COVER- Rockumentary spotlights dance-rock legends

The rockumentary has a long and storied history as the sublime art form created by symbiosis of the two most glamorous forms of modern media. Soon, Charlottesville will have its own place between the stage antics of the Talking Heads in Stop Making Sense and the bumbling British metalheads from This Is Spinal Tap. Scheduled to premiere at the Virginia Film Festival this fall is Live from... the Hook, a film documentary chronicling the vibrant Charlottesville music scene of years gone by, and focusing on... well, you know...

Guess again, smartypants.

Actually, the film zeroes in on the rock bands of the 1980s and tells their stories through the eyes of Charlie Pastorfield and Bob Girard, two local musical evergreens who played in most of the groups that mattered.

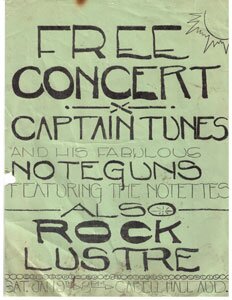

"It's a three-act structure," explains producer Andy Herz. "The first act is essentially 1970-1977. It talks about the music scene at the time of the Vietnam War: the Charlottesville Blues All-Stars and the Hawaiians and Captain Tunes. The second act is the heyday of Easters and Skip Castro and Johnny Sportcoat and the Casuals, when those bands were phenomenally popular up and down the entire east coast. The third act is more recent years, featuring bands like Indecision and especially Dave Matthews."

"For me, it's kind of a labor of love," says director Joe Grafmuller. He was at UVA in the 1980s and watched Girard and Pastorfield bop their way through several locally and regionally notorious bands, including Pastorfield's Skip Castro Band and Girard in the title role in Johnny Sportcoat and the Casuals.

It's the same story with the rest of the crew: "Everyone who's working on this– with maybe one exception– has a direct connection to Charlottesville, and the one exception is thinking of moving there," says Herz. "A lot of us were students at UVA and were at fraternities, and the others are long-time local residents who've known these guys for years."

So what's with the name? It has nothing to do with the newspaper, the Hook, and everything to do with the city so lovingly called Charlottesville, also called the Hook.

"They call it the Hook because people just want to stay there," Skip Castro's wild-haired, wild-keyboarding Danny Beirne tells the film crew.

David Ibbeken of the band Indecision also knows the feeling. "When you go away and you start to feel the draw," Ibbeken says in the film, "then you start to understand where the term comes from."

The film project came together on January 28 at the grand opening of Crozet's newest music venue, Uncle Charlie's. The celebration hosted by owner Charlie Mayer featured music by the Gladstones, a band that includes both Girard and Pastorfield.

Herz had already been thinking about making a movie based on music in Charlottesville. Seeing the two icons from his youth again that night in Crozet was such a headrush for the 1984 UVA grad that he immediately approached them about participating.

Now a Brooklyn-based entertainment and technology lawyer, Herz was the editor of the now defunct University Journal in his final year at UVA, a member of the Fiji fraternity, and an avid band-goer.

"We just thought he was a complete lunatic," says Pastorfield. "Well, he is a complete lunatic, but he kept calling us after that, and slowly we started realizing that he was serious."

Girard may not have been as shocked. "I think it's a neat story," he says. "Charlie's a really compelling guy, he has friends everywhere. And I don't think I have a lot of enemies. Between us we know a lot of people and have been through a lot."

Al Hinton now books music at Uncle Charlie's, but 25 years ago he was at UVA watching Pastorfield and Girard, just like Herz and all the others. Word of the project reached him that night at the party.

"A couple of Andy's Fiji brothers said that we should document that period, because it was really something special," says Hinton. "I was thinking to myself that every college kid probably thinks that, but the more we talked about it, the more we realized that it really truly was."

The reason for all the enthusiasm? Gratitude.

"I learned a tremendous amount of what I know about music from Skip Castro and the Casuals," says Herz. "I had never heard anything like it. Like so many of us, I had been brought up on Boston and Kansas and Molly Hatchet and Lynyrd Skynyrd. That's how I began a musical education that I've tried to never let go of."

Producer Grafmuller experienced a similar awakening. "The clubs in Northern Virginia were mostly heavy metal," he says. "Then I went to UVA, and my eyes were wide open– all this great blues and roots rock music. They were phenomenal musicians. It was getting a free music lesson just watching these guys."

Girard doesn't let it go to his head. "I'd hope that's standard fare in college towns all over the place," he shrugs.

Grafmuller thinks he's right about that, and once they're finished here, the filmmakers may go looking in Ann Arbor, San Diego, Chapel Hill, or Athens. "We hope this is the first in a series of these kinds of films where we look at the music and art cultures in college towns," says Grafmuller, who now lives in L.A. "We thought that this is the thread that would tie all those different communities together– there's always the one group of hardcore musicians who know everyone and play all the time."

Herz thinks those sorts of characters will make for compelling protagonists. "The story is about two guys who, like so many people in their teens, wanted to be rock stars so badly that they were willing to work for it and load in their own equipment," he says. "After all these years, after they've had kids and had families, they're out there again, and they're still loading in their own equipment. That's what they do.

"If we do it right, we're going to tell the story of what it's like to be an independent artist and play live, even if you're not playing Madison Square Garden," he adds.

And while Uncle Charlie's is certainly no John Paul Jones, Pastorfield and Girard had their pick of heavy-duty venues in their heyday. The Skip Castro Band followed an aggressive national touring schedule for several years in the 1980s, and Johnny Sportcoat and the Casuals played the biggest venues they could find a little closer to home. At their peak, the Casuals would regularly sell out The Wax Museum, a D.C. club– a thousand seats– without so much as breaking a sweat.

Hinton recalls one particularly lucky gig at UVA's University Hall in 1981, which landed him a managerial role of sorts with the band. When a maladroit planner inadvertently botched the airline arrangements for Bonnie Raitt's opening act, acoustic guitar virtuoso Leo Kottke found himself in Charlotte instead of Charlottesville. And Johnny Sportcoat found itself in the limelight.

"There was always either a hot local band or someone major coming through town," recalls Grafmuller. "Muddy Waters or Big Joe Turner or Bo Diddley would come through, and one of the great local bands would end up opening for them or backing them. B.B. King came to town, and all the shows that PK German put on– the Talking Heads, the Pretenders, the Grateful Dead, REM when they had just hit it big. Stevie Ray Vaughan was just unbelievable at University Hall. It was all these great international acts in addition to the greatest local scene I've ever seen."

Jimmy Carter-era UVA student Kerry Moynihan remembers those shows well. "When we went to go see the Nighthawks open for Muddy Waters, everyone knew the words," he says. "There aren't a lot of towns like that.

"The Charlottesville Blues All Stars were as good a band as you ever saw," Moynihan continues. The Reverend Billy C. Wirtz has gone on to modest success as a soloist, and Steve Riggs can still be found around these parts thumping out basslines for American Dumpster.

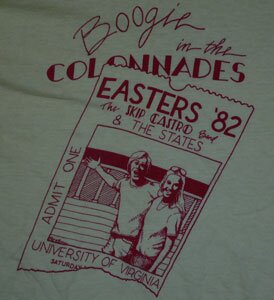

Many of those bands used to populate the stages at Easters, a sort of Foxfield-on-steroids from the more unsavory pages of the University's history book. Students would congregate in the Madison Bowl field on Rugby Road to listen to live music and drink themselves loony.

"That was a highlight for many people," recalls Bob Adamson. "The music was the focus, but people did crazy stuff just to blow off steam. It was kind of a carnival atmosphere."

Adamson was the leader (they call the position "commander") of the always music-filled Sigma Nu fraternity during his time at UVA, which wrapped in 1983. "Of course, many people don't remember those weekends because they drank too much," he notes.

James Munson was living in New York in the 1970s, but he and a car full of friends drove 500 miles from New York to visit UVA for an Easters weekend. "The police let everyone in. We were underage, and it was completely out of control," he says with a smile. "People were naked and sliding around in mud, and it was so much fun."

The upshot– if you're a square who thinks a weekend of drunken revelry doesn't qualify on its own merits– was that the bands found themselves with huge audiences thanks to road-tripping teenagers like Munson. "They could play anywhere in the state, any school, and get sellout crowds," Adamson recalls. "They were big everywhere by about 1982."

As Sigma Nu's "commander," Adamson was responsible for a lot of the audiences the bands found in their hometown because Sigma Nu fraternity was known as such a musical hotbed. After all, eventual Dave Matthews Band violinist Boyd Tinsley was one of the brothers, and he has been interviewed to share his recollections of the era.

"For such a relatively small southern town," Tinsley says in one clip, "it has always been a hip musical town."

"We were all musically inclined or passionate about the music," says Adamson. "We had a great room for it, and we also had no neighbors. Up on Rugby Road there were a lot of single-family houses that weren't students, so they had noise curfews."

Nevertheless, many of the other frats joined Sigma Nu in their musical enthusiasm and often threw parties featuring local Charlottesville bands on the weekends. Or, for that matter, on weeknights.

"We'd often throw band parties Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and then get together and throw a big country party on Sunday," recalls Hinton.

And when the University finally put a stop to the school-sanctioned insanity that was Easters in 1983, it was fraternities like Adamson's that kept the music scene going.

"The administration started to realize that partying to this degree was not necessarily a good thing," recalls Hinton. "The fraternities kept the Easters spirit alive."

But then the bands were dealt a blow from which they would not soon recover. In 1984, President Reagan signed into law a bill that deprived states of some of their federal highway funds if they didn't raise the drinking age from 18 to 21. Naturally, the desired daughter laws rippled through all 50 state legislatures.

"It was blackmail," says Girard. "You had to do it, or you wouldn't get funds to fix your roads or bridges or anything else. I think it's a fair assumption that a large part of the population who go out to see live music are under 30, and a large portion of them were 18. People became highly vigilant about it. That made a big difference, and people began to cool off on the idea of going out."

By the end of the 1980s, live venues such as the Mineshaft, the West Virginian, and the C&O Club were out of business.

"To the generation before, live music was just a way of life," adds Pastorfield. "Then all of a sudden you had kids who weren't familiar with live music and couldn't get into bars until they were 21. But by the time they were 21, they were going out looking for jobs or whatever. Some people may say that's a good thing– the kids were more productive or whatever. And that may be true. But looking at it from the musicians' perspective, it was death.

"When I was in school, the idea of a resume was completely ridiculous," he continues. "Summers weren't for being an intern, they were for partying."

Jamie Dyer, who has led the Hogwaller Ramblers for the past few decades, agrees. "It was a different generation, one not centered on alcohol, even though it was still there," he says. "It was a more literary crowd than the Charlotteville bar scene in the '70s and early '80s."

Local singer-songwriter Terri Allard contradicts outright the notion that DMB's reign over the musical scene in the early 1990s was the golden age of Charlottesville music. "The '90s were one of the driest spells in terms of full bands playing and being able to make money at it," she says. "There were one or two bands, like DMB or Jamie's band, really popping through.

"I'm not saying it was a dry spell for bands, but it was a dry spell for bands having places to play and people supporting them," Allard continues. "The people who had been supporting the Casuals and the Stoned Wheat Things and Skip Castro were getting married and having families. Clubs couldn't rely on students to support the music, and they couldn't rely on the generation before because they weren't going out every single Thursday, Friday, and Saturday."

But before blaming it all on Reagan's trickle-down alcohol legislation, remember also that the audiences for these bands were growing up. "They turned into parents," says Dyer. "They probably just got out while they could.

"But I know a lot of these folks, and it's been very cool to watch people pass music on to their kids," he says. "That's why there are so many kids coming up around here who have such links to music."

Indeed, a recent Casuals reunion out in Crozet drew both an older crowd prone to reminiscing– and their kids, the latter running around blissfully unaware of the musical heritage with which their parents were trying to stay in touch.

That's why Girard and Pastorfield aren't done yet, even though they have been stewards of Charlottesville's music for decades already. "It's becoming a generational thing," says Girard. "If they're responding as well as their parents did, in the same positive way, then we're doing all right."

They see reflections of themselves in the younger musicians around town who may become people with at least a moment of fame. "There are a bunch of young girls from [Charlottesville] high school, Counting On Jane, and they might do something," says Girard. "They may be those people, or Ravens Place, or Monticello Road. You can't tell– it's a crap shoot."

"Every college town thinks it's great for music," says Pastorfield, "but I think that Charlottesville, especially for its size, is a really fertile place for music."

Terri Allard agrees. "We have so much music in this town now," she says. "I can't believe all the venues and how much music is coming through."

Dyer, however, sees the venue explosion– and that includes the advent of the Pavilion, the Paramount, John Paul Jones Arena, and Gravity Lounge– in a different light. "Five years ago or six years ago," he says, "I at least knew the names of most of the musicians. Now I don't."

"There's another wave behind us," says Allard. "In another 20 years it'll be the Devon [Sproule]s and the Paul [Curreri]s and the Jan [Smith]s," says Allard.

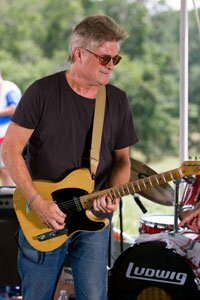

Girard and Pastorfield have not been content to rest on their laurels. These days, Pastorfield plays with Alligator and Big Circle, and following a serious injury in 2001, Girard has released a string of cathartic solo records, the first of which was titled, The Decline and Fall of John Q. Sportcoat.

Grafmuller, for one, is glad that Mr. Sportcoat didn't pull himself out of the picture entirely, since his contributions to the film have proven to be crucial. "Bob Girard and Charlie Pastorfield are kind, genuine, honest human beings, and they were open and forthcoming from the very beginning. There was no ego and pretense," he says, "They love telling their story, and this is a great way to get it out."

Pastorfield is still engaged by his musical surroundings. "From a listening standpoint, right now is the golden age," he says. "I'm scared to pick up the paper because I know that there are three or four bands that I'll just have to go to. My wife thought I was having an affair because I was going out so much."

But he's also thrilled to have a chance to help document the age of Skip Castro, their weekly shows at the Mineshaft, and the annual bacchanalia of Easter's.

"I can't think of a band that packed the house on a weekday since Dave stopped playing at Trax," Pastorfield says. "Every Monday night, we'd have 300 people, week after week, without fail, just jamming. That doesn't happen anymore."

End of an era: the second-to-last Easters.

Director of photographer Cybel Martin trains a camera on Girard and Pastorfield

Bob Girard

Not as young as they once were, fans enjoy Girard and Pastorfield's annual "Hurricane" party last month.

Charlie Pastorfield

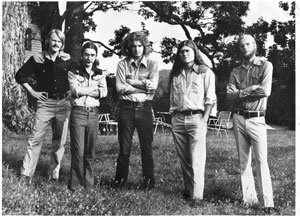

Charlottesville Blues All-Stars

courtesy of Thom Lewis

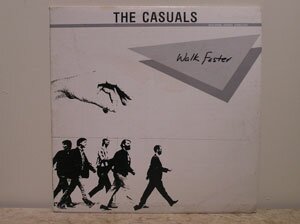

This 1982 album by the Casuals

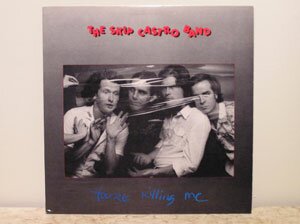

This 1982 album by Skip Castro

Two of the more popular bumper stickers of the bumper sticker era

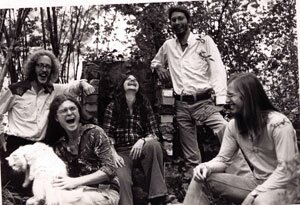

Circa 1974 photo of Capt Tunes and His Noteguns: Ralph Dammann, Bob Girard, Bill Edmonds, Charlie Pastorfield, and Gibby Dammann

Courtesy of Bob Girard

When UVA was looser, Capt. Tunes and Rock Lustre got to play Old Cabell Hall!

Last Chance Jam at Augusta Expoland

The original bumpersticker from The Casuals featuring Johnny Sportcoat

Logo by Laura Roseberry

Hammond Eggs circa 1976: Sandy Gray, Charlie Pastorfield, Judy

Coughlin, Mike Cogswell, Paul Hammond

Courtesy of Charlie Pastorfield

Live from . . . the Hook team at work at Foxfield. Director Joe Grafmuller (A&S '84) and Director of Photography Cybel Martin with Music Supervisor Chris Munson.

Live from . . . the Hook team prepares for Foxfield shoot this spring. Facing camera: producer Andy Herz (A&S '84), photography director Cybel Martin and director Joe Grafmuller. Not facing camera, Associate Producer Bill Olinger and friend wisely to remain unidentifiable.

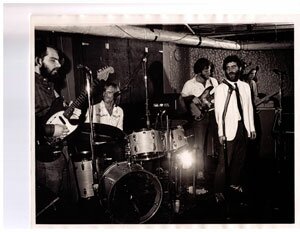

The Skip Castro Band: Bo Randall on lead, Charlie Pastorfield on bass, Danny Beirne on piano. Somewhat obscured: Rico Antonelli on drums

The Casuals featuring Johnny Sportcoat play under asbestos-covered pipe at The West Virginian, circa 1978

Courtesy Buzzsaw Films

#