COVER- On the download: Can our indie stores survive?

After 20 years as a commercial pilot, Cal Glattfelder chose to brave a new kind of turbulence when he entered a music industry buffeted by illegal downloads. Glattfelder purchased a music store that he named Sidetracks from Spencer Lathrop, who had founded the place as "Spencer's 206" 10 years earlier.

"I was tired of the corporate world," Glattfelder explains. "I love music and wanted to be my own boss. I initially looked at the place back in 2001 and decided not to do it for a while. But two years later, I decided to make the jump."

During that time, Glattfelder determined that even the dire predictions of the imminent demise of music retail couldn't derail the John-Cusack-in-High Fidelity coolness of owning a record shop in a happening little arts haven.

"It was before the iPod," he sighs.

That adorable little white gadget was actually released in 2001, but it didn't start having an impact on traditional music sellers until a 2003 revision lowered the price and brought its iTunes software to the dominant Windows computing platform. All of a sudden, the iPod was within reach of most music lovers.

And with the iPod came a surge in illegal downloads. Although destined to be played on perfectly legal devices, those downloads created panic in some corners of the music industry. The Recording Industry Association of America, RIAA, began issuing ominous predictions about the future– and suing teenagers, even pre-teenagers.

A university pastime

Approximately a mile west of Sidetracks, in the heart of the UVA Corner district stands Plan 9, Charlottesville's biggest indie music store. When recent commerce school graduate Julia Thies was in school, she was a Plan 9 regular.

"They have the listening stations," says Thies. "One time I went in and spotted the new Ziggy Marley album after I'd heard him perform on Conan. I listened to the CD, got hooked, and bought it."

More frugal music fans, however, do not shell out $18 for an album. Instead, they spring for a few nickels for a blank CD and either pay about $10 to download the album legally or snag it free from an illegal site.

Despite the controversies and lawsuits, downloading and CD-burning continue as University pasttimes, and Kelly Wilkes, manager of Plan 9, believes that all retailers have felt the hit.

"Free" Wilkes says, "is just not going to be legal." To be sure it stays that way, in 2003 the RIAA unleashed a barrage of lawsuits– including one against a Princeton University student and one targeting a 12-year-old in New York. "The way the RIAA went about it," says Wilkes, "was short-term and vigilante."

In the latest round of lawsuits, Texas teenager David Gruebel finds himself a target. Fortunately for Gruebel, the Nettwerk Music Group (the same small conglomerate that signed Charlottesville's own Hackensaw Boys last year) is funding his defense through their Save The Music Fan foundation, a non-profit group based in Canada.

"Music is ubiquitous; it's a utility like water. It's not a pair of pants," says Nettwerk president Terry McBride on the organization's website. "Litigation is destructive. We're a creative community, so this approach makes no sense at all."

It's a bold step. Countless outspoken artists have stepped up on both the pro- and anti-peer-to-peer camps over the years, but this is the most dramatic example yet of a music industry figure fighting the trade group that was created to represent him.

Hackensaw accordion/harmonica player Jesse Fiske is happy with his label's stance. "I think this is a very noble thing," he says. "I'm glad to be affiliated with someone who's looking out for people."

Dr. Moreno goes to Washington

One powerful person concerned about the music industry's tactics is Senator Norm Coleman (R-MN), chair of the Senate's permanent subcommittee of investigations. Back in 1970, a longhaired Coleman was a Hofstra University activist whose protests led to a campus shutdown in response to the Kent State shootings. Perhaps memories of his carefree days as a roadie for Ten Years After (the band best known for their performance at Woodstock and the hippie anthem "I'd Love To Change The World") provoked Coleman's sympathetic feelings for music fans threatened with fines of as much as $150,000 per downloaded song.

When Coleman took the issue to his subcommittee's hearings on Capitol Hill two years ago– with rapper Chuck D by his side– he questioned the industry's alleged privacy invasions and subpoena authority. He also called in an old Hofstra buddy, Dr. Jonathan Moreno, director of UVA's center for bioethics.

"These file sharers are people who wouldn't think of stealing from a mom and pop music store," Moreno says. "The industry needs to put a face on itself– the people behind the scenes."

Could Glattfelder be that face?

"Indie" store strategies

Glattfelder's passion for music goes back to his years as a DJ on WUVT in Blacksburg. Hand-painted shelves featuring Glattfelder's favorites– the Allman Brothers Band, Jimi Hendrix, the Who– soar toward exposed ceiling ducts in this former auto repair bay. Signs highlight emerging local artists, and toward the back stands an assortment of used CDs, cassette tapes, and vinyl records.

"Business has been hard," he says, turning serious, "especially since CD prices are high."

Sidetracks, though, does offer a used CD selection that Glattfelder says draws university students and money-challenged downtowners. For around $6, Glattfelder will ring up classics such as Simon and Garfunkel's Greatest Hits.

"They have a great selection of used CDs– not rejects, but actually good CDs," says record patron Thies.

Over at Plan 9, the albums might run slightly more than at Sidetracks, but Plan 9 has a larger stash of used CDs.

"We hire people who truly love music, want to dialogue with the customer, and can turn people onto music," says Wilkes. "If a customer can't find an obscure title, Plan 9 and Sidetracks will seek out and special order the album."

"Plan 9 has the stuff that Best Buy, Sam Goody, etc. don't have," says music patron Thies. "They have all the random stuff I'm into: Bela Fleck, Ziggy, old, obscure Rolling Stones albums, live Widespread albums, lots of folk rock and unheard-of artists." She adds, "But they still have the mainstream stuff if you just need a little Britney."

Wilkes sees diversity as the key to Plan 9's survival and success. The regional chain headquartered in Richmond has recreated itself at least once already. From a scruffy storefront across from the Byrd Theater in the Carydown district, Plan 9 introduced many Virginians to the ideas of a used album store in 1981. Now operating five stores across the state, including the two in Charlottesville, Plan 9 management believes it's fighting just as noble a battle as Sidetracks.

"I think the CD prices that have been mandated through distributors have undercut our ability to be successful," says Plan 9 manager and current Satellite Ballroom booking agent Danny Shea. "When you see an $18.99 CD, it's overpriced. It's not worth that much. Plan 9 has done a lot to aggressively try to keep CD prices down over the years."

Plan 9's solution appears to be cutting its margins and the cultivation of a certain cultural atmosphere, one defined as much by goofy trinkets and smart-aleck refrigerator magnets as by CDs, t-shirts, and posters.

"Now we have a coffee shop and a lounge type area, and the Ballroom ties into this too," adds Shea. "We're moving into a scenario where we have kinetic things that are tied in together.

"The big issue with me is seeing the death of the hangout," he continues. "If people are migrating toward doing it on a computer, they're not interacting with a human being."

Ironically enough, guess what Plan 9's planning for the next big reincarnation?

"Clearly digital downloads and sales are here to stay, and we know that," says Wilkes. "We're working on our own download store."

As Wilkes explains the system they'll use, it becomes clear that it parallels a host of others that have played lukewarm second banana to the billion-plus songs sold via the Apple-sanctioned iTunes Music Store: BuyMusic.com, RealNetworks Rhapsody, AOL Music Now, Musicmatch, Napster 2.0, Puretracks.

Even Wal-Mart is getting into the business, selling country singles at a lowball $0.88 per song. And in the online music world's most hilariously absurd fit of shark-jumping, Coca Cola introduced MyCokeMusic.com as one of the few download services available overseas.

Shea sees one major difference: Plan 9's downloads will launch into an already dedicated customer base. "There's the brand Plan 9, which has been going on for a quarter century now, and that has value within the region," he says.

What Plan 9 intends to offer is a universal system that will work with whatever hardware people have. "It should be accessible to the iPod environment and the Windows environment as well," Shea says. "There's an extra step to get it on your iPod, but that's okay."

But is it? The system Wilkes outlines would have an iPod owner copy and then create new files out of those purchases, a process called "transcoding," that critics claim degrades the already-compromised audio clarity of the files. But it's necessary because the store will rely on a format not supported by iPod: Windows Media Audio [WMA].

WMA has become a popular choice among online music sellers because of the ease with which copy protection can be added to the files, making them useless the moment a buyer sends them to a friend on a file-sharing network– or, more importantly, to 30 million friends.

And in a 20-year overdue fit of payback, Apple has refused to open its now-dominant musical systems to the Microsoft-championed WMA. The other online retailers all use Windows Media, and none of them are doing particularly well.

After three years in business, Apple now sells more music than Tower Records and holds about 80 percent of the legal downloading market with its iTunes Music Store. Still, the Store began turning a profit only in the final quarter of 2005. Before that, it had existed for the sole purpose of serving as a link in Apple's emusic monopoly.

Steve Jobs and company have aggressively locked users into its trinity: iPod, iTunes, and Apple's 99-cents-a-track Store. Each begets the next, and eventually buyers find themselves back at the beginning, buying or downloading whichever product started the cycle.

Late last year, label executives and industry lobbyists demanded– backed by their threat to withdraw rights to their music– that Apple allow tiered pricing. Apple stood firm, and eventually the labels caved, choosing to renew their loathed 99-cent contracts rather than risk alienating 80 percent of the download market.

At the height of the standoff, albums distributed by EMI and Sony/BMG began trickling out with embedded copy protection designed to prevent the music from being transferred to computers in any format playable by the iPod. Among these were several albums by artists affiliated with Charlottesville-based ATO Records and Red Light Management– including Dave Matthews Band, the North-Mississippi Allstars, My Morning Jacket, and David Gray.

By October, news broke that some of these discs– specifically those distributed through Sony/BMG– installed a nefarious virus-like bit of digital nastiness called a "rootkit" which posed a grave threat to the computer's security. PCs began crashing, CDs were recalled worldwide, and Sony/BMG lost a class action lawsuit. Trey Anastasio's album release was hastily scaled back because of the defective discs.

"Neither we nor our artists ever gave permission for the use of this technology," reads a tersely worded message on the ATO website. "Wherever it is our decision, we will forego use of copy-protection, just as we have in the past." Farther on, that same message includes instructions about how to defeat the copy protection. And there's an apology to customers.

Novelty item?

UVA ethicist Moreno has long been saying that online music sales are the wave of the music industry's future. "The album," he says, "will be a novelty item."

That's just what recent UVA graduate Ben Martin fears. "My computer crashed one summer," he says, "so I'm really paranoid about spending a lot of money downloading songs for a dollar apiece, and then losing them a few months later when my computer crashes again."

Even before his crash, Martin considered himself a fan of the liner notes and solid plastic of compact discs and found his iPod daunting.

"Do the math," Apple once bragged of its larger-capacity iPod. "That's four weeks of music– played continuously, 24/7– or one new song a day for the next 27 years."

"It can be overwhelming when you have thousands of songs in your hand and can't decide what to listen to," Martin says.

Clearly, not everyone is thrilled with the new music technology.

"It's a shame," says recent UVA graduate Jim Warnock. "Creating mixes from iTunes makes the rest of the artist's repertoire unimportant. That's what file sharing has done to people's mentality– created fans of only top hits."

Martin, however, disagrees. "Top 40 radio isn't all that bad," he says. "In some instances, the top hits are genuinely good songs, such as Outkast's 'Hey Ya!' iTunes is just another way of spreading good music, just like the old Napster and Kazaa were."

Although Napster– shut down by court order not so long ago– has rebuilt itself as a subscription-based download center that the RIAA now embraces, Martin sees problems for the industry.

"There are a lot of other alternative file-sharing programs that are totally free, and those are gaining popularity because they're a lot harder for the RIAA to track," he says. "Computer whizzes are geniuses when it comes to staying ahead of big companies like Apple and the RIAA, so there will always be free options out there."

Other suspects

It's not just legal and illegal downloading that have affected the music business. Albemarle-based musician Peter Griesar identifies video games as a major culprit.

"Music downloads," says Griesar, "have nothing to do with the industry woes– that's a lie perpetrated by the industry."

Griesar notes that video games, now a $10 billion a year business, have stolen much of the potential growth from music and movies.

"What's driving people to copy music is that it's too expensive," says Griesar. "They have a limited amount of money to spend on entertainment."

UVA alum Martin thinks downloading may ultimately help the industry and artists– if the downloader is an avid CD collector.

"I'm a perfect example of this," he continues. "I've discovered dozens of bands and bought their CDs simply through file sharing. And there's no way I would have spent money on those bands had it not been for Kazaa."

So what does all this mean for Cal Glattfelder and his little musical alcove on Water Street? Well, there are some who would say that shoppers should get there while they still can... the irony being, of course, that if enough people do, Sidetracks won't be going anywhere.

Shifting gears: Nielsen SoundScan figures released July 7 indicate that U.S. album sales fell 4.2 percent in the first half of the year, while legal downloads– with sales primarily from the iTunes Music Store– soared 77 percent. In April, "Crazy," a song by UK duo Gnarls Barkley, spent nine weeks at Britain's #1 single, the first chart-topper released solely as a download.

STOCK PHOTO

"The big issue with me is seeing the death of the hangout," says Plan 9's Danny Shea. "If people are migrating toward doing it on a computer, they're not interacting with a human being."

"

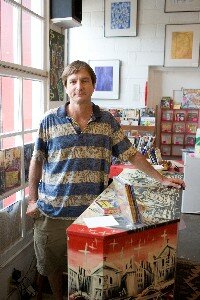

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

"Independent music retail is a low-margin business," says Cal Glattfelder, "but it can work here. There are a lot of people in this town who enjoy and are involved in music."

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

SIDEBAR- Apple bites: How local bands get rolling online

Since iTunes is rapidly establishing itself as über distributor with a blanket policy against dealing directly with artists, one has to wonder how smaller, breaking artists will be able to keep up. A cross-reference between the iTunes library and the Hook's directory of local musicians turns up a number of matches.

Devon Sproule and Clare Quilty got in through their record labels, but All of Fifteen, Sparky's Flaw, and several others have been able to get into the iTunes rotation through independent brokers like CDBaby and Tunecore.

These companies shave a little off the top in exchange for their services as intermediary. CDBaby takes 9 percent after Apple takes its bite, leaving artists with about 55 cents on the dollar; Tunecore charges a dollar for each song's delivery to each download store and an $8 yearly maintenance fee, after which 100 percent of the proceeds go to the artist.

Mike Meadows, lead singer and songwriter for the now-defunct Small Town Workers, offered that band's catalog for sale on iTunes by way of TheOrchard.com. "You pay them a small fee to license your music, and they put you everywhere: iTunes, eMusic, MusicNow, and all these other places," says Meadows, listing a few more of those second-banana sites. "It was very worthwhile."

King Wilkie is another local band dabbling in downloads. They were excited when their former label, Rebel Records, finally managed to get into iTunes with an older release, but the band soon found that download sales weren't ending up in their pocket– their contract allowed the label to keep the proceeds in order to recoup the costs of the album.

"We haven't seen a dime of it yet," says King Wilkie manager Rick Easton. "iTunes on a per-track basis ends up going through record labels and middlemen, and everyone takes a cut along the way. By the time it gets back to the band, we're talking pennies on the dollar."

Seeking an alternative, King Wilkie discovered the independent download services provided by MusicToday, the Crozet-based company owned by Dave Matthews Band manager Coran Capshaw. MusicToday treats download sales much like merchandise: proceeds can be routed to the artist instead of through a label if contracts allow it. Easton reports that 70 percent of the purchase price now reaches the band.

"MusicToday is a much more favorable deal to us," says Easton. And, it would seem, for customers, who seem to be biting. "MusicToday has been about 30 percent higher than through iTunes," he continues. "The only problem with the service that they provide– allowing us to sell direct– is that because of the nature of charging, we can't sell individual tracks. We have to sell the whole thing."

As the director of merchandise at MusicToday, Jim Kingdon oversees the sale of music downloads and can shed some light into that.

"The greatest cost in the single song download space is the transaction cost in executing the order, the credit card transaction fees," says Kingdon."When you factor in the record label and the processing cost, there's nothing left. If a meaningful solution can be implemented to solve the credit card transaction problem, you'll see a lot more download providers."

There's one last problem. In order to make the files iPod-compatible, MusicToday's method has to forego all copy protection. But that's okay with Easton. "If somebody wants it, there's always a way to get around it," he says. "It's kind of like closing the barn door after the horse already got out."

Kingdon sees a pattern developing. "The content that the artists have control over is generally sold as an unrestricted MP3, and the content that the record labels have control of is sold as a controlled file," he says. "In our case, it's very clear-cut that the artists we work with have chosen to offer their music up in an open format."

Plan 9 manager Kelly Wilkes sees the same trend and says that the Plan 9 store will offer unprotected MP3s in addition to the protected WMA files. But the former will most likely be limited to releases by independent artists and smaller labels.

"The ultimate goal here is to make sure that fans have the ability to buy music as readily as possible, so that they can act on impulse and their interest in the artist," Kingdon says. "The better Apple and MusicToday are at making sure that fans can act on that impulse, the better off everyone is, because more music will get purchased."

In all, downloads are really a hot-button issue for King Wilkie, who are currently between record contracts. "That's been a factor in our current negotiations– we're trying to get with a label that has been up to date and is doing some exciting things digitally," says band manager Easton.

It would appear, then, that King Wilkie is the local king of progressive music distribution.

But wait! Miljenko Matijevic, who is currently gearing up for the second revival of his 1980s rock band Steelheart in as many decades, can do them one better: he sells the MP3s himself, with no middleman whatsoever.

"Most artists can do this," he says. "It just takes a lot of time and energy– you have to get an e-commerce account and a credit card account." It's a feature built into his web hosting package, which is provided by GoDaddy.com, the most popular domain name registrar in the world, and involves the familiar "shopping cart" analogy so prevalent in online retail.

Go, Steelheart!

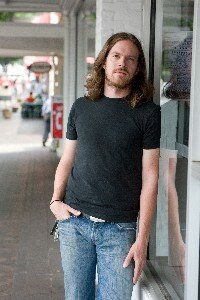

Mike Meadows' Small Town Workers may be gone, but iTunes keeps the music alive and the checks rolling in.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

"The ultimate goal here," says MusicToday's Jim Kingdon, "is to make sure that fans have the ability to buy music as readily as possible, so that they can act on impulse and their interest in the artist."

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

#