NEWS- Crash pilot: 'I'm not going to give up yet'

The final radio transmission from the pilot of the ill-fated flight that crashed June 14 near North Garden was, "I'm not going to give up yet."

The chilling excerpt, released as part of a preliminary report on the crash by the National Transportation Safety Board, indicates that pilot David I. Brown was trying to find a tiny grass airstrip in the fog and rain. Brown, an instrument-rated pilot attempting to land at an airport with no support for instrument approaches, was apparently searching for a break in the clouds to enable a visual approach.

Brown, 55, and his passenger, friend, and business colleague Robert H. Baldwin, 75, died when Brown's single-engine Beechcraft Bonanza crashed and burned in a pasture along Plank Road, about half a mile southeast of the tiny runway.

"It's a little too cloudy at the moment," Brown reported to a Northern Virginia air traffic controller when the plane was at 4,000 feet. "Can you get me any lower?"

"That's as low as I can give," the controller responded.

A moment later, Brown seems to indicate that he's visually located the Bundoran air strip as he declines the controller's offer of a northwest approach. "Actually," Brown said, "the field is directly under me if I could, ah, spiral down."

The report indicates that Brown had landed at the mountain-surrounded airstrip 25 to 30 times in the past– but never during rain, which was falling at the time of the accident. In bad weather, according to the report, Brown would land at the Charlottesville-Albemarle Airport, which offers runway lights, a control tower, and electronic assistance for instrument approaches.

The report indicates that the local Bundoran manager left Brown a phone message that morning offering to pick the men up at the airport, but was not sure if the message was received. Although the manager, David Hamilton, reports that he had heard the plane overhead, he assumed that Brown would land at the larger airport. However, as previously reported, the better-equipped facility received no request for a landing from Brown on the day of the fiery crash.

The NTSB sets the crash time as 11:14am, 13 minutes earlier than previously reported, and says the purpose of the trip was for the men to work on conservation easements. Baldwin was the founder and Brown the regional director of New Hampshire-based Qroe Farm Preservation Development, and the two were considered pioneers in creative development of farmland. Qroe purchased Bundoran Farm in January and had announced plans to build 88 homesites on its 2,300 acres.

Among the features of Bundoran is the grass airstrip that former owner and avid pilot Fred Scott Jr. says he commissioned to be built by Faulconer Construction in the 1970s. According to Scott's website, the 3,000-foot-long, 100-foot-wide airstrip has an incline as well as a bend "in excess of 15 degrees." Further complicating any landing, Scott's site warns that animals may have burrowed holes in the runway, and an aerial photo shows trees and hills almost at its edge.

The NTSB report notes that Brown had 3,650 hours of flight time, was FAA-rated for instrument flying, and held a commercial pilot's license, among the higher rankings in general aviation or among private pilots.

Ironically, however, a report from the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association's Air Safety Foundation found that commercially rated pilots actually account for the largest proportion of "stall/spin" accidents. The Foundation conjectures that such pilots "may have grown complacent in their skills, or lack proficiency or understanding in aircraft operations at the corner of the flight envelope."

AOPA indicates that stalls and spins can be relatively harmless at high altitudes because despite losing at least 1,000 feet of altitude per spin, pilots have room to maneuver back to steady flight. However, low-level maneuvering presents two potentially fatal phenomena for a pilot: slower speeds and limited altitude for recovery.

Beechcraft Bonanza pilots typically land at around 70 knots, less than half their cruising speed and perilously close to stall speed. Any abrupt maneuver, AOPA warns– particularly any lift of the nose– can put a plane into an immediate stall and spin. AOPA's safety report is entitled, "Stall/spin: Entry point for crash and burn?"

The NTSB accident report says that Bundoran manager Hamilton, who had flown with Brown twice, reported that "the pilot had to make (what the manager felt) was a sharp left turn to avoid terrain before landing on the runway."

Contrary to one initial report from the FAA, the NTSB found no evidence that the plane had struck overhead wires or any other obstacle. And a check by the Hook of the two electrical utilities that serve that part of Albemarle County found no reports of outages the day of the crash.

The NTSB report found that the landing gear appeared to have been lowered. Moreover, the inspector found a hole in the ground containing the plane's three propeller blades and part of its propeller hub– an indication that the impact occurred nose down, suggesting a high rate of descent, which the Air Safety Foundation says is "typical of stall/spin scenarios."

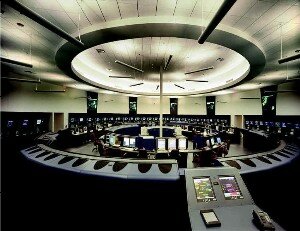

FAA spokespersons have indicated that the controller with whom the plane was communicating was located at the FAA's Potomac Terminal Radar Approach Control, or TRACON, in Flint Hill, a military installation near Warrenton. The TRACON keeps air traffic separate at airports without a tower of their own.

As plane number N202EN made its final approach in the fog and rain, Brown thanked the TRACON for approval for a visual approach, signalled his switch from an instrument to a visual radio frequency, and sent his final recorded radio transmission: "Ah, roger two echo november, I'm not going to give up yet."

Brown was talking to this TRACON near Warrenton

GOVERNMENT PHOTO

[Note: production gaffes caused multiple mistakes in the caption and credit of this photo. Such mistakes have been corrected in this online edition.]

#