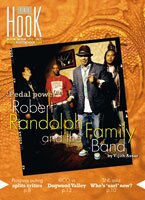

COVER- Pedal power: Can Robert Randolph 'steel' success?

Aside from his affinity for stylish hats, not much about Robert Randolph says "rock star." In fact, he didn't hear so much as a note of rock music until he was in his early twenties.

But it's his instrument that poses the biggest problem– the pedal steel guitar has all the sex appeal of a picnic table. It's a bizarre mutation of the electric guitar, with twice as many strings and often multiple necks, supported by four legs. And since one hand is working a metal slide as the other picks the strings, chord and key changes require foot pedals and knee levers, so the player has to be seated. That pretty much rules out stage diving.

The good news? The pedal steel is a rare bird in rock music, so its few practitioners stand out anyway– even when they're not stage diving.

Charlottesville is, in some ways, a surrogate home for Randolph, a relatively new client of Coran Capshaw's Red Light Management.

After getting his start playing in church in New Jersey in the 1990s, Randolph began making a name for himself when the Family Band began playing club dates in New York City. That attracted the attention of perennial rock savior Eric Clapton, but it was when the Dave Matthews Band took him under its collective wing four years ago that things really began to take off.

"We came down here and played at Starr Hill. That was the first time Coran Capshaw heard us, and I think Boyd Tinsley was at that show too," recalls Randolph.

"When I first saw Robert, what struck me was this beautiful sincerity in what he's doing," says Matthews.

That was December 2001. The following spring, DMB took them out on tour.

"We had some magical moments touring with them– we had crowds giving us a standing ovation before they came on," Randolph says. And while several DMB tour guests have been tapped for the solo spot on the band's arrangement of "All Along The Watchtower," Randolph's guest appearance at their May 29, 2002 show at Madison Square Garden is one of the standouts.

"Some people," Randolph says wryly, "think that's the best version out there." Some of those people include Dave Matthews.

More recently, the DMB connections have strengthened even further. Randolph and the Family Band are recording an as-yet-untitled album out at Haunted Hollow, DMB's ultra-private Albemarle studio. And in September the Family Band will open both DMB shows to inaugurate UVA's John Paul Jones Arena.

Matthews is even sharing his music.

"Dave had this song. He said 'Man, I've been doing this tune, but it's got you and the Family Band written all over it,'" says Randolph. So "Love Is The Only Way," with contributing vocals by Matthews, is in the works for the new album.

"All these guys had some kind of say in the next record," Randolph continues. "Dave, Boyd, Carter... they all had input."

That spirit of collaboration stretches beyond the band members; the forthcoming album includes the handiwork of multiple producers, including Mark Batson, the man who was behind the mixing board for DMB's last studio album, Stand Up.

"Not one guy steered the ship, and that's by design," says Bruce Flohr of Red Light Management. "Robert's so unique that if you get with one guy, you end up with a whole album that's exactly that."

He's right. Randolph's debut, Live at the Wetlands, did have a single pronounced theme: relatively simple jams of eight, ten, or even 13 minutes filled to the brim with just two or three chords, more technical prowess than substantive composition. Consider "Tears Of Joy," the album's closing track: "We totally just made it up on that day," admits Randolph. "That's why it goes on so long. We didn't know how to end it."

"I think the biggest issue Robert's band has is that every song sounds exactly the same," says 50-year-old pedal steel player Tony Prior. "That's why I'm not a buying fan."

"Robert has more fans than his album sales would indicate," says Flohr– insightfully, it would seem. And he has a plan for narrowing that gap: "Another thing we wanted to do," he continues, "was find Robert's voice as a singer."

The upcoming album, shared with a reporter, is slated for public release in late July. It's loaded with poppy rock- and hip-hop-influenced compositions that showcase Randolph's pipes more than ever before, pitting them against the stunning falsetto of Family Band bassist Danyel Morgan and the sultry soul of guest vocalist Leela James.

It also features more bona fide chord changes. The duet with James, for instance, is a twangy ballad ripe with the sort of harmonic games typically reserved for meticulously crafted pop-country. This in turn reveals another major switch: for the first time in Randolph's career, the album features co-writers.

While that might be a bit nerve-wracking for fans comfortable with the status quo, Flohr says he can explain the decision to bring in outside songsmiths.

"It's still true to what Robert is," he says, "It's not like we brought in Fergie from the Black Eyed Peas to sing all the songs."

"A lot of people are afraid to do co-writes," Randolph says, "because they say, 'I don't want to work with a producer or a songwriter who doesn't tour with us and doesn't know what we're about.' I tell them, 'You don't know what you're missing.' I was in a room with Rob Thomas one week, Dave Matthews one week, Kid Rock one week..."

And even with those who aren't stars yet, Randolph was getting help from the sorts of professionals typically employed by Eric Clapton, Sheryl Crow, Tim McGraw, Kenny Chesney, and Toby Keith. Add that to the producers, and you have a pretty diverse bag of... well, "influences" seems a bit too dismissive, since they all were having a direct, tangible impact on the album.

Robert, now 27, has been getting such a warm response from touring audiences for the past five years largely because of his friendly, accessible brand of funk rock– and the fact that the Family Band may just be the most monstrous rhythm section ever put behind the pedal steel.

"I think it's very innovative," says Prior. "He took the instrument that everybody kind of equates with country music and stuck it out front in a more bluesy, funky kind of atmosphere."

But it's not the first time the steel guitar has ventured past its typical stomping grounds. "Paul Franklin did it back in the '80s with Dire Straits, and David Lindley played a lap steel on Jackson Browne records," Prior continues. "It isn't the same style, but the argument came because people were saying that Robert was the first person to play rock on a steel guitar, and that's not even close to true."

Steel guitars have also been used in swing and traditional Hawaiian music. More recently, Ben Harper brought the lap steel back into the spotlight on a number of successful activist hippie rock records. Randolph is proof positive that there's more to this instrument than meets the eye.

"Robert is a challenge because he fits into so many different genres– gospel, funk, rock, jamband, and country," says Flohr, "not to mention the guy on stage– it's a party."

Indeed, Randolph seems to wear his trademark fedora just so he can fling it across the stage in convulsive improvisatory fits. His head bobs wildly, inevitably building to a full-fledged boogie attack during which his chair gets kicked away like stray cigarette butt.

"I ache a lot," says Randolph, lying atop a table in the Red Light Management conference room. "My back is killing me right now from playing shows, because I get wild and rowdy."

Will Anderson, lead vocalist for Sparky's Flaw, opened for Randolph at UVA's annual Springfest concert in April 2005, and was instantly hooked. "The steel guitar is just standing there," says Anderson, "but he's running circles around it."

Against all odds, Randolph is a remarkably engaging stage presence, and therein lies his most indisputable claim to fame: he's the first musician in history to play frontman while wielding this traditionally second-banana instrument, and he does so with enough panache to command even the most demanding spotlights. Like the Grammys, for example, where the Family Band played two months ago.

The distant melancholy of Dire Straits was an appropriate home for more traditional steel licks, but the Family Band has a groove as crushingly danceable as anybody on the market these days– in other words, not too far removed from the funky exploits of Sly and the Family Stone, to whom Randolph dedicated his tribute performance at the Grammy Awards in February.

"Not a week goes by that I don't listen to Sly and the Family Stone," says Randolph. Given the soul and funk flavors of the Family Band, that much is obvious. But some of the influences he cites are more surprising, and even further detached from pedal steel tradition: AC/DC, Aerosmith, Rage Against The Machine. Led Zeppelin.

"Zeppelin, to me, is the greatest band of all time. I get into arguments over that a lot," says Randolph, juggling a few other rock and metal favorites in the same breath. "But you can't win a battle with the Slayer kids."

The lasting legacy of the Family Band may eventually prove to be the reintroduction of a marginalized instrument to a mainstream that was inclined to ignore it– or forget about it outright, depending on who you ask.

"Randolph brings it to a whole new audience that doesn't even know what it is," says Charlotte-based pedal steeler Joe Smith. "I've played gigs where people think it's a keyboard."

Nevertheless, the reception from other pedal steel players is not always so warm. Many seem to be thrilled about the exposure he's giving the instrument, but there are also those who want to see it represented by music more typical of its Americana roots.

"There are a lot of idiots who will say, 'He's not playing country, I won't even listen to that,'" says Prior. "That's just ignorance."

"A lot of those guys in Nashville hate my guts," says an emphatically disappointed Randolph. "All these redneck dudes calling me every name in the book."

But that tension may help explain why Randolph has succeeded where 50 years of other players have failed. He's disconnected from the conventions of genre because he doesn't hail from the same lineage as the rest of the steel guitar world. Randolph got his start playing a unique brand of gospel called "Sacred Steel" in predominantly black churches.

"I started to get into playing pedal steel guitar when I was about 15 or 16," he recalls. "I wasn't serious about it at first. When I did get serious, I was only serious about wanting to be a really good church player, and nothing more than that."

Now, he's not only accomplished more, he's created something entirely his own. If the meaning of the pedal steel guitar changes in the next few decades, history will likely remember Randolph as the instigator. "With any instrument, it has to change," he says. "Look at Miles Davis, look at Hendrix."

Whether that will happen is anybody's guess; after all, his current success is testimony to the fact that he's still unique. But that may not be the case for long: he says he can see a growing interest in the pedal steel in the next generation of musicians, largely as a result of his work.

"There are a lot of them. I get emails all the time, so many that I can't even answer," he says. "You'll see in the next five or ten years, some wizard coming up."

Maybe so. But in the meantime, even the established artists are taking notice.

"I was listening to the sacred steel stuff before Robert hit," says Derek Trucks, himself a revered bottleneck slide player with the Allman Brothers Band. "It's nice to see a younger guy."

There's a local analogue to this, too: about a decade ago, the Dave Matthews Band brought the electric violin to mainstream rock audiences. And then, two years ago, there was Sean Macklin of Yellowcard prancing around with one on the Warped tour, playing to hordes of suburban tweens.

It's April 2 in Charlottesville, and the last remaining Trucks fans are beginning to wander away after his concert at Starr Hill Music Hall. Randolph is downstairs at the bar throwing back tequila shots when he's approached by an inquisitive fan.

"Aren't you Robert Randolph?" asks the admirer.

"Who's that?" answers Randolph, stifling a small smile. "I got a little shudder when you walked in," says one of the concertgoer's disappointed friends.

How many other pedal steel players have to pull that one?

Vijith Assar is the music editor of the Hook.

Robert Randolph hammers his pedal steel guitar

PHOTO BY MITCHELL JARRETT

"All these guys had some kind of say in the next record. Dave, Boyd, Carter... they all had input."–Robert Randolph

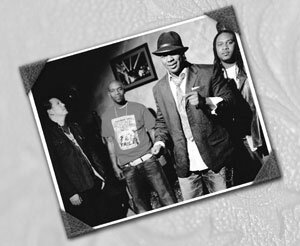

PUBLICITY PHOTO

"With any instrument, it has to change. Look at Miles Davis, look at Hendrix."–Robert Randolph

"A lot of those guys in Nashville hate my guts. All these redneck dudes calling me every name in the book. I don't pay any attention."–Robert Randolph

PHOTO BY MITCHELL JARRETT

Robert Randolph & the Family Band played two nights at Starr Hill back in 2001. They'll play here again April 20 at the Charlottesville Pavilion [There was an error in the printed version of this caption; it has been corrected in this online version.]

PHOTO BY MITCHELL JARRETT

Jason Crosby (organ and violin), Danyel Morgan (bass), Robert Randolph, and Marcus Randolph (drums)

PUBLICITY PHOTO

SIDEBAR: Big time: Robert Randolphs family affair

The Hook: You're pretty wild on stage. Were your performances at church that... enthusiastic?

Robert Randolph: No way, you can't goof off like that in church. But when the crowd is rocking, it gets good, and you just want to move. It might be a spiritual thing. It sucks because I'm sitting down playing. I'm playing a lot more regular guitar at shows, too. Sometimes I get carried away and do five straight songs on guitar, and people will be screaming, "Please, can we get the pedal steel?" And I'll be like, "No!" regular guitar is so much fun.

The Hook: Yeah, you used bona fide distorted rock guitar for the first time on "Thrill Of It." I'm also noticing overdubbed parts on "Deliver Me." I don't recall hearing that on the last few records. Is that a new thing?

Robert Randolph: No, we've done that before. That's the thing about technology today– you can do that. Sometimes you can't replace the moment of you in the studio playing it live, but if you want different flavors, you can do that. Overdubbing is kind of a thing where you get lazy. Zeppelin used to have to rehearse a tune 50 times before it was recorded. Now you can say, "Let's just put it down. Let's make it as good as we can make it, and then go back and fix it up."

The Hook: Right, but I'm talking about the parts where there are multiple steel guitar lines going on at once. Is that new?

Robert Randolph: Oh, yeah. You try to open up different doors and you hear new harmonies.

The Hook: Is "Stronger" the first time you've stepped into the traditional country role of the pedal steel guitar?

Robert Randolph: I guess so. I don't really know what traditional is. I didn't really grow up listening to that.

The Hook: Why was Leela James the right choice for that song?

Robert Randolph: You know, we had Leela James do it, but when I wrote that song, I was actually thinking about doing a collaboration with Kenny Chesney.

The Hook: How did things work with Clapton when you brought him in for your cover of the Doobie Brothers' "Jesus Is Just Alright?"

Robert Randolph: It's me and Clapton going neck and neck– like, "Let's see what you've got." "No, let's see what you've got." We rehearsed it once, twice, so it's got that energy on it and whatnot. We had toured with him and played with him so much... just backstage jamming. When I met Eric Clapton, I had to tell him, "You know, I've never really listened to a whole CD of yours, ever." It's one of those songs where you hear the whole record, and you kind of feel religious, and you kind of feel like going to party.

The Hook: Are you out to do a more vocal-oriented album here?

Robert Randolph: I write songs and come up with melodies, and sometimes I'm not even sure I can sing them. I come from a whole family of singers. Talking to Clapton and Steven Tyler, all these guys say, "Focus on the songs, and you'll have a long career." The first time you hooked up with someone, you remember what song was playing. You don't remember the solo.

The Hook: Danyel's a very capable singer.

Robert Randolph: Yeah, Danyel has been singing since he's eight, man. I've been singing since I was 22.

The Hook: So if you were having trouble, why not just pass those duties to him?

Robert Randolph: Danyel only feels comfortable singing high falsetto. Me, I don't care. He sounds great singing anything, but singing is about feeling comfortable. It's like when you see a hot girl and want to hit on her– you know you've got the words, you know you can say it, but you think you sound corny doing it.

The Hook: You make a big deal about the fact that this is a family affair. How does that affect the music?

Robert Randolph: I could get any of my other brothers or a cousin or whatever and just throw them up on stage and they'd know what to do, because that's just how we do. It's like the Detroit Pistons– they've been together for a while now, the same starting five, so they know who everybody is.

The Hook: Which of the many producers was your favorite? If you had to make an entire record with one of them.

Robert Randolph: Oh, man. You know, I don't have a favorite. To tell you the truth, I wouldn't want to make one whole record with one producer. Unless it's Rick Rubin, because he's just the man. But Mark Batson is great. We could do a whole other record with him. Tommy Sims is one of the greatest musical minds out there. He's going to be huge in the next five years. He's nuts, just on a different planet musically. It's like he can become anyone he wants. Who's that X-man that can become anyone, with the blue skin? Mystique. Yeah, that's Tommy Sims right there.

#