt when I was a little boy and my parents divorced," he says. "I wasn't going to let that happen to my boys. I asked my wife for another chance. She changed her mind and gave me a chance- one more chance. I'm still riding on that chance."

It took over a year for Simone to change her mind. She looked at things with practicality. "Life is hard by yourself," she says today. "Living with Allen was not always the easiest thing to do, but I knew what I had. I didn't have to figure him out. Finally, reality hits you, and you've got to look and see what you've got."

Same goes for Long. "He had a lot of time when he was in hiding and in prison," says Sabbag. "As much as he likes to revel in the memories, I think there's also a sort of remorse." Sabbag sees the publication of Loaded as an important step in Long's rehabilitation.

Long doesn't see his crime as victimless. "When I got out of jail, I had to face the truth. What really mattered wasn't the gold. It wasn't the Maserati or the Rolexes or the beach house. It was my wife and kids."

Their older son is 14 now, the time when kids invite him to join them and smoke a few Js. Their younger son, 9, sometimes needs to be reminded to smile.

What's a father (and convicted felon) to do?

For one thing, to address these wrongs, Long helps support AVARY, Alternative Ventures for At-Risk Youth, a nonprofit foundation that funds summer camp experiences for children whose parents are in prison. Joining Long in the effort are his longtime friends, surviving members of the Grateful Dead. To help in the fund- and consciousness-raising efforts of AVARY, Long offers his own family story publicly as an example of the devastating effects on children of a parent's incarceration.

When his older son was in second grade, a teacher asked him, "Do you want to end up like your father, in jail?"

Soon after Long was released, his younger son responded to a friendly bedtime story by pounding on his father in an outburst of anger.

"I managed to calm him down and asked why he was so upset," says Long.

The five-year-old answered, "Because you don't love me." Long assured the boy that of course he loved him and always had. "But you went to prison and didn't take me!" his son said, sobbing.

"The ones who really suffer are the children," says Long.

Working on AVARY may make Allen Long feel better, but it doesn't necessarily help him raise his sons. He's having to navigate the issues faced today by so many parents of teenagers, people who themselves came of age during the '60s and early '70s. How do you protect your child from making the wrong decisions, from making choices that could have irreversible legal, emotional, mental or physical consequences? How do you set rules and still avoid adolescent accusations of hypocrisy? What do you say about your own past? How do you keep communication open? "I worry about my kids all the time," Long says.

He thinks about the example of his biological father. "If he had caught me smoking pot, he would have [beat] the living tar out of me and told me I could never see those friends again," he says.

Long has actually asked these questions of his stepfather, psychologist Frank Finger, who recalls the trials he went through during Allen's decades of decadence. How did he cope? "I finally threw all the psychology out the window," he says Finger told him. In short, Allen and Simone Long have to invent the rules for themselves.

Long's first rule is "They're not going to find any drugs in my house."

His second rule for his kids, he borrowed from his grandfather: "The first offense is an accident. The second is a coincidence. The third is trouble."

He encourages his children to talk openly to him and Simone if marijuana enters their lives. The third time it happens, though, they're off to military school in Montana, Long declares. He has not only his children's well being but his own reputation to protect.

"I'm like everybody else. I've been trying to make a living and support my family," says Long, who suggests it has been a long haul, financially, in these five years since his release from prison.

"Now my family is beginning to get a little security. We'll see if I've got the moral fortitude to do it." When Long's older son's schoolmates caught wind of the upcoming book telling of his father's past as a marijuana smuggler, school officials invited Long to address the student body, to counter the "cool, man!" reactions quickly spreading through the halls.

Just to look at Allen Long- wavy brown hair, average build, firm handshake, searing eyes, winning smile- you believe that his escapades are long behind him. "Even if Allen Long wanted to be the outlaw he once was, he couldn't be," says Robert Sabbag. "He's too old."

To make it as a breadwinner, Long has in the past few years activated those skills that have always served him well- negotiating, selling, managing business, the image of a good guy willing to take some risks- and turned them legal. Starting in sales, he's now into venture capital, corporate start-ups, and the occasional dotcom. "I'm an optimist and an egomaniac," he says- "Did you notice?"- then quickly adds for the public, "said with a smile, by the way."

Long's biggest success right now is Fore America, based in Williamsburg, and, in his own words, "the world's number one golf reservation company." He had great hopes for balls.com, an all-in-one online source for brand-name balls of all sports, but it didn't pan out. He's part owner of a local restaurant (which he doesn't want named) and does some music promotion as well.

Then there's all the promise packed into Loaded.

*******

Long has just returned from being wined and dined at the gala publication events associated with the book's American publication. Sabbag has already completed one publicity tour, hawking Loaded in the nation's top hippie havens, including Berkeley, Madison, and Ann Arbor. Long and Sabbag are likely to be interviewed on television. At least a dozen television shows, from Larry King to 20/20, from David Letterman to Politically Incorrect, have called their publicist and are proposing dates in the months to come. Canongate has set up a seven-city "Smugglers Tour," matching Long and Sabbag up with Howard Marks, Europe's biggest pot smuggler, and sending them across Britain.

Movie studios have told Long's agent at William Morris that they're interested: Quentin Tarantino; John Baldecchi, producer of The Mexican; an executive with Steven Spielberg's Dreamworks; and New Line Cinema. Long has heard rumors that both Brad Pitt and Matthew McConaughey want to play him, but his agent says they're too old, and she'll find some hot new star.

Sabbag has a more tempered sense of the book's movie prospects. "Let's let the book get out there. Then we'll start trying to sell the movie rights," he says. "I think the book is going to sell the movie."

Allen Long always goes for the big one. He won't take whatever comes along. First, he wants a million-dollar movie deal, which he and Sabbag will split 50-50. Next, he wants a director who sees the story the way he does. This is no Stephen Segal action adventure. This isn't another Blow. It's a pothead's Fear and Loathing, the adventures of Cheech and Chong's supplier.

"Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid with airplanes," suggests Sabbag. Like Blow, it does tell the story of a guy whose life turns from light to dark, as he's sucked into the ugly, moneymaking, gun-toting side of the pot business, facing death at many a turn- yet both Long and Sabbag see it as a comedy.

The story begins and ends with a main character who deep down is a good guy, who survives all the dangers, the risks, the misadventures, in part because he never intended to hurt anyone, and in part because, as he likes to quote one of his best friends, he was "born with a horseshoe up his ass."

"There was always the possibility of death," Long says, "but death with honor. Death for a cause. The marijuana revolution."

Now there's a phrase we haven't heard for a while.

What a Long, strange trip it's been

Simone and Allen

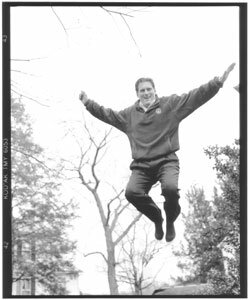

The kinder, gentler Long

The British version

The American version

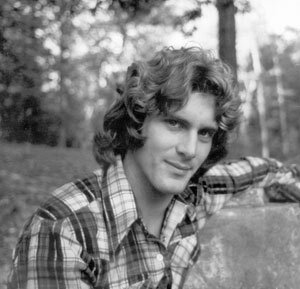

Allen Long, 1975

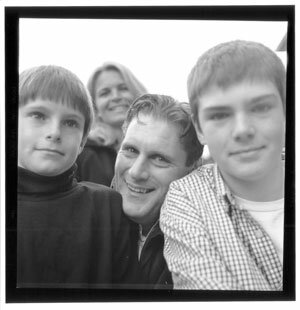

The Long family

At home in Crozet

#