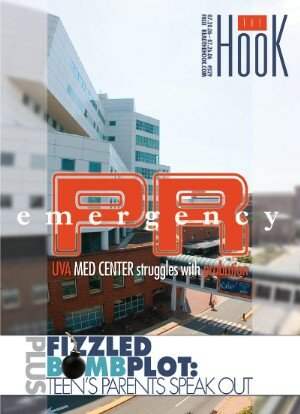

COVER- PR emergency: UVA Med Center struggles with probation

When Christopher Reeve broke his neck in a 1995 riding accident in Culpeper, UVA Medical Center basked in international acclaim as the hospital that saved Superman. More than a decade later, however, the lauded institution may be facing the hospital version of Kryptonite.

In April, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education– the national body that certifies all American teaching hospitals– placed UVA on probation for violations in the operation of its medical residency program. The designation could threaten the Center's ability to attract top applicants and, perhaps, to retain some of the world renowned experts who teach them.

The stinging blow to the Medical Center, which has publicly boasted "Top 100" hospital status for seven of the past eight years on a banner hanging from a pedestrian bridge over JPA, comes at the same time that the hospital's rankings in U.S. News and World Report's list of "America's Best Hospitals" have slipped. In 2004, the hospital received top rankings in 10 departments. In 2005, that number fell to seven. And in the 2006 report, released this month, only five departments made the grade.

The probation and slipping ratings combined, says one senior surgeon who requests anonymity, "doesn't paint a pretty picture."

Another senior physician uses harsher terms when asked about the Council's August 1 site visit that may determine the Medical Center's future.

"If we don't get off probation," he says, "we've gone to Armageddon for the hospital."

Hard knock life

It's no secret that medical residents work long hours– TV shows like ER and Grey's Anatomy portray their protagonists as bleary eyed and almost too exhausted to sleep... with their colleagues. But the reality of life during the three or more years of medical residency– a period when doctors learn their specialties under the watchful eyes of experienced physicians– may be far more brutal than even TV suggests. And it's no easier at UVA.

"I have worked many 100-plus hour weeks," says one UVA resident who spoke with the Hook on condition of anonymity. The resident says the probation didn't come as a surprise to him or his fellow residents.

The Accrediting Council enacted complicated rules in 2003 limiting the hours a resident could work to 80 per week averaged over four weeks, and limiting the number of hours between shifts as well as the maximum time a resident can be "on call." But the resident says violations of those limits are routine. In addition, he reports that understaffing at a number of levels has led to other problems: delays receiving test results, particularly overnight when radiologists and lab technicians are off duty.

Other policies– such as a relatively recent decree that patients well enough to go home should be discharged by noon– put pressure on residents to complete non-medical tasks such as lining up transportation or scheduling follow-up appointments that the resident says could have more easily been completed by support staff. But the support staff, he says, is inadequate.

The hospital's top administrator, Medical Center CEO Ed Howell, confirms that many of the resident's complaints are included in the Council's probationary finding. Other problems Howell identifies: that security on "call room" doors (rooms where residents can sleep) was inadequate, and that the Medical Center hadn't properly scheduled an interim site visit with the Council between its official five-year inspections.

Howell points out that the Accreditation Council has long issued "departmental" accreditation to teaching hospitals, including to each of UVA's 63 specialties. And it's no secret that many other schools have experienced problems with that type of accreditation, including Johns Hopkins, whose prestigious internal medicine program was placed on probation in 2004 over resident work-hour violations.

However, accreditation for the "sponsoring institution" is a new policy, begun just last July, and while UVA is the only school now on institutional probation, it's also among the first schools to undergo such a review. Forty-nine medical centers (of approximately 430) were reviewed during the first round in October, says Council spokesperson John Nylen. Of those, UVA and three others were "considered" for probation, Nylen adds. Each was given an opportunity to appeal probation before a final determination was made. The appeals succeeded for three, but UVA's appeal failed, and the probation was made final in April.

While Howell admits UVA needed to remedy the identified problems, he wonders whether other top teaching hospitals might be facing a similiar situation in coming months as more hospitals undergo the accreditation review for the first time.

"We may be the canary in the coal mine," he says.

Ironically, Howell may have even more reason to be frustrated by the rebuke than the physicians who work under him: he served on the board of the Accreditation Council for eight years until he left his post in 2003, a year after arriving at UVA– and the same year the Council enacted the new rules that Howell, as chairman of the board, helped to write.

While he now expresses optimism that the problems are being addressed, he acknowledges the gravity of the situation.

"I take this very seriously," he says. "I'm determined to resolve the problem."

Howell he does it

In the few years leading up to Howell's 2001 hire, national attention focused on improving the financial performance of teaching hospitals around the country, says UVA spokesperson Carol Wood. UVA's Medical Center was no different.

Howell, she explains, was brought in "to help put the health system on solid footing."

Some academic communities discussed "separating the hospitals from their academic institutions or closing them down completely," Wood says. UVA decided "the health system was too important to the community and the University, and that instead of abandoning it, we should find ways to make it stronger."

Howell, she says, "has done that."

In fact, based on the hospital's Top 100 ranking by the hospital auditing firm Solucient– the source of the much-ballyhooed banner on JPA– the hospital has been a top financial performer since at least 1998. While the proclamation "Top 100" does measure certain elements of care– fewer-than-average patient complications and deaths, for example– the award is primarily financially driven, using data regarding wider profit margins, faster patient discharge, and increased patient volume.

As the senior physician puts it, "These are the hospitals that provide the most care for the least amount of money."

So it's not the same as an award just for outstanding service, but is a healthy profit margin a bad thing?

Howell points out that since the Medical Center is non-profit, excess income doesn't go to shareholders; it's plowed back into the hospital in the form of new programs and equipment, staff incentives, and capital projects such as building renovation and expansion.

Since he began, Howell says, 11 new clinical programs have been implemented, including neuro-oncology and robotic surgery. In addition, he says, he has worked to strengthen the ties between the hospital and the schools of medicine and nursing and has overseen the renovation of an aging hospital building into a state-of-the-art cardiac care center.

"The end goal is patient care," says Howell, who started his career as a high school teacher and who defends himself against charges that his main focus is the bottom line.

"All of my values are of an educator," he says, pointing out that he still teaches several graduate-level courses.

The senior physician who spoke to the Hook says he doesn't agree with many of Howell's business decisions, but he also comes to Howell's defense.

"He's a bright and interesting guy," he says, adding that he believes that upon his hire, "Howell was given a mandate, in all fairness to him, to make a profit that was completely unrealistic for a teaching hospital."

That profit, Howell confirms, is in excess of five percent, up from the two-to-four percent the hospital had been making before his arrival.

As an example, Howell says that last year the Medical Center's "operating margin" was $42 million. He says the Center was able to purchase $63 million in equipment for the hospital by utilizing funds, depreciation, and interest earnings.

The physician agrees that having extra money to invest is a good thing; but the problem is that, "The people know these profits are made on their backs." The Medical Center has put pressure on the doctors, nurses, and residents, the physician says, "by asking them to cut corners, overworking them, stretching them in a way they don't feel comfortable."

What of morale?

"The reason we're in academic medicine is primarily to train residents, so it follows that the residency program is vital to our personal objectives," says the surgeon. "The fact that the institution is on probation is an enormous embarrassment and a black eye for the whole university."

That embarrassment could be part of the reason why trying to find on-the-record sources inside UVA Medical Center is a bit like looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack. Numerous chiefs of departments did not return the Hook's calls. But there's another possibility for their reticence: fear.

"I could lose my job," says the physician, while the surgeon also stresses the fear he feels that the administration could visit retribution on those who speak out. The real story, the surgeon says, is "how concerned people are that they'll be fired for speaking frankly."

Both the surgeon and the physician say they have received specific emailed instruction from the University directing that they not mention their UVA affiliation when talking to the press unless they have prior permission from the administration.

The feeling that their opinions don't matter and are not permitted to be voiced contributes to what the surgeon calls "a horrendous morale problem."

Wood denies knowledge of such an email, and Howell denies he has ever instructed Medical Center staff to remain mum with the press. He adds that he's unaware of any acts of administrative retribution during his tenure. "I don't try to be intimidating," he says. What he has tried to do, he explains, is to create an environment in which staff are free to approach the administration. To that end, he has commenced a series of open meetings to address any concerns about the probation or other issues at the hospital.

But despite these efforts, one prominent local businessman with an insider's view of the Medical Center says he also remains concerned about morale. As a member of both UVA's Board of Visitors and the Medical Center Operating Board until spring 2005, Bill Crutchfield says he is aware of a "perception that the culture of UVA's Health System has gone astray."

Crutchfield defends the Board of Visitors against charges he has heard that it is "singularly focused on achieving a high operating margin." While he doesn't believe that is the case, he admits that "the organizational culture of the institution may now be rooted in this erroneous premise."

The solution, Crutchfield believes, may be found by implementing strategies he says he uses in his eponymous electronics company headquartered in Charlottesville.

"UVA Health System should define, inculcate, and manage a rich organizational culture that obsessively focuses on its patients, employees, and partners," he says. If it does so, "Strong operating margins will follow," he says. "But more importantly, it will become an even finer institution and an even greater asset to our community."

The physician agrees with Crutchfield's assessment. "We have to break even and make some profit to reinvest in our infrastructure," he says, "but we don't have to do it at the expense of killing the quality and the compassionate nature of the work."

What's next?

As the next site visit looms, Howell says the Medical Center is actively working to fix problems and strengthen its residency program.

Among the improvements: new locks have been installed on the call room doors, all documentation in the Office of Graduate Medical Education has been updated, and new staff has been hired– support staff to assist residents with the discharge process as well as additional ultrasonographers so that ultrasounds may be read more quickly, slow readings being one of the resident's complaints. Also, chiefs of departments must crack down on resident work hours, something the physician believes wasn't happening in some departments before the probation.

When it learned of the probation in April, Howell says, the Medical Center also made changes in its Office of Graduate Medical Education. A renovation of the actual office space is under way, the residents' fitness facility is expanding, and a new head of the Graduate Medical Education office, endocrinologist Susan Kirk, was brought in to guide the program back to full accreditation.

"We've been soliciting the residents' input," says Kirk, "both directly and confidentially."

The resident who spoke with the Hook says he believes Kirk is working hard to address the issues.

Kirk praises Howell's "very strong commitment to the residents and the hospital," and, like Howell, she is optimistic that the probation will be lifted sometime after the August 1 site visit.

Howell agrees it's "absolutely" critical for the Medical Center to succeed in that mission to fulfill the institution's two most important goals: making UVA "the most sought-after place to pursue a clinical career, and the most sought-after place to complete a residency."

"We're going to do anything and everything," he says, "to do what's required."

Armageddon just might be riding on it.

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

UVA Vice President and Medical Center CEO Ed Howell

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

New banners hanging in the main hospital entrance tout staff as "Everyday heroes." It's a way, says Medical Center CEO Ed Howell, for the hospital to show appreciation.

PHOTO BY COURTENEY STUART

#