ONARCHITECTURE- Critta's corner: Design, history, sway development

At first glance, the recently approved 700+ unit development off Rio Road appears to be yet another example of suburban sprawl, of developers cashing in on Charlottesville's popularity, building expensive houses in exclusive communities and adding yet more cars to already clogged roadways. Do we really need another Dunlora right next to Dunlora?

Give "Belvedere" a second look, however, and things aren't quite as they appear. In fact, if all goes according to the developer's latest plans for the 207-acre property, Belvedere could be a model for the future of suburban housing, as well as the preservation of slavery's past history.

"We want this to be a flagship project, not just for us, but for the whole county," says Chris Schooley, director of land development for Stonehaus Inc., Belvedere's developer. Sounding as much like a born-again new urbanist as a developer, Schooley says Belvedere could be a shining example of a mixed-use, walkable community.

"The county's Neighborhood Model is well-intentioned, but you still need responsible design to make it work," he says. "We're trying to prove that we're going to build what we say we're going to build."

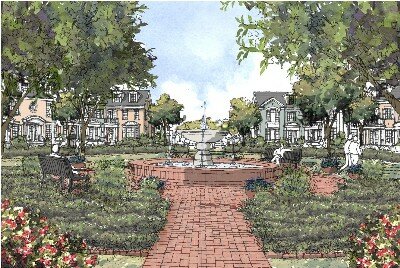

What Stonehaus says it will build is a dense, walkable "village" with preservation areas, public parks, a private school, a commercial center, and a public village green at its core. In addition, Stonehaus hopes to add "carriage houses" that owners can rent out to help pay the mortgage. Instead of monolithic houses on large lots like Dunlora across the street (which Stonehaus also developed), Belvedere might become a "living being, an organism that will function as a system," according to its vision statement.

"This kind of green urbanism ties everything together," Schooley says, "integrating the land with the built environment."

The vision statement mentions roof-top rainwater collectors, Energy Star certified construction, wind-powered electricity, and site orientations that take advantage of the sun, among many other green amenities. But why stop there?

Belvedere's developers hope to encourage positive living by "developing physical opportunities to promote healthy living through exercise, nutrition and spirituality." Add a concern for child safety, the handicapped, and middle-class folks on a tight budget– not to mention recycling and the history and ecology of the Belvedere site, and you've got a vision to make a new urbanist weep for joy. Not to mention one sweet sales pitch.

To put its philosophy into action, Stonehaus has teamed up with the Charlottesville Community Design Center to sponsor a design competition for Belvedere's civic core. In July, eight architects will be chosen by Stonehaus. Then, in August, a jury– including several prominent architects as well as Charlotesville's mayor and the chair of the Albemarle supervisors– will select three finalists to be interviewed for the job. While Stonehaus may deserve praise for adopting such progressive ideas, its moves toward stewardship of land and history appear to have come only after some prodding.

For example, after Belvedere was first proposed in 2003, the Albemarle County Planning Commission repeatedly turned down its rezoning requests, citing a host of design and engineering problems. By June 2005, there were still 11 problems, including the lack of affordable housing, conflicts between the development plan and graphic representations, right-of-way issues with other land owners, and concerns about land preservation.

Stonehaus appeared exasperated with the hurdles. At a June 2005 meeting, then project manager Don Skelly told Planning Commissioners that his wife "could have had two children in the time that it has taken to approve this project, assuming it gets approved," according to the minutes.

In addition, the Commission was pushing for a more commercial, walkable center for the development at the time– an idea that Stonehaus had resisted, a former planning commissioner remembers.

Schooley– who was not working for Stonehaus at the time– admits that the company's approach has evolved. While the company initially sought a "clubhouse" model similar to gated communities like Glenmore or Dunlora, it eventually chose the merits of the "village" model.

But one village failed to survive.

Preservationists and archeologists voiced concerns about the old Free State community– one of the earliest free black communities in the state– located on the Dunlora and Belvedere site. In fact, according the Jillian Galle, an archeologist at Monticello, Sally Hemings' sister Critta lived in Free State, and has a road named after her on the Belvedere site.

Unfortunately, much of the remains of Free State were demolished when Stonehaus completed its last addition to Dunlora, according to Aaron Wunsch, an officer with Preservation Piedmont. Wunsch and Galle, who are married, happened to be house-sitting for a friend at Dunlora when they took a walk and discovered some the remains of Free State, which included a stone-lined cellar hole, cellar impressions, standing stone chimney stacks, and several turn of the nineteenth-century houses, some of which had been occupied well into the 1940s.

"It's amazing," says Wunsch. "Just four years ago, the Free State settlement was still standing."

After discovering the remnants of the community, the Planning Commission asked developer Frank Stoner of Stonehaus to conduct an archaeological study on the site, which Stoner agreed to pay for. Still, plans for the addition to Dunlora went forward and the site was covered over. After that, Wunsch and Galle say that preservationists started making some noise about Stonehaus' plans for Belvedere, noise they believe contributed to the initial rezoning denial.

"The cultural landscape of the Free State community," Galle says, "was largely destroyed by the Dunlora development, and would have been completely obliterated by the Belvedere development."

"It was an interesting site," Wunsch says of the lost Free State remnants on the Dunlora site. "Stoner eventually did the right thing, but it was a disappointment to see it go." Still, Galle and Wunsch don't blame the loss as much on Stonehaus as on Albemarle County.

"Unfortunately, there's no mechanism in the County to red-flag this stuff," says Wunsch. "Eighteenth-century buildings have been taken down around the County in the last year, and nobody has noticed. You're largely depending on the goodwill of developers to save such places, because the County has no preservation code."

The folks at Stonehaus seem to have had pangs of conscience, as the new development plans for Belvedere call for further archeological studies and the preservation of a recently discovered cemetery, as well as the installation of an "interpretive historic kiosk" that will detail the Free State history.

That's all good news for UVA professor Scot French, interim director of the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies, which recently created a historical archive for the Proffit community, a recently recognized historic district along Proffit Road described as "a rare survivor of the black communities established in Albemarle County after the Civil War, but which have largely disappeared or been rebuilt."

"Acquisitions of property by those who were once property," says French, "that's a significant moment in history. At the very least, we need to document these buildings before we tear them down."

According to UVA library's historical census collection, there were more than 12,000 free slaves living in Albemarle County in 1860, which means there are still many of these sites scattered around. "We need to map these places before they are destroyed," French says.

According to Schooley, as soon as Stonehaus selects an architect, the company will break ground with a new road in the Fall, start the first house in the spring of 2007, and begin work on the civic core next summer.

"You see, not all developers are bad, evil people, " Schooley jokes, proud of his company's new emphasis on both history and new urbanism. "We're spending a lot of time thinking about the social aspects of this development."

Of course, they're also thinking about the bottom line. According to a recent article in Business 2.0 Magazine, these new "village" developments may be the next boom in real estate as a new generation of homeowners emerge. The article cites a study by the nonprofit Congress for New Urbanism that notes, "While less than 25 percent of middle-aged Americans are interested in living in dense areas, 53 percent of 24-34 year olds would choose to live in transit-rich, walkable neighborhoods if they had the choice."

In the end it appears that Stonehaus Inc.'s present commitment to "green urbanism" and historic preservation owes as much to the noisemakers as its own good will.

"We want this to be a flagship project, not just for us, but for the whole county," says Stonehaus Inc.'s Chris Schooley of the developer's "village" model plan for the Belvedere development.

Courtesy of Stonehaus Inc.

#