Wrong(ed) man: Earl Washington awarded $2.25 million

"What is one of the worst nightmares you can imagine?" Peter Neufeld asked the jury in his closing argument. "For Earl Washington, it wasn't a nightmare– it was a reality."

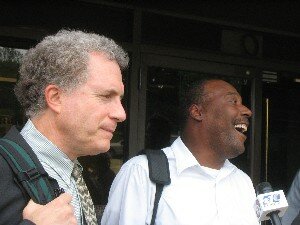

The latest chapter in this true-life nightmare brought smiles to the faces of Washington's supporters on Friday, May 5, as a Charlottesville jury awarded him $2.25 million in his civil case against the estate of the State Police investigator who obtained the confession used to convict Washington.

The state, defending the estate of Special Agent Curtis Reese Wilmore, who died in 1994, against charges that he fabricated Washington's confession, brought in a pretty big gun.

William G. Broaddus was attorney general in 1985 when Earl Washington came within nine days of being executed for a crime he didn't commit. Broaddus is now a partner at McGuire Woods.

Since his AG days, Broaddus has had a change of heart about the death penalty, and has worked with the Innocence Project, an organization founded by O.J. Simpson's former attorneys, Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld.

However, the federal courtroom in Charlottesville last week found Broaddus and Neufeld on opposite sides of the aisle. It took the jury almost six hours on May 5 to uphold Washington's claim. The legal team was suing the state rather than Wilmore's heirs because Wilmore acted as its agent in the chain of events that kept Washington imprisoned for nearly 18 years.

A happy Earl Washington never imagined he'd see this day back in 1985, when he could hear the electric chair being tested for his execution. "I was scared to death," he recalls 21 years later in the front of the federal courthouse after the jury returned its decision.

In early 1984, Washington was convicted of the June 4, 1982, rape and murder of Rebecca Williams in Culpeper. In 1993, a primitive DNA test eliminated Washington as the killer, and in early 1994 Governor Doug Wilder commuted his death penalty to life in prison.

Another DNA test in 2000 identified Kenneth Tinsley, a convicted rapist, as Williams' killer, and Governor Jim Gilmore issued Washington a full pardon in October 2000. He finally was freed on Lincoln's birthday– February 12, 2001– 18 years after he was first arrested in the case.

Both sides stipulated that Washington was innocent, and Neufeld hammered home the "overwhelming circumstantial evidence" that Wilmore fabricated evidence. That included Williams's "confession" that he had left a bloody shirt in a dresser drawer in a back bedroom in Williams' apartment.

"The bloody shirt is what caused his conviction," Neufeld told the jury.

But why would an innocent man confess to a crime he didn't commit?

The plaintiff's team brought in University of California-Irvine criminologist and false confession expert Richard Leo, who testified that juveniles or someone mildly mentally retarded, as Washington is said to be, can demonstrate compliance and be easily led in the face of police authority.

"Why would a respected law official jeopardize his reputation?" countered Broaddus in his closing argument. He pointed out that Wilmore had included in his report facts that Washington got wrong– the victim's race and location of her apartment.

And he defended the use of leading questions in an interrogation, as Wilmore's adult children, Staunton resident Todd Wilmore, and Tricia Vakos from Fredericksburg, looked on.

Broaddus called the case "tragic," but blamed it on "lies" Washington told. "He is the victim of a fabrication," said Broaddus, "but it is his own fabrication."

Broaddus and the Wilmore family exchanged an emotional hug behind the courthouse after the verdict but declined to comment.

Washington's jubilant defense team savored victory after years on the case. Robert Hall came onboard in 1985, when Washington came close to being executed and had no attorney. "For nine years," remembers Hall, "I waited to see if I'd get an invitation in the mail to his execution." Barry Weinstein has worked on the case for 15 years. And local defense attorney Steve Rosenfield was one of what Neufeld called a "ragtag of volunteers."

The case came down to two men who went into a room and came out with a confession that included nonpublished details that Washington couldn't have known, said Neufeld.

"I hope the Commonwealth takes this as a learning experience that all interrogations should be videotaped," says the attorney. If questions arise, "All an officer needs to do is press the play button." Otherwise, he warns, there will be more Earl Washingtons, and the next one may not be spared.

The attorney general's office declined comment on the verdict, but said that under current state law, individual police departments must decide whether to record interrogations. The verdict will have no effect on State Police procedures, according to spokesperson Corinne Geller.

"Our investigators already record interrogations," she says, "and have been doing it for 15 years."

Geller also declined to comment on the jury's finding that a State Police investigator fabricated a confession.

Washington turned 46 May 3. He was ready to head back home to Virginia Beach, where he lives with his wife, Pam– the couple celebrated their fourth anniversary May 4. He works as a laborer for Support Services of Virginia.

"I feel great," Washington said outside the courthouse. Its been a long time coming." #

A jury finds Earl Washington's near-death experience at the hands of the Commonwealth of Virginia worth $2.25 million. Washington, right, and his attorney Peter Neufeld are victorious outside the Charlottesville federal court May 5.

PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER  #

#