COVER- #9 dreams: Invasion of the super towers

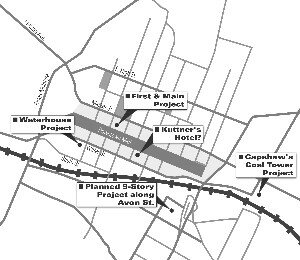

What will downtown Charlottesville look like in 20 years? If proposed nine-story building projects like Waterhouse and First & Main– not to mention a half-dozen other multi-story towers in the pipeline– are any indication, the answer is tall. Like giant spaceships landing on the Downtown Mall, these visions of the future have people both fascinated and worried.

Are they visitors from a friendly planet, or are they coming to destroy our way of life?

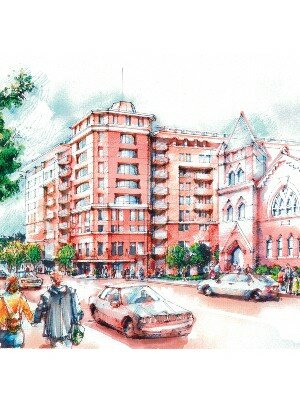

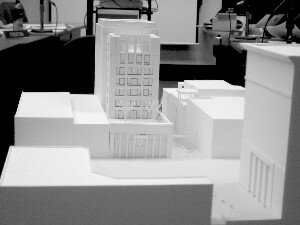

At a work session Friday, May 23 for the First & Main project, developer Keith Woodard and architect Greg Brezinski had a chance to present their nine-story project to members of the Board of Architectural Review, the Planning Commission, and the public.

Taking advantage of the City's revised zoning ordinance, passed in 2003 to encourage denser development, Woodard and Brezinski proposed a behemoth mixed-use building that will suck up nearly all the air space the ordinance allows. (Note to City: be careful what you wish for!)

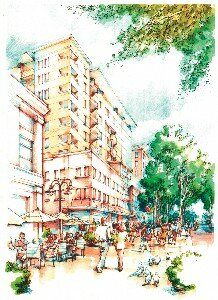

The two want to demolish everything but the facades of the buildings that Woodard currently owns between 100 and 111 East Main on the Downtown Mall and erect a nine-story retail, office, and residential structure extending to Market Street over the existing parking lot.

Three or four storefronts and the entrance to the residences would face the Mall in the former home of Antojito's bakery and Mountain Air Art Gallery. Market Street would see a fancy lobby and office space. Above it all, more office space, and above that about 70 to 80 living spaces between 980 and 2,800 square feet each. To address the parking situation, as well as avoid massive excavation for ramps, the building would include an automated underground parking system.

"Basically, it's a car elevator that stacks cars underground," says Brezinski. "You drive your car into the elevator, and when you get it back, it's turned around." Fascinating.

Unfortunately, the First & Main architecture isn't quite as interesting as Waterhouse. Although the upper floors are set back to soften the scale, and the façade tries to mimic its historic neighbors, it's basically just a massive square box. In sketches, the Market Street side resembles a hotel.

Such a structure is obviously easier (and cheaper) to build than a paragon of cutting-edge design. After all, the nearby Terraces complex (the one on the site of the old Woolworth's) took notoriously long to build and wound up running afoul of the Board of Architectural Review on several occasions.

First & Main's only noticeable contribution to the streetscape is its sheer bulk and the fact that it would bring more residents downtown. In contrast, recent renderings of the Waterhouse project present a modernist approach, juxtaposing some buildings of traditional design along South Street with a dramatic multidimensional tower soaring over Water Street.

Brezinski made an assertive presentation of the First & Main, calling it an effort to "bring people back downtown" and asking, "How do we move forward with the new downtown? What will Charlottesville look like in 30 to 40 years?"

Openly wooing his audience, he promised, "Downtown Charlottesville is going to become a cosmopolitan center, so we're really going to need your help on how to do this."

A week earlier, on May 16, the BAR had given a partial thumbs-down to Woodard's plan to clear the land by demolishing all four buildings at the site.

After a reported dozen people stood up at that meeting to ask the BAR to deny demolition of 101-111 East Main, the Board opted to compromise, voting to allow one building to be bulldozed and partial demolition of another, but calling for the complete preservation of 101 East Main, currently home to the Charlottesville Community Design Center.

Woodard had already appealed the BAR decision to City Council, which may decide at its June 5 meeting whether to enforce these recommendations. At issue are demolition requirements. Following the BAR's recommendations would make the project considerably more time-consuming and expensive. City Council will have to decide if the need for such a structure outweighs the preservation concerns.

There was some tension at the May 26 meeting. Woodward and Brezinski's presentation, seemingly a good-faith effort to maintain a dialogue with the BAR and the Planning Commission, appeared to some as merely a sales pitch, as well as a tacit acknowledgment that the BAR's decision might not be final. In fact, Brezinski began his presentation by pointing out "confusions" between the new zoning ordinance and BAR guidelines.

"As I understand it," he said, "under the BAR guidelines, if we wanted to, we could build a building eight times bigger than the Wachovia building."

Apparently, the contentious claim was based on a literal interpretation of the BAR's so-called "200 percent" rule that allows new structures to be scaled up to the "prevailing height" of nearby buildings. Meanwhile, the City's zoning ordinance caps height at nine stories and density at 87 DUA (dwelling units per acre), although 200 DUA can be allowed under special permit. BAR members admit the guidelines are confusing, but say they are meant only as guidelines.

"Don't worry," said Planning Commission member William Lucy, striking a note of calm. "We'll have plenty of time to revisit our zoning laws and guidelines if we start getting worried about too much big development."

Responding to a question about the ambitious scale of projects like First & Main, Lucy said, "Yes, we are growing, but I suppose we'd all like to advocate less dramatic transformations."

As for the building's sheer bulk, Planning Commission member John Fink wondered whether the building might eclipse the sun on the Mall. Indeed, Lee Park and everything around it could see an early sunset if the building goes up. Acknowledging that Fink had asked "a good question," Brezinski said the design team had not conducted a shadow study, but would do so in the future.

For the time being, towering developments like First & Main and Waterhouse are merely figments, their renderings and early drawings making the rounds like actors auditioning for a part in Charlottesville's future.

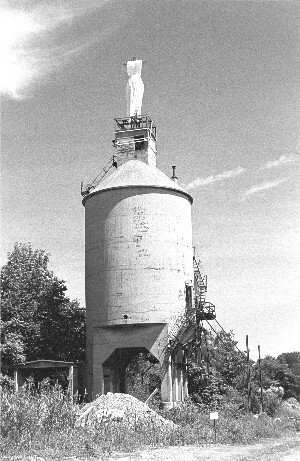

In April, city planners discussed Coran Capshaw's plan to develop the 10.8-acre site around the old CSX coal tower, a massive mixed-use complex that could include more nine-story towers.

And in May, developer Oliver Kuttner, who recently purchased the Central Fidelity/Boxer Learning building on the Downtown Mall, told the Hook ("Bad boy's back: Kuttner buys hotel building," May 11, 2006) that he hadn't ruled out the possibility of adding floors for hotel space. Former owner Lee Danielson had BAR approval to build a nine-story hotel on the site before he sold to Kuttner. "The hotel may still be a viable option," Danielson wrote in an e-mail to the Hook, "and it should be built."

At a Neighborhood Development Services meeting June 7 at City Hall, plans for yet another nine-story mixed-use building project along Avon street will be unveiled.

However, skeptics abound. J.P. Williamson, a developer of the Gleason's property on Garret Street, says flatly, "I don't think they'll get built. I don't know if the market will support them."

Williamson says that while his group, Octagon Partners, has the right to build nine stories on the south side of the former Gleason complex, cost considerations have limited the plans to 50 to 60 units in a five-story residential//retail building .

"Once you exceed five stories," he explains, "there's a whole different type of fire separation. You're in a pre-cast concrete structure."

Another developer says that shifting from "stick-built" shorter structures to "pre-cast" towers can drive construction costs as high as $275 per square foot. Including land cost, a developer might need to charge a condo-buyer $400 per square foot to make the numbers work, running the cost of a 2,500-sq.-ft. condo to nearly a million dollars. Is Charlottesville ready for that?

Already, some slightly larger units in the Holsinger– a condo tower nearing completion beside the C&O restaurant on Water Street– have sold for over a million dollars. There's one Holsinger penthouse remaining– about 2,800 square feet for $1.3 million– and the Holsinger is just five stories.

"Sometimes less is more," says commercial real estate broker Stu Rifkin. "Just because you can build it by right doesn't mean you should."

So, are there enough eager future Downtowners willing to pay $400 per square foot for the privilege of walking to the Pavilion and the Downtown Grille? If so, sooner or later one of these spaceships might get built.

And then what? What happens when they start multiplying? Are we ready to become a real mini-city– or even a city at all?

First & Main project, as seen from Market Street

A2RCI Architect Greg Brezinski's presented this rendering of the proposed First & Main project, as seen from the Mall

Developers are planning to dot the downtown landscape with nine-story buildings.

The old CSX coal tower and the 10.8 acres around it could be the site of another nine-story mixed-use building. Dave Matthews Band manager/land baron Coran Capshaw, who bought the site for $5.48 million in 2003, has plans to put up 64 townhouses, 118 condos, 2.77 acres of restaurants and retail, plus 506 new parking spaces, all while saving the tower.

Lee Danielson's plans for a nine-story hotel on the old Central Fidelity/Boxer Learning site were abandoned after he sold the building, but new owner Oliver Kuttner says it still might be a possibility

#

1 comment

I think that its great to have taller buildings downtown. It will finally make this look like a real city. If you dont like it, well you can always move! Just remember you cant stop progress!=)