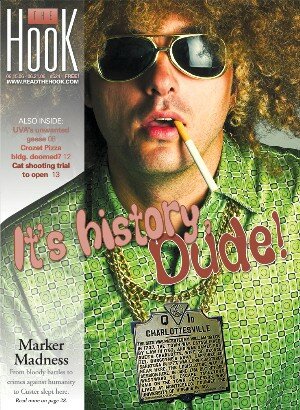

COVER- Drive-by history: GPS marks the spot

In a town with colonial origins like Charlottesville, you can barely spit without hitting a historical marker. And driving through Albemarle County and the Old Dominion, it's obvious lots of important things happened here, even if you can't actually read the markers when you're zooming by at 55 miles per hour.

Local history has just entered the 21st century. Up until recently, the only resource for tracking down and touring Virginia's more than 2,000 markers was A Guidebook to Virginia's Historical Markers, published in 1994 and available for $18.95.

Things have gotten easier for history buffs. Jason Watson has photographed and taken the GPS coordinates of 1,453 historical markers in 12 states, and 1,209 of those are in Virginia. He's put photos of text and interactive maps on his website, www.historical-markers.org, which is getting about 5,000 hits a month.

Watson was inspired to take on this project when he was working on his MBA and driving up to George Mason University from Charlottesville several times a week. "I do a lot of traveling and have always been interested in the thousands of gray markers that dot the highways, but, like most, was unable to read while whizzing by on the highway."

He had another motive: "There are several research ideas I wanted to work on related to mapping and searching," he says.

The historical marker program was ripe for mapping. A new guide is coming out from the University of Virginia Press, but the state has no online listing of its more than 2,000 markers on its website– although that is in the plan.

Virginia's historical marker program started in 1927, one of the first in the country. It's administered by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, which considers new candidates quarterly.

Anyone can sponsor a marker, as long as the person, place, or event has regional, state or national significance. And as long as the sponsor can come up with $1,350, the current cost of casting the aluminum alloy markers. Installation and maintenance are handled by the Virginia Department of Transportation.

Much like haiku, markers must distill down to 100 words the significance of, say, Monticello or the University of Virginia. Marker texts are rigorously scrutinized for historical accuracy. And occasionally, they're controversial [see sidebar].

Historian/radio host Coy Barefoot was founding chairman of Charlottesville's historic resources task force in the late 1990s. "We decided we needed more markers in the city, where people walk around," says Barefoot.

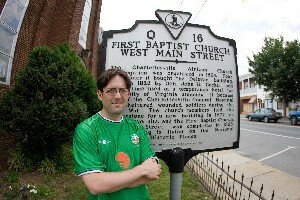

That impetus led to a marker for Woolen Mills, the Old Stone Tavern marker on Market between 4th and 5th streets, the First Baptist Church marker on West Main near the train station, Jack Jouett's Ride on High Street at Courthouse Square, and Charlottesville General Hospital on the corner of JPA and West Main.

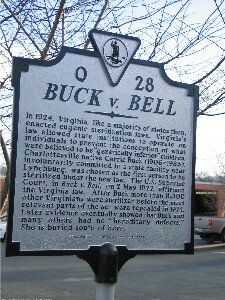

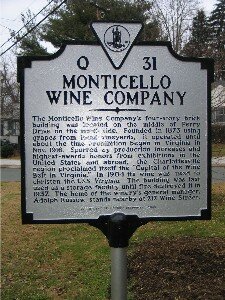

Recent additions are the Monticello Wine Company marker on McIntire and Perry, the Georgia O'Keefe-stayed-here marker on Wertland, and the Buck v. Bell marker at Region Ten. That last one commemorates Charlottesville's dubious role in the state's early 20th century effort that made resident Carrie Buck the first of more than 8,000 people believed "genetically inferior" to be sterilized.

Over the years, the markers have moved from Revolutionary and Civil War commemoration to topics of social justice, such as Buck v. Bell, or the Jefferson School marker that remembers the city's segregationist past. The Monacan Indian Village marker on U.S. 29 notes the area's Native America presence.

Rule of thumb for an event to get a marker– 50 years or older, although exceptions may be made, such as for the Civil Rights movement.

Why dot byways with hard-to-read snatches of history, anyway?

"It reminds you history is not just written as words in books," says Barefoot. "It's written on the landscape, it's written on brick and on stone, in the built environment and in the natural landscape. These markers remind us of that, and they make the past really speak to us as we move through the city." And the county. And the state, and the country.

PHOTO BY BILL EMORY

Jason Watson has avoided getting hit in the course of photographing almost 1,500 highway markers and putting their global position coordinates on a historical marker website.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

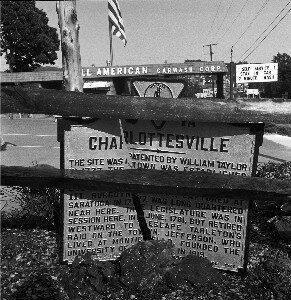

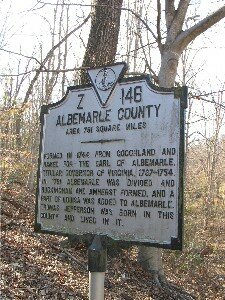

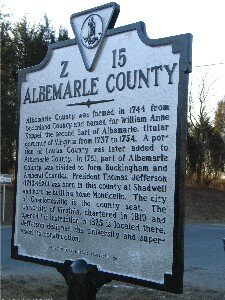

An Albemarle County marker from 1946 focuses on the importance of Goochland in the county's history, and oh by the way, a guy named Thomas Jefferson lived here.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

In the new-and-improved 2003 Albemarle marker, we learn that Jefferson was President, his home is called Monticello and he had something to do with the design of the University of Virginia.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes' 1927 opinion that "three generations of imbeciles is enough" made Carrie Bell the first woman sterilized in Virginia.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

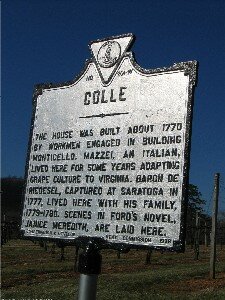

If only we knew who Baron de Riedesel was– or who the author Ford was who wrote Janice Meredith.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

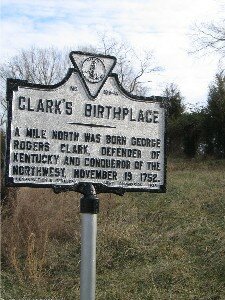

Albemarle's shortest highway marker...

PHOTO JASON WATSON

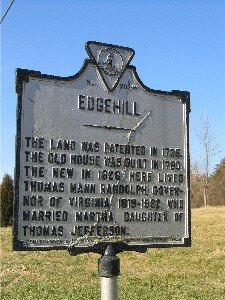

The Edgehill marker on Route 250 near Shadwell has seen better days.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

General George Custer sneaks onto his third historical marker in the area (the other two being the controversial "surrender" marker and the Rio Hill skirmish marker).

PHOTO JASON WATSON

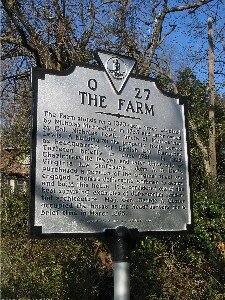

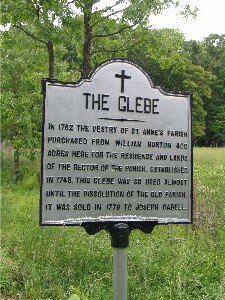

This is not an official historical marker– you can tell by the absence of a letter and number at the top. But someone felt it important to remember that the now-defunct St. Anne's Parish rector lived here, and the land was sold in 1779 to Joseph Cabell.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

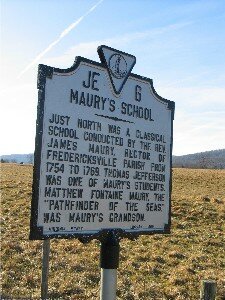

Jefferson studied here. And leisurely travelers on Route 231 know that Matthew Fontaine Maury was the "Pathfinder of the Seas."

PHOTO JASON WATSON

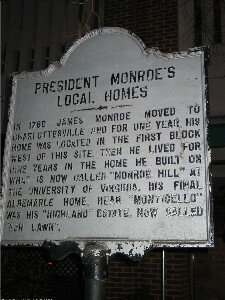

Lesser, fifth President James Monroe has almost as many markers around town as Jefferson– although this one on Market Street is not an official state historical marker and could use a makeover.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

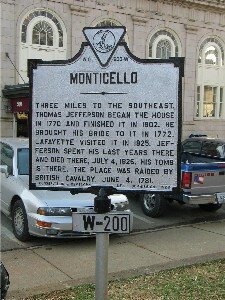

One of the oldest area markers, this one isn't anywhere close to Jefferson's home. Strollers around Court Square can imagine what they'd say if they were writing the text for Charlottesville's most famous landmark.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

The city's newest marker notes Charlottesville had a wine industry way before Patricia Kluge came to town.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

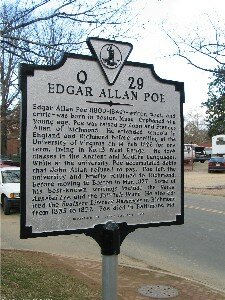

Note of Edgar Allan Poe's brief tenure at the University of Virginia is a relatively new addition to McCormick Road.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

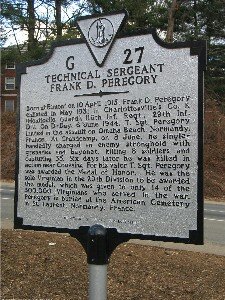

The heroics of Technical Sergeant Frank D. Peregory likely would be forgotten were it not for this reminder at U.S. 29 and University Drive.

PHOTO JASON WATSON

SIDEBAR- Historical rewrite: It's all who you know

He was born here in blah-blah-blah. He was a key figure in the great blah-blah-blah. He died uttering his trademark slogan....

Documenting the facts on somber historical markers sounds simple enough, right? And yet, dry footnotes to history can occasionally ignite controversy. In Charlottesville, it's happened twice.

First was the bogus Tarleton's Oak story. For much of the 20th century, a state historical marker proclaimed that the British colonel spent the night under a giant tree that used to shade Tarleton's Oak Service Station on High Street.

In 1997, however, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources yanked up the marker when it discovered that Tarleton did not camp there. It seems the myth began after Edison Moving Pictures came to town in 1912 to film Colonel Banastre Tarleton's raid and the failed capture of Jefferson, and made the oak a way station for the British troops. The movie set made its way into local lore.

A new and improved marker, "The Farm," was erected on Jefferson Street where Tarleton actually stayed to clear up the legend. And the ancient, diseased oak became mulch.

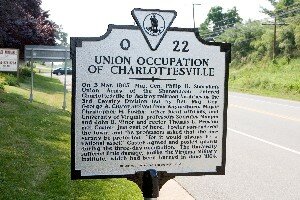

Another controversial sign pitted UVA heavyweights against General George Custer's fan club in a semantic battle. Did Charlottesville surrender to Union troops, or was it merely occupied?

In 2000, the Little Big Horn Associates got approval from the Department of Historic Resources for a marker near UVA Chapel titled: "Charlottesville Surrendered." It detailed how on March 3, 1865, a white-handkerchief-waving delegation led by the town's mayor, Christopher Fowler, and three university representatives met the victorious Major General Custer arriving from the west, and asked for protection so the university wouldn't be torched as Virginia Military Institute had been earlier. Custer agreed, and the university was spared during the federal troops' three-day occupation.

The marker went up in summer 2000. A few months later, then-UVA Rector Jack Ackerly complained.

"I didn't think the marker belonged there," he told Coy Barefoot, who reported on the incident in C-ville Weekly in June 2001. "We had already told the [Little Big Horn Associates] that we didn't want their marker. We didn't think it belonged on university grounds. In addition, there was an inaccuracy in the language of the marker. It said that the university surrendered when in fact it did not."

Another complaint: the zealousness of the Custer contingent in documenting every move the doomed general made, when local notables Thomas Jefferson and Edgar Allan Poe still didn't have their own markers at the university. (The latter become marker-worthy in 2003 with a notice of one term at the university near his room Number 13 on the West Range.) Custer is mentioned on the "Skirmish at Rio Hill" marker, and he managed to worm his way onto the revised Tarleton marker on Jefferson Street, which notes that Custer stayed at the same residence there that Tarleton earlier occupied.

The surrender sign was removed, and a new marker went up on Route 250 near Zazus restaurant, well west of the Chapel, where the event took place. The new marker, "Union Occupation of Charlottesville," made no mention of surrender or white handkerchiefs.

"The history that gets told depends on who's telling the story, under what circumstances, and why," Barefoot wrote. "The past stays the same. It's history that changes."

The process of marker text approval is very exacting, and some historians agree that, in fact, the university did surrender. Others argued, how can a university surrender?

Says Barefoot in a recent interview with the Hook, "We learn more about the power of telling a story because someone at UVA had the power to change the telling of the story."

That's a history lesson that won't appear on a historical marker.

The revised history of George Custer's stay is now safely away from where those events took place.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

SIDEBAR- Historical markers we'd like to see

The Virginia Department of Historic Resources likes a good 50 years before commemorating a person, place or event as historic. Will these local sites one day bear the silver seal of history?

George Allen's office: The U.S. Senator, who lived on Montalto during his law school years, bought this historic building in 1978 as he started his law practice and his first runs for elected office. Although he hasn't lived in Charlottesville since elected Governor in 1994, he continued to own the East Jefferson Street building after starting his career in Washington.

Lane High School: A symbol of Charlottesville's segregated past, Lane was integrated in 1959, following a year of massive resistance in which the city shut down Lane and Venable Elementary rather than allow black students to attend. The building now houses Albemarle County's offices.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Trax: Dave Matthews, founder of the popular rock-jam group bearing his name, played Tuesdays at the nightclub here in the early 1990s before the band became world famous. The University of Virginia demolished the building in January 2003 to make room for its expanding medical complex. Alternate marker: Miller's restaurant.

Satyendra Huja's house: The visionary city planner urged Charlottesville to brick over its famous Downtown Mall in the mid-1970s, saving it from the dying-downtown syndrome so prevalent at the end of the 20th century. In the course of his 30 years with the city, the now-retired Huja also jump-started Charlottesville's landscaping and flowers, and its Percent for Art program that funds the city's famous Art in Place sculptures.

FILE PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

Charlottesville Pavilion: Coran Capshaw, the manager of the Dave Matthews Band who went on to own many commercial properties in Charlottesville, constructed the pavilion in 2005 after obtaining a long-term lease from the city. While the soaring canopy was derided as the "lobster trap," it may become the iconic landmark for the city, sorta like the Eiffel Tower for Paris– but with Lyle Lovett, James Brown, and Willie Nelson playing underneath.

C&O: Before Charlottesville became a gourmet mecca, the town was a dining backwater until 1976, when Sandy McAdams and Phillip Stafford took a former dive diner across the street from the Chesapeake and Ohio train station and made it a premier eatery. The restaurant received a rave review in the New York Times, putting Charlottesville on the culinary map.

The Ark: Crozet was just a sleepy village when a movie called Evan Almighty was filmed here in 2006 and the ark was constructed as part of its set. After Evan, could Crozet became a popular location for movies, leading to the moniker of "Hollywood East"?

Vinegar Hill: The Omni Hotel stands on what was once part of Main Street, where many African-American businesses stood, until city fathers razed them and the rest of the neighborhood in the mid-1960s, as part of a popular concept at that time called "urban renewal."

The Hampton Inn: Thanks to the sleuthing of a USA Today reporter, historians at Monticello now believe that Sally Hemings, the slave/mistress of Thomas Jefferson, lived and is probably also buried at the corner of West Main and 10th streets, today the site of the Hampton Inn. However, the wording for this historic marker could turn into a multi-year controversy!

#

1 comment

The City did not shut down Lane and Venable. The State of Virginia closed them.