FACETIME- Pill cure? UVA doc sees Mel's fix

Two years ago, Dr. Bankole (pronounced bank-o-lay) Johnson, the 46-year-old chair of UVA's department of psychiatric medicine, turned down an interview request from Playboy. "At the time," he laughs, "I was worried about the impression it would make. But now I think it might be a good idea. We might get more patients."

Indeed, Johnson's bold comments about such sexy research— that a pill could cure alcoholism— have attracted attention, particularly recent interviews in which Johnson seemed to give a pass to anti-Semitic spewer Mel Gibson.

Alcoholics "don't understand what they're saying," Johnson was quoted in the L.A. Times, "and they don't mean what they're saying."

But in the same article, another neurobiologist argued, "Alcohol doesn't create the ability to say things like 'Jews are controlling the world.'"

Is it the alcohol talking, or the alcoholic? That's a question Johnson hopes to answer.

***

"My path to America was very odd," says Johnson in a proper British accent, sitting behind a big bowl of gourmet chocolates and sipping coffee in his UVA office.

Born in Nigeria and educated in Britain, the addiction expert was invited to the U.S. in the late 1980s during Nancy Reagan's "Just Say No" campaign. The popular and often satirized anti-drug initiative ended with Bill Clinton's election, but Johnson decided to stay, accepting a position at the University of Texas in Houston to pursue the challenge he had set for himself as a British doctoral student: finding a pharmaceutical cure for alcoholism.

Ironically, considering the cause that brought him to America, Johnson says people just can't say no to drugs, that brain processes are too powerful and too natural to resist.

"Without the potential for addiction, there would be no potential for survival," says Johnson. "The same pathways important for addiction are the same for maintaining survival by promoting feeding, sexual behavior, and learning."

Johnson, who came to UVA two years ago, says that humans, rats, and even flies show similar behaviors and withdrawal symptoms– all animals are susceptible to addiction. "It must have been implanted there by the creator for a vital purpose," he says.

While Johnson hasn't figured out the purpose, he has shown ways to reduce the cravings. Researching a drug called topiramate, Johnson discovered that people who took the drug were six times more likely to quit drinking than those receiving a placebo. He's also studying ondansetron, which reduces cocaine dependence. Next up? A study on that scourge of the Blue Ridge: methamphetamine.

Obviously, Johnson's research challenges the abstinence approach characterized by "Just Say No" and Alcoholics Anonymous. And while he doesn't dismiss such programs, he thinks they could be more efficient.

"There's no evidence that big therapy is much better than little therapy," he says, wondering why "talk therapy"– the backbone of psychological counseling– couldn't be shorter, more focused, and calibrated for effectiveness the way drugs are.

If Johnson's drug research is successful, might the 12 steps that recovering addicts have been negotiating for decades become a footnote in medical history?

"Cravings are just part it," says Phoebe Fliokas, a substance abuse counselor with Blue Ridge First Step. "We've had alcoholics relapse who didn't have cravings. It's about changing life patterns and learning new behaviors."

Fliokas says she favors new drugs to fight addiction, but thinks an integrative approach is necessary. "We've found that programs like AA and NA work best for people who go through here... in terms of relapsing."

For Johnson, however, relapses will be prevented when the need for the drug is eliminated, and he foresees a day when research yields a vaccine for alcohol, cocaine, and cigarette addiction. "It would make these destructive drugs useless," he says, "because it would stop the pleasure it gives to the brain."

Speaking of pleasure, what's with the big bowl of chocolates?

Johnson laughs. "I want to make sure that everyone who comes to my office leaves with a sweet experience," he says. "Besides, this is the only legal mood enhancer I can offer at the University."

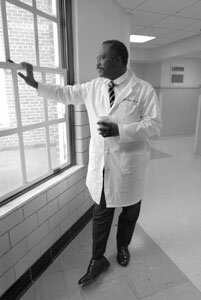

Dr. Bankole Johnson

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#