ON ARCHITECTURE- You façadist! Views collide over First & Main

As the Downtown Mall celebrates its 30th birthday, a fierce debate is brewing over the direction it will take in the next 30. On one side are preservationists who want to retain the Mall's historic character. On the other: developers and growth advocates who want to realize the urban vision the City laid out nearly three years ago when it changed its zoning laws to encourage denser development.

At a June 19 City Council meeting, the two sides collided as developer Keith Woodard asked Council to overturn a Charlottesville Board of Architectual Review recommendation regarding a demolition request. Woodard had asked to level everything but the facades of buildings he owns between 101 and 111 East Market Street to make room for his First & Main project.

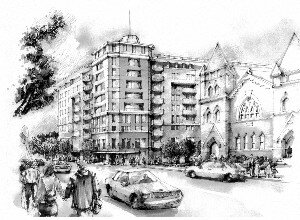

Located at the very heart of the Mall across from the Jefferson Theater, it might become a massive nine-story, mixed-use building with an automated underground parking facility.

The BAR, trying to appease both sides, denied the façade-saving demolition request, allowing instead the leveling of one building, the partial demolition of another, and the complete preservation of 101 East Market, currently the home of the Charlottesville Community Design Center. Woodard appealed the BAR decision, according to Mayor David Brown, because it would botch the installation of his planned automated underground parking garage, a Jetsons-sounding idea which might become more costly and problematic if he were required to preserve the building interiors.

"I consider it a big deal to overturn the BAR," says Brown, who– along with vice mayor Kevin Lynch– were almost ready to vote no on Woodard's request. "I'm very reluctant to embrace this kind of demolition," Brown said, referring to saving only the facades.

Nevertheless, after outgoing Councilor Blake Caravati (this was his final meeting) made an appeal on Woodard's behalf, Brown and the other councilors voted to defer their decision and convene a BAR work group to study the project.

"I'm really excited by the First & Main project," says Caravati. "This is going to set the trend for what is going to be built on the Mall. Keith Woodard is a very straight-forward guy, and he's very interested in doing what's right for Charlottesville... and for himself too, of course."

Apparently, Caravati's enthusiam for the project was enough to convince the rest of Council to second-guess the BAR.

"There's an incentive for us to be realistic about this," says Brown, trying to explain Council's observations by referring to the economic and social benefits of such a development, "but we want to make sure we're not headed in the wrong direction."

As Brown points out, even if Council had denied Woodard's demolition request, the building could still be demolished. "If the developer puts the property up for sale for a year without finding a buyer, then he can go ahead and demolish the buildings," says Brown. "In part, we deferred it because this is going to be an issue for the next Council."

The decision came as a bit of a shock to some BAR members and preservationists, who believe the city's existing guidelines are sufficient and who considered their recommendation a compromise to begin with.

"Remember, it's half a block of the Downtown Mall we're talking about," says BAR chair Fred Wolf. "This project would have a huge impact, right at the most identifiable space in the city besides the Lawn. It seems to me it's a small concession to work with our recommendations."

Indeed, the BAR hardly seems out to quash tall projects. Just recently, the BAR approved Bill Atwood's Waterhouse project, a nine-story mixed-use complex slated to rise over the Downtown Tire building on Water Street and extend back to South Street.

Like First & Main, Waterhouse will dramatically change the street-scape and will feature an underground parking facility, but there were some key differences: variety of buildings dates on the site, there's a large open parking lot space there, and the fact that it's not on the Mall. As Wolf points out, "There was a little more flexibility on that site" than the First & Main site, which, as Wolf reminds us, is in the center of a historic district.

Not to mention that Waterhouse already has a nine-story neighbor, the lonely and sometimes polarizing Lewis & Clark Square, a structure designed by VMDO Architects and built in the late '80s, in a City Council-approved slap at the BAR, according to former BAR member Jack Rinehart.

"We fought it the best we could," says Rinehart, who would rather see these tall buildings go up on the outskirts of the Mall, "but City council overruled us. It was kind of a fait d'compli from the start."

While the new zoning has certainly influenced projects like First & Main and Waterhouse, it's worth noting that the 9-story height regulation is nothing new. As Lewis & Clark makes clear, developers were already allowed to build 9-story buildings (101 feet) under the old zoning regulations. Of course, another factor needs to be considered as well, one less idealistic than the new zoning laws, and that's the price of land around the Mall. Taller buildings give developers more of a financial incentive because they can sell more units.

"It's a little bit scary that the BAR decisions aren't being respected," says Gina Haney, president of Piedmont Preservation, who had originally advocated saving all the buildings. "We don't support this kind of façadism... it's such a dangerous precedent for the Mall. We should really be retaining the buildings."

In a letter sent to councilors before the June 19 meeting, Piedmont Preservation pointed out that Woodard "already knew what he was getting into" when he bought the properties, at least three of which have been recognized since the early '80s by local, state, and federal authorities as contributing properties to the historic district.

In addition, Preservation members reminded Council that the whole situation reeks of deja vu. In 2000, the BAR twice denied developer Lee Danielson permission to demolish the buildings, but was later overruled by Council's vote to allow partial demolition. Since then, the letter states, the BAR has supported that "generous" ruling when presented with demolition requests for the buildings.

Piedmont Preservation's letter describes Woodard's facade-only scheme as "tokenism" that "lacks both the authenticity of an old building and the potential originality of a new one." It also points out the structural risks of facadism, using the recent collapse of the Albemarle County Juvenile Court House as an example. As the letter states, "A new building fashioned out of scavenged rubble is not a historic structure. It is a loss against which no insurance policy can protect."

Finally, the letter calls the First & Main project "a direct challenge" to the City's preservation law that will "eviscerate" two centrally located historic buildings. The project would, the letter states, "overwhelm its neighbors, tower over Lee Park, and open the door to similar schemes."

Still, neither side seems willing to spoil the process. As Wolf points out, "When it comes to preservation versus growth, as long as it's described as 'either/or,' you're going to have problems."

Indeed, even Caravati seems to recognize the need to be careful.

"What we do now is really important," he says. "I think it's important to get the design right, to think in the long-term what's best for Charlottesville, so we won't regret it when we're in our graves."

Likewise, preservationists don't want to be seen as anti-growth.

"We aren't against dense development," says Haney. "Preservation shouldn't be about boarding up buildings. Density is good if it's sensitively built. But you also need to respect the city preservation ordinance."

Still, the First & Main project presents the city with a difficult dilemma. On the one hand, the project is precisely what the city asked for when it changed its zoning laws to encourage denser development. On the other hand, it's in the center of a prized historic district. Should the city enforce the BAR recommendations, which might fatally stall projects like First & Main? Or does the desire to urbanize Charlottesville require it to cast a colder eye on the past?

"I think we're expiencing some growing pains," admits Brown, "as we deal with the realization of Charlottesville becoming urban."

"Remember what happened to Paris in the 1860s?" Caravati asks, trying to illustrate his thoughts about the First & Main project by alluding to the work of Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the famous urban planner commissioned by Napoleon III to "modernize" the city. Haussmann proceeded to demolish much of the old medieval city to make way for the expansive boulevards and gardens the city has since become famous for. It's estimated that more than half the buildings in Paris were razed under Haussmann's modernizing effort.

It's Caravati's offhanded way of saying that demolition isn't always a bad thing, especially if a city wants to pursue a new vision of itself. Paris, as it turned out, didn't become the "city of light" until after Hausmann demolished half of it.

Of course, Caravati doesn't mention the fact that not everybody at the time was happy about the "destruction" of Paris. Or that once something is demolished, there's nothing left to remember or appreciate anyway.

As the historian Robert Herbert tells it, the demolition of historic Paris in the 1860s greatly troubled and disoriented the citizenry. "The continuous destruction of physical Paris led to a destruction of social Paris as well," he wrote. Likewise, some would argue that the Downtown Mall's social fabric is already a buzz and worth preserving as it is. Why risk ruining it with massive new building projects?

Still, destruction has its rewards. As Herbert also mentions, the architectural upheaval in Paris inspired the Impressionists, who– by attempting to depict this disjointed new world– gave birth to a whole new way of seeing things.

Piedmont Preservation has called First & Main's facade-only demolition scheme "tokenism" that will "eviscerate" two centrally located historic buildings.

A2RCI Architect Greg Brezinski

#