COVER- Invasion: They live among us

They're beautiful– sometimes even a little seductive. But they replicate– quickly– and they're poised to choke the life out of some Central Virginia natives.

They're invasive plant species, and the threat is considered so serious that federal officials are studying the problem and the Virginia General Assembly has created an Invasive Species Council. Even Charlottesville is ready to launch a formal study of every park to formulate a plan to deal with weeds gone wild– although some people will quibble with the very idea of calling them "weeds."

Ruth Douglas, the local invasive alien plant project coordinator (really), strolls through Greenleaf Park, pointing out huge English ivy vines that were cut back this spring but are already sprouting again.

In Arlington, English ivy is so prolific, Douglas says, that some residents there requested that state legislators declare it a noxious weed. "The s**t hit the fan. There are English ivy societies," she says.

Apparently one woman's invasive species is is another's ornamental ground cover.

Douglas, a former botany professor at Piedmont Virginia Community College and a volunteer with the Virginia Native Plant Society, gives lots of talks about invasives. At one, she held up some Oriental bittersweet, which has beautiful orange flowers in the fall. Douglas thinks bittersweet is the worst invasive plant in the area.

"A woman came up afterward and said, 'I've been looking for that. Can I have it?'"she says.

It's the beauty of the invasives, combined with their rapid growth rate, that prompted people to import them in the first place.

"A lot of our invasives are from Asia or Europe," says Douglas, "where the climate is similar."

The notorious ailanthus, or Tree of Heaven– or, less charmingly, Stink Tree– came from China in the 1700s, and is now found– well, everywhere. Douglas notices some in Greenleaf Park.

"Very insidious," she murmurs. "You have to have the energy and time to keep after it. I feel like there's a place for herbicide– although a lot of people don't think so."

She sees another invasive– princess tree, the one with purple flowers that erupt in early May and that's common along Virginia byways. "It's sold as a fast-growing tree," Douglas says. And like so many invasives, it first got here as an exotic specimin sold in nurseries.

Another, wisteria, admired by many, climbs a park fence.

In spring, the multiflora rose is in beautiful bloom. "The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture promoted it in the '30s and '40s as a living fence," she notes. Now its thorns make it the scourge of anyone who wants a leisurely walk through the woods.

Douglas calls her invasive plant presentation "Good Intentions Gone Wild." Kudzu, the Japanese vine introduced in the 1930s to control erosion and provide fodder for cattle, is the poster child of invasive plants, but it doesn't creep onto local experts' top-five lists.

Douglas spies another invader so common that it barely registers as a non-native: Japanese honeysuckle. "This vine has probably destroyed more native habitat than any other three or four plants combined," she says.

At Washington Park, the invasives battle for supremacy. Douglas points to a mimosa– another fast-reproducing Asian import– that's being swallowed by Japanese honeysuckle and bittersweet. "You can see their weight is going to take that tree," she observes.

Over in the woods beside Dominion Power off Hydraulic Road there's been some clearing by the Rivanna Trails Foundation along Meadow Creek. Some cut-back ailanthus is already returning. Bittersweet and multiflora rose gleefully proliferate.

The one that dismays Douglas the most is garlic mustard. "It's just awful," she says. "It produces a poison that affects other plants. And to get rid of it, you can't just throw it away because it's already made seeds. You have to bag it."

One tree is so completely swaddled in Oriental bittersweet and grape vine, mummy style, that it's impossible to identify the species. But while strangled trees are certainly disheartening, what's so bad about plants joining our nation of immigrants? Can't they just assimilate?

"They disrupt natural areas," says Douglas. "They disrupt whole ecosystems. Everything is connected."

She mentions purple loosestrife,"the scourge of wetlands and moist meadows," which overpowers native plants, creating a monoculture. In Massachusetts, it's taken over a site that was home of numerous native orchids 100 years ago. Loosestrife has been declared a noxious weed in Virginia.

Autumn olive is another invasive that Douglas targets as disruptive to wildlife because predators can so easily get at birds nesting in its branches.

And yet, it grows fast, is attractive, smells good, and produces tasty berries that wildlife love. And the berries are high in lycopene for nutrition-loving humans. What's so wrong with that?

Nature writer Marlene Condon has an autumn olive in her yard. "It has a wonderful fragrance. I planted it when I first moved in and the soil was crappy. It's been here 20 years, and it has not taken over my yard," she says.

Condon says there's a place for such plants: areas where new construction has left subsoil in which native plants won't grow. And she believes plants running amok are the result of poor management.

"If you see a field full of autumn olive, it's because no one managed it," she says. "If it's not that, it would be Virginia cedar. People would still complain– and that's a native."

Condon objects to the term "invasive," because it sounds "as if these plants are evil," she says. "They're just doing what plants do."

What bothers Condon about the invasive plant movement is the use of pesticides. "It affects amphibians," she says, "because it's easily absorbed into their skin when they crawl over the plants."

People should either get rid of plants manually or just leave them alone, Condon says. "I think the cat's out of the bag. And they do support wildlife, contrary to what some people say."

"The cow's out of the barn," echoes bamboo aficionado Kevin Cox. "In the case of the most invasive species, containing them is a hopeless crusade. We'll never succeed with kudzu, ailanthus, lantana in the South, and water hyacinths."

Although he loathes ailanthus, Cox thinks it's crazy to spend thousands of dollars and man-hours trying to eradicate a tree that manages to plant itself in everything from open fields to the tiniest crack in urban asphalt. "You may as well accept that it's now a native species," he says, and that humans have had a role in the spread of it and other invasives.

"Eventually the natural order of predation and reproduction will triumph, and these so-called aliens will be put in their niche," Cox predicts.

Cox points to other species that are not very human friendly– but fully native– like poison ivy. "It has a very important place in the ecosystem," he says. "Deer eat it, and birds eat its berries."

As for his mature grove of fast-spreading bamboo, "There's no bamboo in my neighbors' yards," Cox notes.

What constitutes an invasive is debatable. Certainly, many plants identified in the National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife's booklet Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas– such as butterfly bush, Japanese spiraea, Bradford pear, and bamboo– are commonly found in local gardens.

Ruth Douglas had a butterfly bush in her yard before she realized it could escape and become naturalized. She dispatched it.

Yet Marlene Condon sees that as an overreaction to a plant favored by wildlife. She sadly recounts another case in which a mimosa owner was going to cut down her fast-replicating tree with the puffy pink flowers. "It's a beautiful tree, and hummingbirds love it," Condon says.

Brian Daly, assistant director of parks and recreation, is overseeing Charlottesville's study to find out just how over-run our area is.

"We're mapping into the city's GIS system to put together a plan," he says. The study, which should be completed in September, is a five-year plan that will include removal and containment of invasives and restoration of natives. Some will be removed manually, some with herbicides.

Daly says it's difficult to put a price on the cost of containing the spread. "A lot of the work is sweat equity, and it costs more to contract it out than to use staff or volunteers," he says.

In fact, volunteers took a chunk out of the English ivy and bamboo in Greenleaf Park earlier this spring. But it's an ongoing process, as Ruth Douglas' stroll through the park in May demonstrates.

Even Douglas, the invasives expert, is pragmatic about the realities of eradicating the new arrivals. "I'm not a nativist," she declares. "It's just not realistic."

Ruth Douglas is the invasive alien plant project coordinator for the Virginia Native Plant Society.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Arm-sized English ivy vines threatened to topple trees in Greenleaf Park until volunteers took a whack at them. Undeterred, new ivy is sprouting from the roots.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Ailanthus struggles to get over the fence into Greenleaf Park.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

SIDEBAR- Creepy critters: Invaders aren't all flora

Remember the gypsy moth, heralded as the doomsday insect that was going to defoliate the Shenandoah National Park on its way to decimating every tree on the Eastern seaboard?

"It didn't severely alter the landscape like people feared,"says horticulture extension agent Peter Warren.

Warren is on the look-out, however, for more invaders, both insect and aquatic, on the horizon– or already here. "You can never tell if it's going to be a big problem," he says.

Some non-natives have been around for so long that they can now call Central Virginia home: small-mouth and large-mouth bass, blue-gilled sunfish, and even channel catfish on the Eastern Shore. Those were introduced 200 years ago and are considered desirable additions, according to regional fisheries manager John Kauffman.

Less desirable: carp– introduced 100 years ago by the fish and wildlife department– and brown trout, released in Madison and Greene counties.

The worst source of new wildlife is– surprise– humans, especially people who dump exotic pets like snakes and other reptiles that outgrow their aquariums. The Everglades are now home to giant pythons battling alligators for supremacy as largest predator.

Will the most notorious recent foreign fish, the snakehead, soon be swimming the Rivanna? Kauffman thinks not. "We don't think it will go through the saltwater barrier," he says.

But if some yahoo decides to release one into the reservoir, all bets are off. And, Kauffman warns, the only legal snakehead is a dead snakehead.

Here are a few more aliens already here or headed this way:

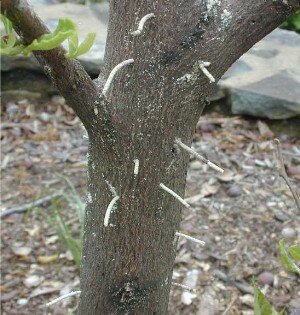

Asian ambrosia beetle: A relatively new pest, the Asian ambrosia beetle made its debut in Charlottesville in the past five years, Warren says. It bores very tiny holes into an ever-expanding variety of four or five-year-old trees, including dogwoods and maples, and pushes out toothpick shards from the tree. If left alone, it will kill the tree.

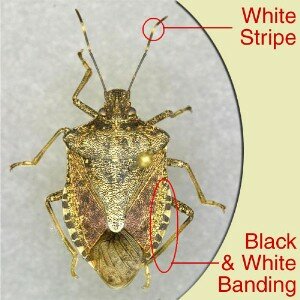

Brown marmorated stink bug: Not quite here, the nouveau stink bug has been sighted in Lynchburg. Like ladybugs, it invades houses. Worse for orchardists, "It's one of those insects whose mouth parts pierce and suck plants," says Warren, causing cosmetic damage to fruit trees like local favorites such as apples and peaches.

Emerald ash borer: This Asian export was discovered in Michigan in ash pallets. "We had a little bit of a scare when infected stock from there was sent down to Virginia," says Warren. While there are plenty of native boring beetles that usually infest dying or dead trees, this shiny, metallic-green menace attacks live ash trees. Warren suggests we stop planting ash trees when these are on the horizon.

Asian longhorned beetle: Another potential killer, the Asian longhorned beetle has been found in New York and Chicago and could head this way. MO: boring into and killing live trees. There's no effective treatment, and when they're found, it's necessary to cut down and chip the infested trees. "Devastating," says Warren.

Tiger mosquito: The black-and-white banded tiger mosquito has been around for about 10 years. Unlike native mosquitos that come out at dusk and lumber lazily on the breeze, the tiger seems to evade slapping, and it can suck blood all day long.

Asian clam: This tiny, half- to three-quarters inch clam is found in most local streams, says Streamwatch director John Murphy. It's been around for about 50 years and has built up large populations. "You can walk along the banks of the Rivanna and find shells," Murphy says. Its effect on local ecosystems? TBD. Often invasives become populous and take up niche space. "We don't know if that's the case with this clam, but it looks like it," Murphy says.

Giant crayfish: Two to three times larger than natives, this über crustacean has been spotted in the James. "We don't think it's gotten into the Rivanna," says Murphy. Crawdad lovers, take note.

Brown marmorated stink bug

PHOTO COURTESY VIRGINIA COOPERATIVE EXTENSION

The Asian ambrosia beetle leaves toothpick-like damage to trees.

PHOTO COURTESY VIRGINIA COOPERATIVE EXTENSION

Emerald ash borer

PHOTO COURTESY VIRGINIA COOPERATIVE EXTENSION

SIDEBAR- The invaders: Top 10 local threats

Which are the worst alien invaders ready to envelop Charlottesville in their lethal green embrace?

The Hook consulted botany prof Ruth Douglas and horticultural extension agent Peter Warren to come up with a list of the top 10 local invasive species. Such a list is necessarily subjective– another list might include porcelain berry, kudzu, and Japanese knotweed.

1. Oriental bittersweet: Ruth Douglas chooses this as the number-one invasive. The vine was introduced in the U.S. in the 1860s and is still used for landscaping. Bittersweet can survive in both open and shaded areas, where it wraps itself around trees and strangles the life out of them, preventing photosynthesis and breaking them with its excessive weight. Its beautiful fall berries are "the reason it's so popular," says Douglas.

2. Ailanthus (Tree of Heaven): When civil war left Beirut a bombed-out ruin, the only vegetation visible among the rubble was ailanthus. It's so impervious to urban conditions that it's found growing out of cracks in alleys in Charlottesville. Chances of it being the last tree standing are enhanced by a chemical it puts out that slows the growth of other plants. Stink tree looks like black walnut, and if you're not sure, just smell it.

3. Garlic mustard: Some call this herb– which came from Europe, probably for medicinal purposes– the worst of the plant intruders because it produces a poison that gets rid of surrounding plants and microbes. One plant produces hundreds of seeds, and once it's mature, experts recommend bagging the plant after pulling it up.

4. Japanese honeysuckle: The fragrant vine has been around so long that it seems to be part of the Southern landscape– and of New England, the midwest and California. A perennial, it twines over, under, around, and through native vegetation and trees until they're kaput.

5. English ivy: Its huge vines weigh down a tree and break off the limbs; its leaves can overshade a tree. Yet this killer is welcomed into many a yard. Check out the rehab at Greenleaf Park, where massive English ivy vines had to be sawed to prevent them from toppling trees. But even that didn't stop the determined vine, which is sprouting again from the roots. It also spreads by seed and from cuttings.

6. Paulownia (princess tree): Valued by the Japanese for its wood, and by gardeners for its purple clusters of flowers in the spring, a single princess tree can produce 20 million seeds. Anti-invasive forces recommend cutting the tree to the ground– but if you do so, you might want to sell the wood.

7. Japanese stilt grass: Found in every county in Virginia, stilt grass probably arrived as a packing material for porcelain around 1919. An opportunistic plant, it clumps in areas that are mowed, flooded or even on deer trails. Recent research found it produces a poison that can injure or kill near-by plants.

8. Akebia: Also known as chocolate vine, akebia follows the standard invasive pattern: ornamental, Asian, rapid growing– and it strangles native vegetation once it escapes from the garden.

9. Autumn olive: Tolerant of drought and poor soil, autumn olive has defenders who admire its silvery leaves and fragrant flowers. Its detractors decry its ability to take over fields and snuff native plants. Wildlife like its berries, and seeds are spread by animal and bird consumption. One autumn olive that was planted in a median on I-64 in the Tidewater area had to be removed because too many birds heading for it were being splatted by cars, according to Douglas.

10. Multiflora rose: The multiflora rose is in bloom now, and its beauty can almost make one forget what a prickly pest it is. The rapid climber was promoted as a "living fence" to confine livestock and as a crash barrier in highway medians. Its thorns add to its annoying habit, and may harm the nesting of native birds.

Oriental bittersweet

PHOTO COURTESY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Ailanthus

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Garlic mustard

PHOTO COURTESY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Japanese honeysuckle

PHOTO COURTESY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

English ivy

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Paulownia

PHOTO COURTESY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Japanese stilt grass

PHOTO COURTESY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Akebia

PHOTO COURTESY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Autumn olive

PHOTO COURTESY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Multiflora rose

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#

2 comments

I freaking hate these darn stinkbugs. They're here. In force.

They're terrible.