Goodbye, C-ville: Anatomy of a hostile take-over

Editor's note: Tempting as it may be, this new paper will avoid self-referential reporting— except for this one time. In the interests of explaining how the Hook began, it's important to let this story be told.

It was June, 1994, when I first walked into the newspaper office looking for work. At the time, it was still called C-ville Review and published fortnightly. The office was the basement of the Jefferson Theater. Approaching owners Hawes Spencer and Bill Chapman for any open position, I was hired as the first advertising executive for the paper's jump to a weekly format.

Chapman had just returned from New York, and Rob Jiranek had just come from Chicago hoping to buy into C-ville. Almost immediately, shockwaves began to resonate. Hawes had agreed sell his majority share in the company down to a one-third stake.

"It's better," he put it to me then, "to own a little of something than a lot of nothing." He figured the two new partners could grow the business, and indeed, annual sales are now more than ten times what they were in 1994. But at what cost?

In its infancy, the C-ville Weekly was a fun place to work. Spencer's office was just a nook back by the dishwasher. The in-house reporter, art director, advertising manager, and saleswoman, Margaret, handled just about everything— including answering the phones and running up to Sylvia's for lunch for everyone.

"By hiring more ad reps, we can increase distribution to over 20,000 papers!" an exuberant Jiranek told us at our weekly staff meeting. "We can get advertisers in here from all across the state and country!" We were pumped.

"I want you to camp out on their lawn until you get a meeting with those guys!" barked Jiranek, when he insisted I gain an audience with a large local company. After a few months of persistent phone calls, I was in. Curiously, Jiranek insisted on coming along— as an "observer," he said. But when we entered the manager's office, Jiranek made an unannounced 45-minute presentation on why they should advertise in the Real Estate Weekly.

At the time, Jiranek was also publisher of that realtor-owned paper in addition to his C-ville duties. I was left with a scant five minutes to make my advertising pitch. On the drive home, I told Jiranek in no uncertain terms how I felt.

My employment was terminated not long thereafter. On my way out, I sat with Spencer, and told him he should be wary of what the left hand was doing when the right hand is busy. Spencer isn't a Buddhist and had no idea what I was talking about. He was on line two doing an interview with Greg Brady.

I moved to Seattle and for the next five years served as the grunge city's music correspondent for Rolling Stone and MTV. I forgot all about this sleepy Southern town.

Until last year. Chasing my future-bride to the altar, I returned to Virginia and to C-ville. I wrote a cover story and took over the now-departed "Cyberville" column.

Hawes lamented the perils of having two partners who fancied themselves as geniuses of mergers and acquisitions. Never mind the fact that their only foray into actually buying another paper was the ill-fated Richmond State deal. In 1996, Chapman and Jiranek convinced Spencer they could pump life into the State. However, within eight or ten weeks, Jiranek and Chapman had fired everyone and locked the doors.

C-ville fared better. Last year, while alternative papers in Baton Rouge, Iowa City, and Pittsburgh closed their doors, C-ville had another banner year— over $100,000 in profit. Publisher Chapman's financial savvy or Editor Spencer's creativity?

Whatever the cause of the paper's success, Chapman had already tired of his day-to-day role. Chapman and his wife, Shannon Worrell, had found happiness in philanthropy. They had become lead donors in local art projects including the impending construction of a new home for Live Arts and Second Street Gallery. Chapman said he wanted to focus on real estate, charity, and— to Spencer's dismay— more newspaper acquisitions.

Jiranek, meanwhile, was busy running Blue Ridge Outdoors, a publication originally conceived by two UVA students in 1995 and ran as a special supplement inside C-ville.

Despite years of effort, the B.R.O. bottom line contributed little to the parent company. Yet Jiranek wanted a raise. Around the time Spencer objected, Jiranek and Chapman had begun proceedings, through a legal loophole, to change the by-laws of their company, Portico Publications. Tossing out a rule that required three-vote unanimity, they took majority control. That happened in January, 2001. Two months later, Jiranek got his raise.

"They wouldn't fire you," I told my nervous friend. "You are the heart and soul of this paper."

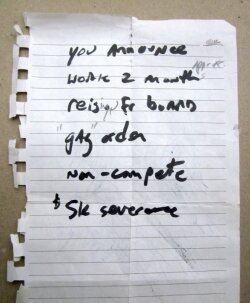

But last month, Chapman and Jiranek let the axe drop. On Monday morning, January 7, Chapman met with Spencer and handed him a scribbled list [see graphic] of demands: "you announce," "reisign fr [sic] board," "gag order," "non-compete," "5k severance."

Spencer balked. Chapman was adamant: "You have two hours to decide if you want to resign or be fired."

Spencer was in disbelief. He and Chapman had founded this paper as roommates. When Chapman went off to New York for four years, Spencer stuck it out.

"Sorry," Chapman said on his way out the door, "It's just business."

With the help of a lawyer, Spencer hung on for a week and did his job, telling no one in the office what he was facing.

"The nut of this thing is that my Portico partners wanted to take more than $100,000 of C-ville profits to expand the struggling Blue Ridge Outdoors into North Carolina," says Spencer. "That's not necessarily such a horrible idea, but they also wanted to put Chapman back on the payroll as director of mergers and acquisitions. I told them to use their own money to play publisher and to quit using C-ville as their bank."

"I wanted to resolve this," continues Spencer. "After they insisted on plundering C-ville for their schemes, I called the mediation center at Focus Women's Resource Center."

Most people know that mediation is a completely voluntary process.

"I figured," says Spencer, "the worst that might happen is they say no." How wrong he was.

Jiranek told Spencer in a meeting last month that calling the mediator, was "bad faith" and "the straw that broke the camel's back." Spencer says Jiranek also claimed that letting this reporter write for C-ville was a passive-aggressive move designed to anger his partners. Neither Jiranek nor Chapman returned phone calls seeking comment for this story.

I suppose Spencer could have taken the five grand in hush money and resigned to save face, but he didn't. It didn't help anyone's queasiness with the situation that Spencer's wife, Mary, a beloved former NBC29 news anchor, was in her ninth month of pregnancy. Many in the community were perplexed. Here's the typical refrain: "I thought Hawes owned C-ville. I thought Hawes was C-ville."

So I shouldn't have been amazed when I learned that within 48 hours of his termination Spencer had a new gig. After fielding several offers, he decided to team up with two investors including media veteran Blair Kelly, who started the Charlottesville Business Journal and Cornerstone Networks.

Chapman declined comment on Spencer in articles for Richmond's Style Weekly as well as the online industry publication, aan.org (Association of Alternative Newsweeklies). However, in a January 21 mass e-mail to some of this area's top writers, Chapman seems cordial enough. "Hawes did a great job editing C-VILLE," writes Chapman, "and we wish him the best good luck in his new endeavor (which we hear is some kind of newspaper)."

The only Jiranek comment came in a brief item in the Daily Progress:

"'There were some fundamental disagreements over the direction of the company, and Hawes in a minority position became disruptive to the direction we're trying to take our company,' Jiranek said, declining to elaborate further."

Here's an irony: Chapman and Jiranek destroyed the only non-compete clause that had existed among the trio when they re-wrote the company by-laws last year. When they fired Spencer, he was free. Free to start a whole new publication.

Take a good look at the Hook's masthead, at the byline on the cover story, and at the names of the other freelance writers in these pages. They're the core creative group from the old paper. The old C-ville is mostly gone. Everyone at the Hook had previously contributed to C-ville: the associate editor, the proofreader, the staff reporter, the copy editor, the art director, the graphic designer, the main photographer, the party photographer, the art editor, the books editor, the family editor, the music editor, the theater critic, the sports editor— even the personal ads manager, the local cartoonists, and the office manager! This is an exodus of mammoth proportions. These people didn't walk across the street and take a risk on a new publication just for a little more money.

This isn't Hawes' story after all. This is the story of a team who believed in what they were doing then, and what they are doing now, a team of creative people whose energy never died.

I told Spencer this week I thought he was fortunate to have this opportunity. Not too many people get this chance. Not too many.

#