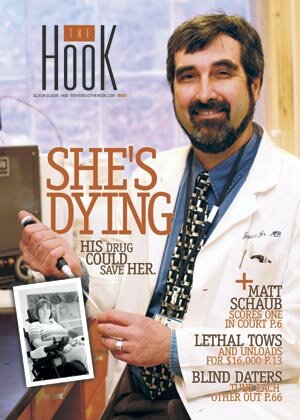

NEWS- Pharm-ed out: 'Gehrig' treatment gains support

Nearly 18 months after UVA pulled the plug on a drug study for the malady commonly known as Lou Gehrig's Disease, an experimental drug is now a step closer to reaching patients– thanks to a small Pittsburgh-based research firm that licensed the drug in March.

"This is a very, very positive development," says UVA neurologist James Bennett, who maintains his status as the drug's patent inventor while UVA holds the actual patent.

Pittsburgh-based Knopp Neurosciences wants to market pramipexole, the compound Bennett has been researching for nearly 10 years. According to Knopp CEO and president Michael Bozik, also a neurologist, the firm is currently applying for FDA approval to begin commercial testing of the compound, which has shown early promise in the treatment of the disease, formally known as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis or ALS.

As detailed in the Hook's February 24, 2005 cover story, "She's dying, his drug could save her," Bennett discovered pramipexole on the shelf of a German laboratory nearly 10 years ago. He believed the compound might be a key treatment for ALS, a fatal neurodegenerative disease that robs victims of the ability to walk, talk, swallow and, eventually, to breathe.

"We were fortunate to hear the story, listen to it, and respond to it," says Bozik of his company's decision. In fact, Bozik says, he left a high-level job with Bayer Healthcare to focus on pramipexole.

"I would not have left my position unless I was really convinced that the science of this is compelling," says Bozik, who hopes to begin meeting with the FDA within three months, though commencing studies may take much longer.

"The anxiety is that we have strong science and extremely high hopes, but we have to follow the code of regulations for drug development," says Bozic. "We want to make sure people don't think we're going to have the drug ready sooner than it will be."

Patience may be a necessity in the medical world, but many patients and families, understandably, are frustrated by more waiting.

Mary Jane Gentry, the subject of the Hook's cover story, was diagnosed in August 2003. But her case of ALS was particularly aggressive, and by January of 2004, she was already confined to a wheelchair. When Gentry heard about Bennett's Phase One study at UVA, she signed up, despite being told Bennett was testing the drug only for side effects.

But something unexpected happened. Nearly half of the 15 participants reported that the drug was having some positive effect. Gentry claimed she had regained movement in one of her hands, while other patients said they were swallowing more easily or finding it easier to stand unassisted.

Bennett says the anecdotes didn't prove anything scientifically, but he was intrigued. Though his study was slated to last just eight weeks, he asked the Human Investigations Committee at UVA, the ethical board that oversees all human research at the University, to extend the trial so that the subjects could continue to receive the drug.

The Committee refused, citing concerns including the fact that Bennett hadn't conducted enough animal testing to guarantee human safety and wondering if participants were merely buoyed by the "placebo effect."

Gentry, formerly a nurse with the UVA Health System, said she understood the need for solid science. But as her condition deteriorated, she questioned the committee's refusal.

"So what if the drug kills me?" she said. "The disease is going to anyway. If we can learn from the drug, then at least my life would have had some impact in its last few years."

Gentry died on May 26, 2005 of complications from pneumonia.

Three months later, after both the FDA and the UVA Committee approved several new protocols, Bennett was allowed to resume administering the drug to the 10 surviving participants.

Bev Nicola was one of them. Diagnosed with ALS in 2003 at age 63, Nicola first lost the ability to speak and to swallow, but while taking pramipexole, she regained some ability to articulate words. In the nine months between the end of Bennett's Phase One trial and resumption of the drug under a new status in September 2005, Nicola's condition deteriorated. She was hospitalized for several weeks in August 2005 with pneumonia, a common complication of ALS. But since that time, Nicola– now one of only five surviving members of the original group– reports that she has regained some strength.

"I'm feeling good and find my breathing is good, and I seem to swallow better," she writes in an email. Typing is now her sole form of communication. But she adds, "I have lost some hand and arm movement."

Bennett says that between 35 and 40 patients like Nicola are taking the drug under the FDA's "Phase One Open Label" protocol, which allows terminally ill patients access to experimental drugs on a compassionate basis. In addition, Bennett says, a new bill is being considered by the U.S. Senate that would allow terminally ill patients faster access to experimental treatments.

In addition to those 35 to 40 patients who are taking 60mg per day of the drug, Bennett says there are three other research studies under way around the country– one at UVA, one at University of Pittsburgh, and one at the University of Nebraska. Those three "futility" studies– involving a total of no more than 40 people taking 30mg per day– are "looking at whether there's any early evidence that taking the drug at a low dose appears to alter the course of the disease."

In another UVA study testing patients' tolerance of much higher doses, four participants have been escalated to a daily dose of 300mg, 10 times the dose given to the original study group.

Bennett has hypothesized that the loss of motor neuron function is a result of damage to nerve cells from free radicals. Pramipexole, the chemical mirror image of a Parkinson's drug called Mirapex, is a free radical scavenger, and Bennett hopes it might slow– or even reverse– that damage. (Unlike Mirapex, however, pramipexole does not mimic the neurotransmitter dopamine and so does not have the same serious side effects.)

But getting a drug from hypothesis to drugstore shelf is a long and arduous road, Bennett learned. And it's a particularly painful trip when the patients he hopes to help are dying around him.

For now, Bennett remains cautiously optimistic that pramipexole will play a healing role for at least some of the 30,000 Americans living with ALS.

"It depends on how you spin the data," he says of the results he's seeing in the studies. "I'm encouraged by the fact that people seem to tolerate the drug very well."

And giving the higher dose is a critical step.

"We'll be able to give a high enough dose so that if the drug doesn't work," he says, "we'll be able to say we've given it a real test."

Dr. James Bennett celebrates the news: "In order for any potential therapeutic drug to move out into the world, it has to be commercialized."

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#