COVER- Unsolved: Murder on the Constitution route

Eight fatherless children. Two widows. One widower. Three grieving mothers– and three killers, presumably still walking around, never brought to justice for the three lives they took.

Albemarle County enjoys a low murder rate– two to three a year– and most of those are solved. Yet since the Albemarle Police Department was formed in 1984, three open cases linger: one as recent as last year, one in 1997, one stretching back to 1988.

(Charlottesville counts six unsolved murders since 1983 and one missing person case that was never classified as a murder.)

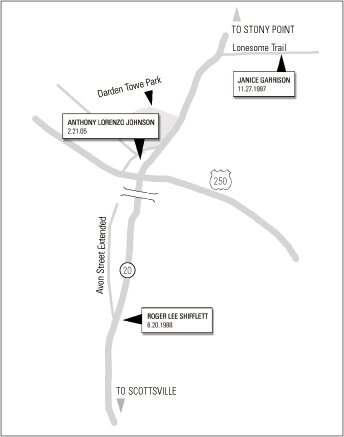

All three Albemarle slayings took place along Route 20– the Constitution Route– that stretches through Albemarle County from Scottsville to Stony Point.

These killings shook the community. Family members still grieve, denied the courtroom rituals and judgments society uses to respond to the deliberate taking of life.

"My life was never right after that," says Earl Shifflett, whose brother Roger was shot in 1988.

Worse, in at least two cases, the families– and police– believe they have a pretty good idea of who did the killing.

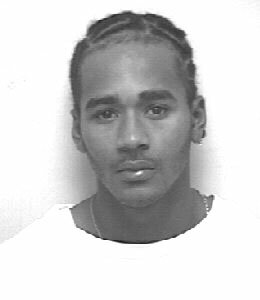

Anthony Lorenzo Johnson

Annette Scott's grief is the freshest. She's still in the year of firsts: first Christmas without him, first birthday– Anthony, her only son, was born on New Year's Eve– and first anniversary of his death.

His large extended family in Columbia called Johnson "Bunny." Like his nickname, "He was a kind-hearted person, a decent guy who never started any trouble," says his cousin, Nancy Johnson, 19. They grew up like brother and sister, and the two sisters who are their mothers live in the same neighborhood– and married two Scott brothers.

Johnson, 23, came to see his mother in Columbia "once in a blue moon," she says– but one of those visits was February 18, 2005– the Friday night before his death. He brought his girlfriend, Shaquita Ross, with whom he had lived in Charlottesville.

Annette Scott remembers him sitting around joking and laughing with her and her sister and nieces, all of whom live in the same trailer court on Ampthill Road.

"He kept getting up and going out and coming back in," recalls Scott. "He didn't seem like himself."

And perhaps Bunny did have a few things on his mind. He was living in his car, no longer in the apartment he'd shared with Shaquita and another roommate. Shaquita's 16-year-old sister, Tiara Ross, was seven months pregnant with twins, and some family members believe Bunny was the father. He had three other children with two different women.

The next night, Bunny was back in Columbia. Tiara Ross, who also would be dead two weeks later, was staying with Nancy Johnson, and he spent the night at his cousin's. "They stayed at my sister's house," rather than at his mother's, says Annette Scott. "Everyone said that seemed unusual."

Scott noticed bags of clothes in the trunk and backseat of his car, and she believes he'd been kicked out of the apartment he shared with Shaquita in Charlottesville. "He didn't have to stay in a car," she says. "I had a house. If it was about money, he could have come to me."

Scott thought Bunny was going to go to church with her that Sunday morning, but instead he left to go back to Charlottesville, says Nancy Johnson.

Bunny worked for Piedmont Concrete and was getting ready to go out of town on a job. Before Piedmont, he'd worked with his father with a construction company in Richmond.

Early Monday morning, February 21, 2005, a woman walking a dog on Free Bridge Lane near Darden Towe Park found a man's body on the ground beside a 1981 Buick Regal. Bunny had been shot once in the head.

Police say he was last seen at the nearby Pantops Amoco station around 9:30pm February 20. A videotape shows him in the parking lot, talking on a pay phone.

A year after the shooting, Albemarle police Lieutenant Greg Jenkins, expresses hope for an arrest and conviction to offer closure for the family.

"We still have leads we're following," says Jenkins. "We still believe there's a person or persons who can help us solve this. I feel confident at some point we're going to."

"Why did they do this to him?" asks Nancy Johnson. Her cousin largely avoided trouble– except for one time December 29, 2003. "He was in Charlottesville with his girlfriend, parked illegally on the side of the road," she says.

He was found guilty of carrying a concealed weapon, a misdemeanor, and received a 30-day suspended sentence.

At his funeral, "He looked like he'd been in a fight– scratches on his face, a deep cut on top of his lip," she remembers.

Family members wonder if Tiara's pregnancy caused a problem between the two sisters. Shaquita and Tiara's mother, Sharon Ross, isn't so sure that Bunny was the father of Tiara's twins.

"He said he didn't know," she says. "He said it was a possibility. I really do believe he was, but there's no way I could prove it."

They may never know. On March 3, 2005, ten days after Bunny was shot, Tiara died at home. Her mother says the cause of death was preeclampsia, a pregnancy-related form of high blood-pressure.

Shaquita Ross, 19, who lost a boyfriend and a sister, is now working to get her high school diploma in the Job Corps in West Virginia so she can study nursing, and "is still suffering," according to Sharon Ross.

"Me losing Bunny was like me losing a son I never had," she says. "They dated two years. He was always around before that. Whatever needed doing he'd do because I had no sons."

Admits Ross, "It's hard just trying to make it every day. I would feel better if they knew who did this to Bunny. He wasn't the type to bother anyone."

Annette Scott drives by Little Fork Baptist Church where her son is buried almost every morning and evening. "I always thought he'd be putting me away, not me putting him away," she says.

On Christmas, he always came sometime during the day to see his mother, but this past one, "The car never did pull up," she says. "That was the hurtin' part."

And a year later, six-year-old Tylee Johnson is still haunted by his father's death. "He had a nightmare last night," says his mother, Latoya Cooke. "He said he'd seen his daddy. 'He waved, and he said he was coming to see me,'" she quotes the youngster as saying.

Janice Garrison

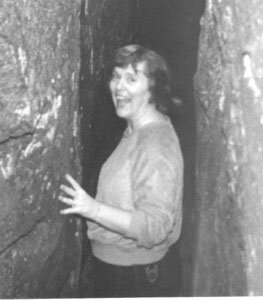

Hugh Garrison still lives in the log cabin where his wife, Janice, died in their backyard more than eight years ago.

Janice Fincham was in Lane High School when she met her future husband. Her mother babysat Hugh Garrison's baby sister. Garrison, five years older and in the service, "thought she was real sweet and a pretty girl," he says. "I asked her out, and she finally accepted." Their first date was a spaghetti dinner.

The two dated two years before they married. Janice worked as a secretary at State Farm for 30 years. She liked to collect antiques and to knit and crotchet. "She was happy, outgoing, and sincere," says Hugh Garrison. "I don't know anyone who knew her who didn't like her."

They'd been married 30 years, and Janice was 50 when she died. Her husband didn't care for the well-meaning remarks of people who said "at least she'd lived her life."

"All the women in her family," he say, "lived a long time."

It was Thanksgiving weekend. He had been out of town and had just returned to their Stony Point-area home around 4pm on November 29, 1997. From inside the cabin on their five-acre property on Lonesome Mountain Road, the couple heard gunshots in the woods.

"All this land," Garrison points out, "is posted no hunting."

He walked out towards the woods and yelled at the unseen hunters to stop shooting. "I told them I had a gun and could fire back," he says.

At that time, Garrison was a private investigator and carried a handgun. "I fired up in the air and turned around, and she was on the ground," he says. "I didn't know she was out there with me."

Lieutenant John Teixeira was the shift commander on duty that Saturday when the 4:35pm call came in. "I can see it like it was yesterday," he says. "It was a pretty sad scene– and it was pretty violent."

Janice Garrison had been shot in the head, and the shot did not come from Hugh Garrison's firearm, Teixeira says.

He's hesitant to talk about a case that's still pending, but he wants the person who shot Garrison to be brought to justice. "We're just missing that one small piece of the puzzle," he says.

Police believe they know who shot Janice Garrison, and while they decline to identify the suspect, the court records of Glen Scott Snow, 41, detail his alleged connection to the shooting.

Snow and several others were hunting in the woods near the Garrison property that day, according to court papers. Snow, who had a prior conviction for felony possession of a controlled substance, wasn't supposed to possess any firearms.

In July of the following year, Snow was indicted by a federal grand jury for being a felon in possession of a firearm the day Janice Garrison was killed. In a plea bargain, Snow produced the weapon in exchange for probation rather than incarceration. But at sentencing in June 1999, the government declined to follow through with the deal, maintaining that Snow "had failed to comply with his obligation under the plea agreement to truthfully and thoroughly cooperate."

While Snow denied any involvement in the shooting, Special Agent John Healey of the federal bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms offered testimony that alleged inconsistencies in Snow's account.

For example, one of Snow's friends informed police that when Snow returned from that day's hunting excursion, he told the friend that "rounds were whizzing by his head," according to the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals' opinion. Snow disavowed that statement.

Also, Snow's hunting partner said he'd been separated from Snow for about an hour that day, and he heard shots and saw Snow emerge from the woods in the general area where Garrison was shot.

The Hook was unable to locate Snow for comment. But his appeals attorney, Andrew Lyman Wilder, contends that his client complied with the plea agreement in "good faith," including taking multiple polygraph tests and turning over his hunting rifle.

"Short of him saying he shot the woman," says Wilder, "there was nothing he could do or say that would make the government honor the plea agreement."

Snow was sentenced June 11, 1999, to 37 months that he served at the Federal Medical Center in Lexington, Kentucky. He was released April 3, 2002.

Garrison, 63, admits that talking about the case brings up a lot of feelings he's tried to bury. "It's one of those things you can never forget about," he says. "It was devastating. I never had any closure."

He's given up days and nights sitting by the side of the road as a P.I. doing stakeouts, he says. "I had to change my lifestyle."

He now works in facilities at UVA Medical Center. And two years ago, he married Terry, who's fixing dinner as he speaks to a reporter eight and a half years after Janice's death.

"I know there are people out there who know him and know what he done," Garrison says. "They need to come forward and say something."

And while he doubts police are actively investigating the case, 'I hope someday they'll solve it, and he'll get what he deserves," Garrison says.

"The way I look at it," says Lieutenant Teixeira, "an innocent woman was killed. Someone needs to be brought to justice for it. Most cops never give up."

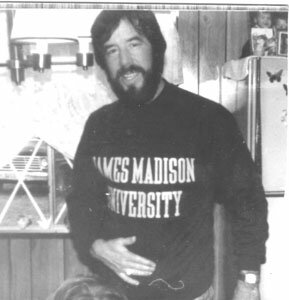

Roger Lee Shifflett

The Southwind Gas and Grocery no longer exists. The tiny stub of land near the intersection at Avon Street Extended bears no trace of the store where, almost 18 years ago, someone shot Roger Shifflett five times and left five children fatherless.

Shifflett, 38, was known as a hard-working man. He'd gone in to the store shortly after 5:30am June 20, 1988, as he usually did, to open up before going to his day job as a relief foreman with Norfolk and Southern Railroad.

A passerby later said a car like a Chevy Impala, circa the late 1960s or 1970, with a dark bottom and light top, had been parked in the lot around the time of the murder.

An employee arriving just before 6am found Shifflett bleeding on the floor. Police initially said robbery was the motive, because $135 was missing from the cash register, but as the investigation progressed, that theory changed in what is now Albemarle police's coldest case.

"We do not believe it was a random robbery and shooting," says Lieutenant Teixeira. "It was probably someone who knew or was acquainted with Mr. Shifflett."

There was no physical evidence at the scene, according to Teixeira. "We interviewed a suspect," he says. "We feel he is the person who killed Mr. Shifflett, but we didn't have enough evidence."

His family agrees that Roger Shifflett knew his killer.

His brother, Earl, was at the store that morning at 6:15am to pick up Roger to go to work at the railroad. The two brothers– two years apart in age– rode in together and worked together, and they shared similar looks.

"Albemarle County detectives told me they know who done it, but they didn't have enough evidence to prosecute," says Earl Shifflett. He says his brother was killed with his own gun that he kept in the store, and the gun was never found.

"My brother was a black belt in karate," says Shifflett, who doesn't think Roger would have been easily surprised by a stranger.

He was shot five times– in the chin, in the face, in the hip and back, says Earl Shifflett. "The last shot was execution style behind the ear," he says. "Five times– you don't shoot someone five times if you're robbing them."

Earl Shifflett believes jealousy was a motive. Roger and his wife, Barbara, were getting ready to go on vacation, a rarity for the family. Roger had confided to his brother that there had been some marital problems, but they'd been worked out.

Flowers from a flower shop on Cherry Avenue were delivered to Roger four times at the depot the week before he died, according to his brother. Earl Shifflett kept the cards and says one was signed, "Down the road, this will bring back fond memories of you."

Shifflett's family and friends offered a reward of up to $3,000 and hired a private investigator. "They told us what we already knew and charged us $10,000," says Earl Shifflett.

Jody Shifflett was 15 years old when his dad died. "It's still hard," he says. "Dad and I were close. It was not just a father-son relationship. We were getting to be friends."

Now a grown man with two sons of his own, Jody gets emotional talking about his father. "Like any other male teenager, I had my ups and downs," he says. "Dad was a major role model for me."

Jody lived with his mother during the week, and most of the weekends he spent with his dad were helping him out at the store. "I remember thinking, 'Why does Daddy work so hard?'" he says.

Roger Shifflett's oldest child, Crystal, was in college at James Madison University, and is now a teacher in Stuarts Draft. Jody works for United Parcel Service.

Roger, whom his family called "Rabbit," had remarried, and with his second wife, Barbara, he had three more boys. Twins Randy and Rodney were almost seven when he died, and the youngest, Roger Lee Jr., called Lee, was three.

Jody says he sees his stepbrothers once or twice a year. "That's one thing I do regret," he says. "It was hard for me to go back to the house. They're all good boys."

Roger Shifflett grew up in Crozet, the youngest boy in a family of 11. "We played together all the time," recalls his sister, Juanita Garrison, who was four years older than Roger, with Earl in between. "We roamed the mountains. I was a tomboy who had two boys to play with."

Her brother "worked all the time," she remembers. With 13 years in on the railroad, he'd hoped to retire early.

When Garrison learned of Roger's death, "I just remember being so upset and having a fit," she says. "We all had to go tell Mama.

"My mom always said she hoped she could live long enough to see who did it punished," adds Garrison. But Cora Frazier Shifflett died in 1997 without seeing her son's murderer brought to justice.

"He was easy going and good natured," says sister Joyce Wood. "I don't know who would want to do him that way."

Wood calls her brother's death devastating. "He was so young"– and whoever did it "is walking around scot free."

"Dad was the sort of person who never went looking for trouble," says Jody Shifflett. "But he didn't run from it. I do believe my dad knew whoever did it. The amount taken out of the store was only about $100."

Jody is incensed that no one was ever arrested. And as a UPS driver, he wonders if he's encountered his father's murderer in the course of making his deliveries.

"When does a person feel they have a right to take a person's life?" he asks. "They're taking something from everyone associated with him."

Jody's two sons, Dylan, 6, and Ryan, 3, talk about their grandfather "like they know him," says Shifflett. "That's what hurts, too."

His wish is that renewed interest in his father's death may stir someone's conscience or cause him to come forward. "There's always hope," he says. "It's good to get it out in the open. I still miss him."

Anthony Lorenzo Johnson, called Bunny by his family, died beside the Rivanna River February 21, 2005.

PHOTO COURTESY ALBEMARLE POLICE

Scene of the crime: family members think Johnson knew who killed him on the isolated Free Bridge Lane near Darden Towe Park.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Albemarle police want convictions to close these cases.

Janice Garrison on her honeymoon in 1967. "She just loved life," remembers her husband.

PHOTO COURTESY HUGH GARRISON

Hugh Garrison didn't know Janice had followed him into the yard until he turned and saw her on the ground.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Roger Shifflett, 38, worked hard to support his five children and he'd hoped to retire early from the railroad.

PHOTO COURTESY JODY SHIFFLETT

Roger Shifflett's family, including his son Jody, find it hard to understand why the surveillance camera at the Southwind Gas and Grocery on Route 20 wasn't turned on the morning a murderer came to the store.

PHOTO COURTESY JODY SHIFFLETT

SIDEBAR- Sheriff's tally: Albemarle's oldest and coldest

The Albemarle Police Department counts three unsolved murders since it was formed in 1984. But when it took over the responsibilities of the Albemarle Sheriff's Department, a couple of cases still lingered on the books.

The most grisly dates back to 1963, a hit-and-run in which a popular student may have been dragged nearly 12 miles under a sports car.

It happened in the early morning hours of March 19. Pat Akins, a 19-year-old gridiron star who had graduated from Rock Hill Academy and attended Clemson on a football scholarship, was on his way to a 3am breakfast near Mechum's River in western Albemarle County.

On rain-slicked Route 250, Akins lost control of the '62 Chevy convertible near his destination, the Tidbit Restaurant, today the site of Blue Ridge Builders Supply. His passenger was not seriously injured, but Akins was ejected from the vehicle.

A witness reported that a speeding, eastbound Triumph sports car struck Akins and sped away. The witness gave chase but the red roadster got away.

Near the intersection of Alderman and McCormick Roads in the heart of UVA, the low-slung Triumph was found around 4:30am with Akins underneath.

Police questioned the vehicle's owner, a UVA nuclear engineering graduate student named William C. Wolkenhauer. The 22-year-old Wolkenhauer claimed the car had been stolen– stolen and then returned to the UVA area. According to news reports at the time, police believed the death car had contained two passengers.

As police searched for the culprit, questions arose over the specifics of the accident. Akins' body had cuts and abrasions– but the initial autopsy suggested that Akins may have been slumped into the car's grille or over its hood. And friends wondered how Akins could fit under the car's six-inch clearance. But a later autopsy did not rule out the dragging theory.

"I'm not sure he was dead when he was struck– nor that he was dragged from Mechum's River," says former Sheriff George Bailey 43 years later. "He'd be chewed up."

What wasn't in dispute was that a popular young man was struck and killed two days after his 19th birthday. Bailey suspected the owner of the car, but says the Commonwealth's Attorney advised him against pressing charges. "There was enough to indict him," Bailey quotes the prosecutor, "but not to convict."

Efforts to reach Wolkenhauer were unsuccessful.

***

Another case with many questions and no conviction is the 1977 shooting death of Keswick Country Club golf pro Belden G. McMillen.

It happened in the parking lot of what today is Keswick Hall, a luxurious, internationally known inn and country club. The earlier Keswick incarnation was a spot with plenty of trouble, none more prominent than what happened to McMillen one fall evening.

On September 24, the club hosted a golf tournament and banquet. McMillen's wife, Mary, worked in the snack bar and pro shop. After closing the snack bar that night, McMillen, 49, walked his wife to her car, and then went to his truck, carrying a bank bag with the day's receipts.

As he sat waiting for Mary's car to warm up, someone opened the passenger door of the truck, grappled with McMillen for the bag of money, and fired a .38-caliber revolver into the golf pro's chest, according to his brother, Francis McMillen.

The parking brake to McMillen's vehicle was off, and it had rolled and hit a tree. Police found the deposit bag with $1,000 in the truck– but no weapon.

Two months later, police were still baffled. Bailey recalls that Mrs. McMillen called her son on the CB radio and said, "Daddy's been shot," before leaving the scene in search of help.

The case took a bizarre turn a few weeks later when, despite the absence of a weapon at the scene, UVA pathologist Christopher P. Crum said he could not rule out the possibility of suicide, according to a 1978 article in the now-defunct Washington Star.

Mary McMillen took two polygraphs, according to a Daily Progress account, and the following March, police arrested a 36-year-old laborer for the crime– but the charges were quickly dropped.

As in the Pat Akins case, Bailey did not have enough evidence for a conviction. "We had a lot of questions we couldn't answer," he says– questions that have remained unanswered for 29 years.

The mystery is still unsolved of how Pat Akins ended up underneath the dented red Triumph 12 miles from where it struck him.

SIDEBAR- 20 years ago: UVA's lost student never found

UVA police once had a possible murder case, but they didn't treat it as one, and it has never been solved.

It started when friends and professors noticed that they had last seen 27-year-old physiology graduate student Pat Collins on Friday, March 21, 1986.

When a UVA police officer began rifling through Collins' backpack– instead of treating his study room in Jordan Hall as a crime scene– the case took on particularly tragic aspects, according to Hook contributor Barbara Nordin.

Best known for her Fearless Consumer column, Nordin has written several major stories on the Collins case for Charlottesville publications. One of her 1997 stories took first place for investigative reporting in the Virginia Press Association contest. The story examined some of the mistakes made by the UVA P.D., which had never before dealt with a possible homicide.

For instance, university police failed to interview many of Collins' classmates and any of his Belmont neighbors, failed to send Collins' answering-machine tape to the FBI, failed to test a Kool cigarette butt and other evidence for fingerprints, and somehow lost Collins' calendar (whose current month had been ripped out, but which might have contained impressions of lost text).

For the first five years of its investigation, the UVA police department, citing never-named missing "items," insisted to Collins' grieving family and the world that the studious Eagle Scout was a walk-away.

By 1991, however, UVA Police Chief Michael Sheffield had begun calling the case an "open criminal investigation," and Nordin suspects that Sheffield changed his approach only after Collins' stepfather, a retired California police officer, filed a request under the Virginia Freedom of Information Act to see the police file.

Sheffield responded by citing Section 2.1-342 of the Code of Virginia, which shields open criminal cases from public scrutiny. Now retired, Sheffield has long insisted that the case remains open and that all leads are being pursued. As with his no-comment approach to Nordin's stories, messages left at his home answering machine earlier this week were not returned.

Nordin has a theory about the alleged crime. She believes Collins was probably killed by a scorned lover who could have planted the dead man's personal effects back at Jordan Hall.

"I suspect he was just coming out of the closet and met Mr. Goodbar," says Nordin, noting that Collins had begun frequenting Mem Gym, which was, she says, "a no-holds-barred pick-up site in the men's locker room in the '80s."

When then-Congressman Norman Mineta succeeded in prompting a state investigation of UVA's handling of the case, the San Jose Mercury News faulted the official line supporting UVA's work as "circular reasoning."

No body was ever found.

With his canoe on top of his '75 Plymouth and his two bikes inside, Pat Collins set out from San Jose for Charlottesville in December, 1985. Three months later, he was gone.

PHOTO COURTESY CLARENCE & BARBARA SHANNON

#