Heartbreak: Could a simple device have saved a life?

On January 10, Madison resident Susan DeJarnette called the Hook to urge a reporter to write an article about what she described as a "critical health matter": the need for automated external defibrillators to be available in all health clubs. The equipment– which delivers an electrical shock to an irregularly beating heart– can increase a cardiac arrest victim's survival rate by as much as 85 percent, DeJarnette said.

But despite recommendations from the American Heart Association that all health clubs be equipped with such a defibrillator, commonly called an AED, her own club, Gold's Gym, did not have one at either its Charlottesville or Culpeper location. Not only that, she said, but the club had rebuffed her repeated requests to buy one.

"I don't understand why they won't get one," a frustrated DeJarnette said, pointing out that the life-saving devices cost thousands of dollars less than many of the club's exercise machines.

"All these people are in there for their New Year's resolutions, huffing and puffing," she said. "I'm just worried someone's going to have a heart attack on a treadmill and die."

On January 26, less than two weeks after her call, DeJarnette called the Hook a second time, and this time her earlier words seemed tragically prescient. Someone had suffered cardiac arrest at Gold's. And it wasn't an out-of-shape newcomer: it was her husband.

"Henry died on Sunday," DeJarnette sobbed, "on the treadmill."

Little device, big life saver

Less than 10 years ago, there was little a bystander could do to save a victim of cardiac arrest. Traditional CPR, which delivers oxygenated blood to the brain and organs, might buy some time until an ambulance arrives. But even if begun immediately, CPR alone, according the American Heart Association, saves only five percent of cardiac arrest victims.

In the early 1990s, however, the Association began recommending that AEDs be placed in public places, based on research showing that if the victim of cardiac arrest receives defibrillation, the survival rate can reach as high as 90 percent– but only if it's administered immediately after the attack.

"It's absolutely exponential," says Norman Pool, Virginia spokesperson for the Association.

In 2000, Congress signed a law allowing defibrillators to be placed in all federal government buildings, and around the same time states began signing their own AED laws into effect.

Even before defibrillators were legislated, however, some businesses jumped on the bandwagon. Major airports were among the first to install AEDs in the late 1990s, placing them both in terminals and on planes, and very quickly anecdotal evidence of the success of the device began making headlines.

One notable story involved Gary Terry, former chair of the Texas Affiliate of the American Heart Association. Terry was among the individuals who had pushed for more defibrillators in public places.

On March 19, 2001, Terry was at the Austin airport, rushing to catch an evening flight. Soon after passing through the metal detectors, Terry suffered a heart attack and collapsed. A nearby security guard administered CPR, and a bystander located an AED and administered a shock. According to an account by the National Center for Early Defibrillation, Terry made a full recovery.

The Charlottesville Albemarle Regional Airport has had AEDs on site for "a few years," says Darryl Canipe in the Aiport's public safety department, though, he adds, "We've never had to use them."

At least one local business, however, has been very glad to have an AED on site.

Local lives saved

"We've had two cardiac arrests in the last nine years," says Joe Schwar, membership coordinator and safety consultant at ACAC health club. In both cases, Schwar credits the use of AEDs– which the club has had on site for "five or six years"– for saving the members' lives.

"They're both still coming in here, working out," he says of the people saved.

Like ACAC, the Boar's Head Sports Club, the Farmington and Glenmore country clubs, and the Medfit training facility on Berkmar Drive have all had AEDs on site for "several years."

So why doesn't Gold's have a device at either location?

DeJarnette says she got an answer, but it wasn't one she wanted to hear.

In a conversation just two days after Henry's death, DeJarnette says, Gold's consultant Eddie Dail, who is overseeing the gym's upcoming move to an expanded space, approached her to offer his sympathy while she was working out at the Charlottesville club.

"He asked if there was anything he could do," DeJarnette recalls. "You could buy an AED," she says she responded.

DeJarnette and her workout partner, Jennifer Nesbit, say they were shocked by his response: that the million-dollar expansion project was a financial stretch and that purchasing an AED was "not a priority."

"He said, 'We're in this business to help people get healthy so they don't have heart attacks,'" DeJarnette says.

Dail, however, vigorously disputes her account.

"I never said that," he insists, explaining that he himself has had a heart attack, and that he's considering buying his own AED.

Although AEDs cost $3,000 to $4,000 five years ago, many of today's models today cost under $1,500.

As for why the Gold's Gyms he oversees aren't equipped with AEDs, Dail simply says, "We have a plan, and we'll continue to follow that plan to provide our members with the best workout experience possible."

Club fans

Despite her recent loss, DeJarnette agrees that the Gold's workout experience has been– and continues to be– top notch.

"The trainers there are like family to me," she says. And, she says, in many ways the club is only getting better. On March 1, the Charlottesville Gold's will move from its current location in Seminole Square to the former Food Lion space next to Kmart on Hydraulic Road, more than doubling its space from 13,000 to 27,000 square feet. Much of that space will be devoted to cardiovascular equipment–- 90 pieces in addition to a 2,500-square-foot aerobics room, a spinning room, and a mind/body room. The child-care center– designed with the idea of fighting childhood obesity– features several physical activities to keep youngsters active while their parents work out.

DeJarnette describes herself and Henry, whom she married in August 2004, as fitness buffs who worked out six days a week at either the Charlottesville or Culpeper Gold's locations. Despite his healthy lifestyle, however, 48-year-old Henry DeJarnette discovered last summer that he had a congenital heart murmur as well as a blocked artery. He had recently undergone heart surgery to implant a stent, a piece of mesh that opens a blocked artery. Even so, DeJarnette said, his doctors had cleared him for exercise, and he was in the "best shape of his life."

Thrilled by Henry's new lease on life, the DeJarnettes wanted to make sure other people getting in shape at Gold's were doing so safely.

After asking for months that the club buy an AED, DeJarnette says, she finally took matters into her own hands and bought a Philips Heartstart defibrillator for $950.

On Tuesday, January 17, two days after the device had arrived in the mail, she, Henry, and her 16-year-old son Joe took a CPR and AED training class at ACAC.

Five days later, Henry was dead.

A tragic day

Sunday, January 22 was a day like most others for the DeJarnettes. Seventeen months into their marriage, they still considered themselves newlyweds. That afternoon, they had joined Joe at the Culpeper Gold's to work out as a family.

"We were always there together," DeJarnette says.

After the pair had done 20 minutes on an elliptical machine, Henry had moved to a treadmill in front of Susan, where he jogged slowly for about five minutes. The two were joking and chatting, DeJarnette recalls, but as Henry slowed to a walk for his cool down, he suddenly fell off the back of the treadmill and collapsed on the floor.

"I thought he'd tripped," she says.

She ran to his side and immediately checked for a pulse. There was none. While a nurse who'd been exercising nearby began CPR within 10 seconds, a frantic DeJarnette remembered she'd left the new AED in the car. She raced to the locker room, retrieved her keys, ran to the parking lot, and returned with the device– which she estimates took about two minutes. Though the AED administered several shocks to Henry's heart and a rescue squad arrived in under 10 minutes, Henry never revived, and he was pronounced dead at UVA hospital.

According to the Heart Association, survival rates for patients defibrillated within three to five minutes of a heart attack are between 50 and 70 percent. If the heart is shocked within one minute of the cardiac arrest, the survival rate is 90 percent.

"I'll never know what might have happened if there'd been an AED right there," says DeJarnette, who expresses relief that she was able to use her own AED within minutes of Henry's collapse.

"If I hadn't," she says, "I would be going through some pretty hellish stuff right now."

Liability questions

Gold's is not the only local club not to purchase an AED. New Fitness for Ladies, also in Seminole Square, does not have one on site either, a fact owner Karen Carpenter attributes to the cost of outfitting each of her four Virginia clubs with an AED in addition to the necessary staff training.

That may not be the only reason a club would opt out. The website of the International Health, Racquet and Sports Club Association asks clubs to "consider" buying an automated defibrillator, but it also gives several reasons why such a purchase might not be a good idea.

"Legal analysis suggests that the required addition of this medical service to health clubs may raise the overall duty of care owed to health club members," states the site. "This would undoubtedly increase the likelihood of costly and often frivolous lawsuits."

Other reasons IHRSA gives suggesting that clubs decide against AED placement: "a high employee turnover rate" that makes it "nearly impossible to ensure that a staff member holding a valid certification to operate an AED would be on premises at all times"; and the "expense" of the equipment and staff training, which, the website states, "would ultimately raise the cost of health club memberships, resulting in fewer state residents exercising."

The American Heart Association's Pool says he disagrees that the cost would have much impact.

"Most organizations are required to have CPR training anyway," he says.

As for the claim that clubs with AEDs face greater liability, Pool says simply, "The greatest risk is if you don't have them." Virginia has "very clear" Good Samaritan laws, he explains, protecting anyone from legal action who's acting in good faith to save someone.

ACAC's Schwar agrees and says he thinks health clubs may soon be liable for not having a defibrillator on site.

"The standard of care is changing," he says. "The cost is almost minimal. There is no reason for a health club not to have one."

Minimal cost, minimal difficulty

Though most people's exposure to defibrillation comes from watching shows like ER– where doctors and nurses place paddles on a patient's chest and shout "Clear!" while the victim's body lurches dramatically on the table– advocates say that AEDs are far simpler and don't require medical expertise to use.

In fact, according to the American Heart Association and various manufacturers, the vast majority of people can learn to use an AED in just an hour, typically as part of CPR training.

That's because, as Schwar suggests, the machine does all the thinking. Placed on the chest of a person who has suffered cardiac arrest, the AED first measures any electrical activity in the heart. Based on that data, Schwar says, the AED determines whether a shock is needed and when CPR should commence. (An AED does not replace the need for CPR, and the two should be used in conjunction.) Though models vary in complexity, many AEDs actually give verbal commands about how to administer CPR. An AED will not shock a person whose heart is beating normally.

In 2004, to increase the ease of purchasing AEDs, Virginia removed a requirement that forced businesses to register an AED with the state. That same year, the federal government changed the laws enabling individuals to purchase an AED directly from a distributor without a doctor's referral. Federal law still requires businesses or government agencies planning to install one to obtain a "prescription" from a physician, who then ensures that employees are properly trained and that the equipment is maintained.

How do we stack up?

Some states are already enforcing the use of AEDs in rigorous ways. Many require AEDs to be present in schools, and at least two– Arkansas and Oregon– mandate their presence in health clubs.

But aside from including AEDs under Good Samaritan laws, Virginia has done little to legislate their use, though various localities have made the purchase and placement of the devices a priority. Albemarle County has placed AEDs in government buildings and high schools, as well as in every police car. Charlottesville, however, has fewer AEDs in public places.

Smith and Crow pools, Washington Park, and Onesty Pool have AEDs, says City spokesman Ric Barrick, and an AED will soon be purchased for the Carver Recreation Center and for Charlottesville High School. In addition, the police department has several, though not every car is equipped.

Adding more is "in our strategic plan," says Barrick, "but it's not mandated."

DeJarnette says she'd like to see an AED accessible within five minutes of any public gathering place, as the Heart Association recommends.

One local expert agrees this is a worthy goal but he points out that Charlottesville already has a leg up on more rural communities.

"Time is what's critical," says Kostas Alibertis, a paramedic who works in UVA's Life Support Training Center.

"Because of Charlottesville's relatively small size," he says, emergency medical technicians can usually respond quickly and administer defibrillation within the recommended timeframe. But, he stresses, AED installation is still "important for any place that has gatherings of high- or moderate-risk people."

Remembering Henry

"It sounds like a cliché," says DeJarnette's friend Nesbit, "but Henry was seriously the nicest person I've ever known. He was always ready to help you out."

On Wednesday, January 25, 168 of Henry's friends and family members arrived at the DeJarnettes' farm in Madison to remember the custom homebuilder and outdoors enthusiast who'd embraced his new roles as husband and stepfather.

"We had just gotten married there a little over a year before," says DeJarnette sadly. Though DeJarnette had been married twice previously and has two sons– 16-year-old Joe and 22-year-old Vijay– Henry had never tied the knot.

"He told me he'd never met anyone he wanted to marry before," DeJarnette recalls.

The couple had moved into the 156-acre horse farm, which had been Henry's childhood home, and– after Henry's health problems– had spent their year focused on exercising more and eating right, DeJarnette says. Henry took no supplements other than vitamins, but he was undergoing "chelation" at the Mount Rogers Institute, a holistic treatment center. Chelation, also a controversial treatment for autism, removes heavy metals from the body, and DeJarnette says she and Henry believed it could help with heart disease.

"We were a little extreme," she says, "but we didn't do anything without a doctor's permission."

In just a year, both of their cholesterol levels had dropped by 50 points, and DeJarnette says they were leaner than either had been before.

Though they did nearly everything together– working out daily and both working from home– "We never got sick of each other," she says. "We were on a year-long honeymoon."

Now, despite her grief, DeJarnette says she's determined to move forward. She says she has no intention of suing Gold's and hopes to maintain her membership. She hopes to do what she can to get AEDs placed not only in Gold's but throughout Virginia's public spaces.

While she acknowledges Henry might not have been saved even if an AED had been closer by, she and her sons plan to push for legislation in Henry's honor requiring health clubs to keep an AED on site at all times.

The passage of such a law won't bring Henry back, but the thought of it brings her comfort nonetheless.

"It would be a really great way to remember him," she says.

Henry DeJarnette

PHOTO COURTESY SUSAN DEJARNETTE

Henry and Susan DeJarnette with sons Joseph Streaker, front, and Vijay Chokshi (cap and gown).

PHOTO COURTESY SUSAN DEJARNETTE

Henry and Susan DeJarnette worked out at both the Charlottesville Gold's Gym in Seminole Square (above) and the Culpeper Gold's. The clubs are under the same ownership, and neither is equipped with an AED.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

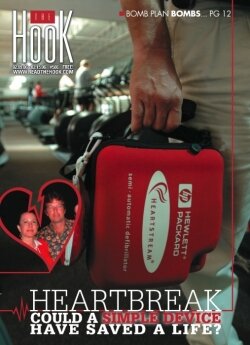

The inner workings of an AED at ACAC

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO