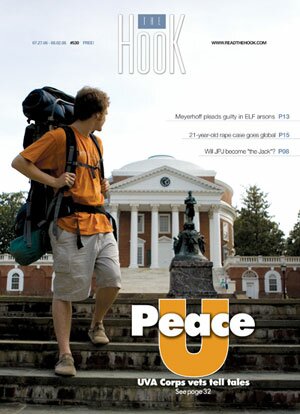

COVER- Peace U.: UVA Corps vets tell tales

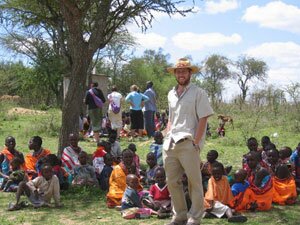

"I was feeling really negative about being in America, the war and the presidency, so I wanted to get out and see an alternative," says John Teschner. So the 2003 UVA grad did what UVA students have done more than any other comparable University graduates in the past five years: join the Peace Corps.

The foreign service organization, which turns 45 years old this year, was created by John F. Kennedy as a way of combating anti-American sentiment during the Cold War. In the 21st-century, the volunteers face a whole different set of world problems. Teschner, for instance, found himself in Kenya, asked to serve as an AIDS educator in a country where the destruction caused by the disease had been officially declared a national disaster four years earlier.

"A lot of money goes into Kenya to fight things like HIV, and a lot of it is wasted," he says, "Education and awareness are cheap."

Teschner lived and worked in a local high school, ostensibly to teach local teenagers how to minimize the risk of exposure to the virus. But that changed rather quickly.

"You can say what you need to say about HIV in about 10 minutes, really," he says. "By the end, I was teaching whatever the kids wanted to learn about."

Those expanded duties also included facilitating self-guided discussion about the disease among adults, many of whom were wary of educational attempts led by foreigners. "I wanted to minimize my presence there," Teschner says. "Getting people to talk about it was one of the best things I could do. It's not a culture where people are comfortable talking to each other about sex."

Ironically, Teschner's Kenyan experience ended up solidifying his approval of the America he had gone away to escape. "The government is a lot more high-functioning than we give it credit for," he says. "If you go to a place like Kenya and see how their government functions, you have a whole lot more appreciation for ours."

Since 2000, more than 400 UVA students have shown their appreciation for something by serving in the Peace Corps, and 80 of them are currently active. UVA has a historic tally of 838 graduate volunteers, and the Corps has drawn plenty of faculty and staff members from the Cavalier ranks.

In March, UVA President John Casteen hosted an evening of celebration honoring five decades of such volunteerism. Descending from a Rotunda staircase before an audience of veterans and greenhorns alike, Casteen shared his enthusiasm for the program as readily as he did his respect for those who keep it alive.

"Peace Corps volunteers serve our country in the cause of peace by the work they perform abroad, by living abroad, and by bringing back to this country the knowledge, the experience, the sympathies, and the beliefs they have acquired in the course of those years," he said.

Here are some of their stories.

"I have a history of the Peace Corps in my family," says 2003 UVA grad John Teschner. "Three of my uncles were in the Peace Corps, and my grandfather was a Peace Corps medical officer. Ever since I was five or six, I've seen myself in the Peace Corps."

COURTESEY JOHN TESCHNER

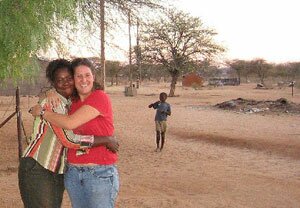

Tina Schuster

1999-2002

Otjiperongo, Namibia

<<>>

Like many other Peace Corps volunteers, Tina Schuster was was asked to be a teacher when she was posted, but there was a chilling undercurrent to the subjects she was assigned– English and AIDS education. "It wasn't ever stated, but for me the priority was really HIV/AIDS," she says. "The school wanted me to emphasize English, but the whole reason we were there was that we were replacing teachers who had died of AIDS."

The English curriculum was dominated by a government-mandated proficiency test administered at the end of the year. "They were very disadvantaged at our school," she says. "We had only one textbook, so I didn't really use a text. Out of all the kids I taught, maybe a handful of them would pass the test. I was just trying to get them to a level where they could communicate comfortably in English."

On the other hand, the students seemed to know a lot more about the HIV/AIDS education curriculum. In a way, that was the problem: "They were already well informed. I gave them a multiple choice test about HIV/AIDS, and they got everything right," she says. "That was the really frustrating thing. They just weren't practicing it."

That's why she had them create an educational musical theater production.

It was a rather flamboyant approach to a dark state of affairs. "It's thousands of years of a male-dominated culture, where there's a lot of extramarital sex and a lot of unprotected sex, and you can't force a man to use a condom," Schuster says. And while it's a bit unreasonable to expect one woman to turn the AIDS crisis around, Schuster's play certainly got their attention. "I don't know if they changed their behavior," she says, "but they were okay talking about it."

Since returning to the US, Schuster has continued with her teaching career. "When I came back, I went to get my teaching degree, and I knew I wanted to teach internationally again," she says. She has taught at Fluvanna County High School for the past three years, and is currently making plans to apply for work in the Dominican Republic.

"It was eye-opening. I felt like I was actually a part of something, a part of people's lives and making a difference," she says. "It made me want to keep moving around. My mom is not happy about that."

COURTESY TINA SCHUSTER

Tina Schuster

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

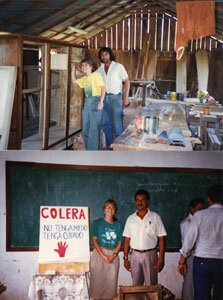

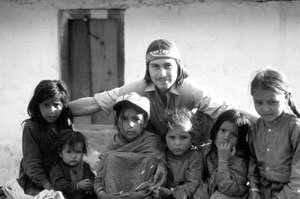

Kirsten Albert

1990-1992

Ca-aguazu, Paraguay

<<>>

It seems that, almost without exception, volunteers come back singing the praises of the Peace Corps. Kirsten Albert, however, takes that enthusiasm to a new level.

Her lifelong involvement with the Peace Corps began when she was five, when her parents took her trekking through South America. "My very first memory [of the Peace Corps] was meeting a volunteer who lived in this lovely little house in the jungle. That night, my bed was in the path of really big rats that made their way the same way every night and walked right over us. I thought it was my dad tucking me in and being silly."

Her own turn came in 1990, when as a new volunteer, she shipped off to Paraguay. Even though she had majored in Spanish and Latin American studies at UVA, Albert wasn't prepared for the linguistic and cultural challenges that awaited her there.

"It's one of the only countries in the world that honors the indigenous language by having two national languages, Spanish and Guarani," she says. "Since I had the Spanish, I had very intense Guarani training. It was a great opportunity to be the comic relief for the entire community by putting my foot in my mouth. In Paraguay, it's not considered polite to correct someone, so I just get these bursts of laughter."

Albert worked as a health education volunteer, a job of which the definition changed every day. "The tasks we did were so varied, such as creating better wood stoves that would cut down on childhood burns– to building better latrines or introducing toothbrushing techniques to cut down on cavities. Coca Cola being such a treat really has an impact on dental health," she recalls. "We were doing something different all the time in response to what the community wanted."

Sometimes, what the community wanted was a little upsetting for a displaced American. "It's very powerful to buy your groceries and then feel guilty about bringing them into town, and then trying to find ways to share them as much as possible," she says. "The excitement of buying powdered milk and bringing it back– and the guilt– is really something. Milk is such a luxury item. I'd often end up making milkshakes or drinks for kids in the area."

The Peace Corps limits volunteer terms to two years, so upon returning, Albert had no way to quench her thirst for the experience except by working in an administrative capacity at the Peace Corps headquarters.

"It's unlike any job I've ever been in. It's such a remarkable organization, from both sides," she says.

Unfortunately, the Peace Corps also limits administrative jobs to five years, after which employees must spend an equal amount of time away from the organization before they're allowed to return. Albert left in 2001.

"I've been measuring it; I have another year to go," she says. "It's very tempting."

COURTESY KIRSTEN ALBERT

Kirsten Albert

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

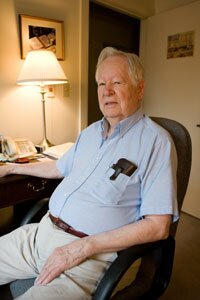

Merrill Peterson

1997

Yerevan, Armenia

<<"I'm 85 now, and in my career as an American historian, I'd never done anything like that before. The Peace Corps was the first big program offering American humanitarian relief.">>

Merrill Peterson isn't a typical Peace Corps volunteer. When, in 1997, he embarked on what he expected to be a two-year stint in Armenia, the well-known author was 79 years old. An expert on American history, particularly Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln, UVA professor emeritus of history Peterson expected to be posted to the National University of Armenia in Yerevan, the capital, where he hoped to create an American history and culture program.

Seven weeks into his tour, however, illness forced his return to the US. But that wasn't the end of the story of his fascination with Armenia.

"I had prepared myself on Armenia before I went," Peterson says, "particularly the 1916 Armenian genocide. When I returned, I began to do more research on the implications of genocide, and I decided I wanted to write something about it."

Peterson says that even during the short time in the country, his appreciation for Armenians grew. He calls Yerevan a "typical cosmopolitan European-style capital– attractive, with major thoroughfares– of three million people." He lived, however, with a family in a small town 20-25 miles from the city, where he hoped to improve his mastery of Armenian, a language he calls "very difficult" to learn. But his hopes were dashed because the family's young daughter was studying English and wanted their courtly house guest to help her practice by chatting in English.

Starving Armenians, the book that resulted from Peterson's experience, focuses on the relief efforts of a group called Near East Relief. Peterson calls the book a memoir as much as a history, since he takes the subject through the Armenian community in the US and traces their valuable contributions to American culture and society.

"I wouldn't have written the book without my Peace Corps experience," Peterson says, testimony to the lasting value of the experience, despite its premature ending.

COURTESY MERRILL PETERSON

Merrill Peterson

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Cliff Maxwell

1978-1981

Far Far Western Development Region, Nepal

<<<"Being isolated in Nepal, your psyche changes for the better. Self reliance is the biggest thing; everything else can be built on that.>>>

In the late '70s, Cliff Maxwell was worried that his chemistry degree was about to doom him to an oily post-collegiate experience. "The only jobs available in chemistry were with the oil companies," he laughs, "and I certainly didn't want to work for them."

A phone call from the Peace Corps informed him that he'd been accepted for a slot that had opened up at the last minute– if he could be ready to go in two weeks.

With his degree unfinished, Maxwell packed up and flew to Nepal, where he planned to earn his last two credits through an independent study project to be completed in conjunction with his science education position in the Peace Corps.

Oops.

"When I went to Nepal, I realized that there wasn't any science education there," he says. "We were it."

That had more than a little bit to do with his placement. Peace Corps volunteers are often considered adventurous by their boring and domestic friends, but even among other volunteers, Cliff Maxwell may have seemed like a bit of a daredevil– he specifically asked to be posted in the most mind-bogglingly remote regions of western Nepal.

"Nothing had been established out there, so the Peace Corps drove me out in a Jeep through northern India for six days. Then when the road ran out, it took 11 days to walk to my post," he says. "We were posted no closer than a day's walk from the nearest neighbor. When we got our checks, once every three months, it would take a week to walk to the bank and cash it."

Nevertheless, 400 Nepali children converged on the modest school every day for instruction. Maxwell taught six classes a day in a variety of subjects, some of which were more contextually appropriate than others.

"Teaching Ohm's Law of Electricity to a village that had no electricity, or using soapstone for chalk on mud spread on the wall for a blackboard was a challenge," he says

Something about the quaint charm of the village resonated with him, and when his service ended, he spent six months trekking through Thailand, Malaysia, and Australia before returning stateside.

"Ronald Reagan had been elected in 1980, and the Iran Hostage thing happened in 1979, so my perception was of the country becoming so much more conservative," he says. "The images of people picketing with signs saying 'Iranian Students Go Home' were just so narrow minded. I wrote to my family and said that I didn't want to live here anymore; I only came back in 1981 to explain to them why."

During that time, however, he realized that he also wasn't ready for the emotional stress of being a perpetual outsider. "I've been in reverse culture shock ever since. There was no place for me to go back to and fit in," he says. "I decided to stay here, where I could at least talk to people about what I was feeling."

And it must have buoyed his spirits somewhat to finally get his degree. "Evidently someone forged my signature in 1979, and I had a diploma waiting for me for a year and a half," Maxwell laughs. "They did end up waiving those credits."

COURTESY CLIFF MAXWELL

Cliff Maxwell

PHOTOS BY WILL WALKER

Charlotte Crystal

1977-1979

Sama, Mali

<<>>

With a degree in International Relations– with a specialization in developing countries– Charlotte Crystal was a dream come true for the Peace Corps, which promptly placed her in Mali to help bolster agricultural efforts. "I was very interested in Africa, so this was a great way for me to get some first-hand experience," she says.

But the experience was also a dream come true for Crystal. David Mattern, who is now her husband, was already there, having been stationed in the same village to work on related projects.

"He set everything up, and I pretty much just maintained it," she says.

The two of them hit it off and were married before returning to the U.S.

The projects they organized in Mali helped introduce vegetables and poultry to a tribe of fishermen who grew grain in the off-season.

"When I left, there were probably 20 women with vegetable gardens who hadn't done that before," she says. "While they did put some into their household soup pots, more of them would go sell them at a local market and use the money to buy stuff. The main impact of the vegetable project wasn't what we had hoped, but it had the effect of improving their standard of living."

That's okay: after all, unintended benefits are still benefits. In fact, Crystal's very presence had an important side effect. "People saw a white woman living alone and doing something other than being a housewife," she says.

It was that model that may have made the biggest difference– at least in the life of one little girl. "There were only 20 kids in the town who went to school, and only two of them were girls. One of those was the daughter of Yaya, a man I worked very closely with," says Crystal. "I think that from my example, the family thought it was worthwhile to send her to school."

These days, Crystal does public relations work for UVA, but she still can't shake her lingering interest in Mali. "I would like to go back at some point," she says. "My husband and I have a 12-year-old son, and we're thinking about taking him back so he can visit, and we can see if there's any residual benefit 30 years later."

COURTESY CHARLOTTE CRYSTAL

Charlotte Crystal

Charlotte Crystal

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Larry Eicher

1964-1966

Turkey

<<>>

Larry Eicher's entire future was born on a Dallas street on November 23, 1963. Once President Kennedy died, the stirring call to "ask what you can do for your country" began to resonate much more intensely, and Eicher quickly signed up for the fledgling service organization that had been Kennedy's pet project since the start of the election campaign.

If it was Kennedy who laid the foundation for the Peace Corps with executive order 10924 in 1961, it was Eicher and the crew of 1964 who built the frame– they were among the very first Peace Corps volunteers, and as such set the course the organization would follow in the years to come.

"Mine was one of the earliest groups going over there," he says. "Part of the problem was figuring out what one could do" in Turkey, where he was assigned. "We spoke English, so we became English teachers."

It would be an understatement to say that they were sorely needed. "By Turkish standards, if you don't have a teacher, you automatically pass," he explains. Scores of schoolchildren were socially promoted by default only to be wrecked when they ultimately faced a curriculum that would often assume two or three years of experience.

Like many other Peace Corps volunteers– and many teachers in the U.S., for that matter– Eicher quickly jettisoned the methods he had expected to use in teaching for the standardized tests. "Kids were just learning the questions– kind of like the Standards of Learning today," he says, "so we just threw it out and developed our own.

"It wasn't a pleasant meeting with the Ministry of Education," he recalls. "Now that I'm retired, I realize in retrospect that it might have been a bit smarter to do it a little more diplomatically."

Eicher spent 30 years in the foreign service, during which time he was sent abroad as a health development officer with the backing of the U.S. foreign aid program

"In 1964-1966 I lived on a dirt road in a two-story apartment building that had just been built. That was 'modern,'" he says. "When we went back, we returned to the site of my apartment, and it was a four-lane dual carriageway. Lining the streets were 10-, 12-, and 15-story apartment buildings, and my little apartment building was long gone. Down the street was a modern movie theater. All those things weren't there in 1964 and 1966. It's amazing."

COURTESY LARRY EICHER

Larry Eicher

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Janna Olson Gies

Philippines

1968-1970

<<< I've gotten three jobs in my life because of my Peace Corps experience.>>>

Janna Gies' Peace Corps service cost her a day of her life. As a student in education at Hameline University in St. Paul, Minnesota in the late '60s, she, like other idealistic college students in America at the time, was eager to make a difference in the world.

"Senator Hubert Humphrey was pushing it after JFK's death," she says, "and he was from Minnesota. It seemed like it would be a great way to see the world."

When her application was accepted, she was assigned to the Philippines. The assignment and the timing were perfect for Gies, who had recently married, so the couple flew to Hawaii for three months of training.

They lived and taught in the small Philippine village of Bangued in the Abra province. If living in a village without electricity, phones, and running water was difficult, teaching without books was even harder. So they set about establishing a library.

With the aid of her parents, who solicited donations back home in Minnesota, the couple were able to acquire 10,000 books for the town. "My dad arranged to have them shipped through a Navy program called Operation Handclasp," she explains. People in the village helped with the construction.

That impact appears permanent. "I looked not too long ago on a map," Gies says, "and saw the library is still there."

Living in another culture for real and learning about what they could do to help people in a Third World country was easily the best thing about her experience, Gies says. "At the time we were in the Philippines, there were 900 volunteers, and now there are none," she explains.

And while the political instability there today is a problem, the real reason there are no volunteers is not a problem at all. "We had volunteers there in the '60s, and '70s, and '80s, and they did a good job," she says. "So now they send volunteers to other countries that can still use our help. That was one of the countries we moved into and really did a lot."

Gies has mostly good memories of her experience, although she does recall the hardships such as heat and remoteness. When a cat they had adopted needed rabies shots, they had to get the vaccine by mail and administer it themselves because the local veterinarian would not treat domestic pets.

Isolation was also problem, but at Christmas and during school vacation times, the volunteers gathered for conferences and socializing, experiences that often led to life-long friendships.

When their enlistment was over, the couple came home the long way, through Southeast Asia and Europe. Today the former volunteer is now the office and business manager of the Virginia Quarterly Review and has dreams of traveling with her second husband, David Gies, director of UVA's new Semester at Sea program. This time they'll go east.

"We started in Hawaii and went west," Gies laughs. "I went around the world and lost a day of my life. My dream is to get it back."

COURTESY LARRY EICHER

Janna Gies

PHOTO BY WILL WALKER

Vijith Assar is the Hook's music editor, and Rosalind Warfield-Brown is the culture, real estate, and copy editor.

#