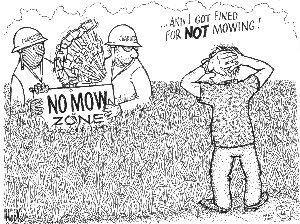

NEWS- No-mow: Near waters, City lets it grow

In 2001, a Woolen Mills resident cited by the city for growing "weeds" protested he was growing native plants as a riparian buffer. Now Charlottesville seems to be following his example by creating "no mow" zones near creeks and streams in five city parks. On April 22, Earth Day, volunteers planted nearly 250 trees in these "no-mow" zones.

"It's a relatively cost-effective way to deal with storm water run-off," notes the city's environmental administrator Crystal Riddervold, who explains that vegetation filters pollutants that otherwise might run into streams.

Though the no-mow zones appear to be a departure from city code that requires residential grass– even along streams– be kept shorter than 18 inches, Riddervold notes that the reforestation effort was called for in the 2001 revision of Charlottesville's comprehensive plan. The no-mow zones may result in a more shaggy, less manicured look on park riverbanks, but she hopes they will result in heightened awareness and more native vegetation.

"There's a strong community interest and desire to protect streams," Riddervold says.

As for houses, grass must still be mowed within 150 feet of a residence unless a citizen petitions the city to have a riparian buffer zone– and to date, no one has, says city code inspector Jerry Tomlin. "We're still enforcing [the code] as written," he says.

The city's new effort means that Azalea, Greenleaf, Jordan, Quarry, and Riverview parks are now dotted with plastic-sleeved seedlings. Some trees were planted in Azalea last year, but "This is the first formal decision to pull back on mowing," says Riddervold.

She fears "a possible misperception" that reducing maintenance was the reason. "That's not the deciding factor," says Riddervold. "We're not slacking off in maintenance."

In fact, the no-mow zones make crews more efficient, says parks and recreation department chief Mike Svetz, noting that some high-visibility areas like athletic fields or downtown's Lee and Jackson parks that may get cut twice a week can now get trimmed even more often. "We save some costs– and also reduce pollution," says Svetz.

It was Susan Pleiss, the city's outreach coordinator, who rounded up the 115 volunteers to plant and water the 10 native species, including button bush, hackberry, black locust, chestnut oak, persimmon, sycamore, and gray-stem dogwood. The trees and shrubs are Department of Forestry seedlings, mostly free, mostly in the 18-inch range. Total cost for the 250 or so new trees is around $850.

The city practices tough love with its young additions.

"They won't be watered again," says Pleiss. "They're on their own." Because the plants are small and native, unless there's a drought, Pleiss expects them to fare well.

"We don't have the labor to water these trees," she says. But the city doesn't totally abandon its young. That's where the white plastic sleeves come in.

At $1.50 each, the sleeves are about one-third the cost of the planting, but Pleiss says they can be the make-it or break-it factor in whether the trees survive against predators like rabbits and beavers. And city bush-hogging crews. "The sleeves draw attention that something is planted," Pleiss says.

With riparian buffer zones going in all over town, will the overgrowth on banks make them inaccessible?

Perhaps not. At Riverview, for instance, paths will be mown to provide access to the Rivanna River. And Pleiss says except for groupings of button bush, none of the trees are closer than 20 feet, and most are 50 feet apart.

"At Greenleaf, we put in only 15 trees," she says. "We could have put in 50." She adds that the trees planted at Azalea Park last year already are well on their way.

Check back in five years.

The city's Susan Pleiss, shown here at Riverview, rounded up volunteers to plant the plastic-sleeved green ash, silky dogwood, and black oak (among others).

PHOTO BY BILLY HUNT

#