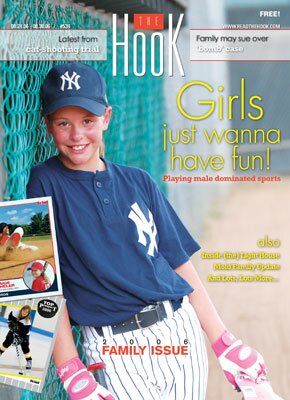

COVER-THE FAMILY ISSUE

"Kids these days." It's the phrase generations of adults have always muttered in exasperation about the young whippersnappers who frustrate them. And while the refrain remains the same, kids these days aren't your father's "kids these days."

In and out of the classroom, they're busier and more proactive than ever. Right here in Charlottesville, they're changing the face of religious education, breaking boundaries in the sports world, and even making award-winning movies.

Move over, Generation Y. Here comes Generation "Why Not?"

When in 1972 Congress passed Title IX– the law prohibiting schools that accepted federal funds from discriminating on the basis of sex– the sports world reeled. To comply with the law, high schools and colleges had to establish women's divisions of almost every sport.

By the end of the '90s, professional leagues like the WNBA and the Women's United Soccer Association had planted their flags on the sports landscape. Today, from the Independent Women's Football League to the International Female Boxers Association, it seems that for every men's sports league, women have an equivalent.

But a few aspiring female athletes in Charlottesville looked at their options and wondered, Girls' league? We don't need no stinking girls' league! All over central Virginia, from hockey rinks to ball fields, some young women feel right at home competing alongside boys.

And, in the case of at least these three contenders, they hardly "play like girls."

ANNIE LIGISH (Age 8)

Ice Hockey, Defenseman

After watching only one game, Annie Ligish knew that ice hockey was the sport for her.

"I saw my brother score a goal," she says, "and I thought I wanted to do that too."

So as soon as she saw flyers in the Charlottesville Ice Park inviting girls to sign up to play youth hockey along with the boys, she was all over it. In no time, she was also all over the ice.

And in spite of the sport's reputation as a rough and tumble game, Ligish's mother, Donna– who had already seen her two sons, John Paul (the one who scored that goal) and Joey, come up through the league– says she didn't worry about her daughter.

"They never put the kids in a position where they could get hurt," she says. "And Annie's such a tough little girl."

"It was weird being surrounded by boys," says Annie, "but I'm pretty used to it now."

In fact, Donna Ligish says her daughter is not at all shy about asserting herself during a game.

"Annie plays defense, so sometimes she throws herself on the puck," she says. "She pushes her way through the boys because she has that drive to win."

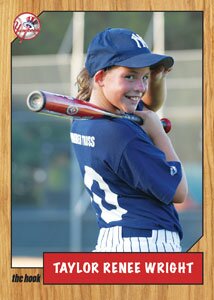

TAYLOR RENEE WRIGHT (Age 10)

Baseball, Third Base/Outfield

Like so many other players of her generation, Taylor Renee Wright's first taste of baseball didn't come from anyone taking her out to the ballgame, but from the wide world of televised sports.

"I saw a game on TV," she says, "and that's when I decided I wanted to play. It just looked really cool."

So at only six years of age, Wright got a bat and glove and signed up to play in the McIntire Little League.

Four seasons later, Wright's mother, Pat, says that coaches and teammates have treated her daughter just like one of the boys.

"Taylor didn't have games when she was taunted or teased," she says. "A couple of the guys even used her pink batting helmet and gloves."

Now that's she's had the chance to hone her skills over the course of several springs, Wright has turned into quite an adept third baseman and outfielder, though she's ambivalent about which position she likes better.

"You get a lot of balls in the infield, but I also really like catching pop flies in the air in the outfield," she says.

Her skill at both posts isn't lost on Bob Schotta, president of McIntire Little League.

"She tries as hard as anyone else out there," he says. "She holds her own."

Next month, Wright will give McIntire's all-girls softball league a try. She said she doesn't really know why she's switching, but her mother thinks she has an idea.

"They only sold pink bats for softball," she says.

PAIGE SHELER (Age 9)

Baseball, Infielder/Pitcher

Entering this year's fall ball season, Paige Sheler has one goal: reaching the major league level when Central Little League's tryouts roll around next spring.

"I'm trying to get better," she explains, "but the boys are sometimes better and so I like playing against them."

If she makes that upper echelon and plays against boys three years older than she is this coming spring, her's will have hardly been an overnight success story. Sheler was first exposed to baseball at her brother Eric's games when she was just four months old.

"Because of her brother, she's used to being around boys," says her mother, Esther. "If she had a sister, I don't think she'd feel the same way about playing with boys."

And play Sheler has, spending most of her time at second base, but also taking her turn as pitcher. Alan Archer, her coach of two years, says choosing to put "the Paigemeister" on the mound was an easy call.

"With some kids, if they make one bad throw, they can't pitch anymore," he says. "But Paige has great composure to go along with a good arm."

Her father Roger concurs. "She's played those infield positions, and because of that she definitely doesn't throw like a girl," he says.

It's a role Sheler says she's comfortable playing. "I like that the pitcher basically controls the game," she says.

Does she have any secrets for other girls looking to show off their arm?

"Just try not to hit anybody," she says.

Paige Sheler PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Annie Ligish PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Taylor Renee Wright PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Camera, action: Light House nurtures new Spielbergs

It's undeniable that today's youth live electronically saturated existences. But local kids don't have to spend hours tuned to the movie channel when they can create their own masterpieces right here in town.

At Light House Studio in the Charlottesville City Center for the Arts, workshops offer area teens a way to give voice– and images– to their unique perspectives on their lives.

"It really gave me a chance to achieve a sense of professionalism," Lucas McQueen says of the directing workshop. "It gave me confidence."

McQueen expresses a theme heard frequently at the studio. Light House alum Bremen Donovan returned from her studies at Brown University this summer to hone her filmmaking skills.

"Light House is always totally different every time I go back," Donovan says. " I always learn something completely new I would not have been able to predict."

And Light House programs don't tax teens' bank accounts. During the school year, the center offers free workshops for teenagers at the Westhaven community on Hardy Drive and at the Sunrise trailer court in Belmont.

That means kids with a wide variety of cinematic sensibilities find their way into Light House's "Adrenaline Film" program where they have just 72 hours to complete a film from first draft to final cut.

Despite– or perhaps because of– the time constraints, the exercise has produced some much-acclaimed work. Last year's Virginia Film Festival, with the theme In/Justice, featured 11 Adrenaline teams, and the team of Charlottesville High School students Evans Brown, Aaron Izakowitz and Sam Osimitz earned the impressive Jury Prize.

For the more tunefully inclined, each spring Light House collaborates with another of Charlottesville's outlets for teen expression: the Music Resource Center. Three student producers from Light House work with musicians from the MRC to create an original music video.

"It starts with a meeting," Light House managing director Cassandra Barnett explains, "where they discuss things like, what visuals do you see? what styles and feelings do you want?"

Through this program, veteran Light House student Matt Denton-Edmunson had a chance to produce a music video for his brother's band, the Wave.

"I like his music a lot," Denton-Edmunson says. "It was fun to make up a story for him and put it to his music."

"The music videos are some of the Light House students' favorites," Barnett says.

Future Walt Disneys and Matt Groenings get to breathe life into inanimate creations in Light House's summer animation workshop. After becoming acquainted with the painstaking art of animation, students create a simple story using moldable materials like clay to animate without speech, no more than a minute long.

"At first, you spend an hour and have 10 seconds of animation," says Denton-Edmunson, who made an animated short about a bank robbery. "It becomes kind of frustrating."

The students must write storyboards, create their sets from scratch, and animate them frame by frame. In the end, they combine their work into a group project.

In the Light House directing workshop, eight students working in pairs write, direct, and edit their own short films in just two weeks.

"It was one of the best experiences– not just because we made a movie," McQueen explains. "When you're working together, you can't have all your ideas take flight."

And while there may be a limited number of ideas an individual can fit into a film, there seems to be no limit on the creativity students learn to express.

Anyone interested in the Adrenaline program, but not previously affiliated with Light House can call for an application (293-6992), or download it from Light Housestudio.org. The $150 fee should not be a deterrent since scholarships are available. Oh, and there is one other, minor, inconvenience.

"You have to miss a day or two of school," says Barnett. "Some kids really like that."

Light House alum Bremen Donovan decided to use her summer off from Brown University to return to the studio as an intern. PHOTO BY DANIELLE UNGER

Lucas McQueen PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Matt Denton-Edmunson PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Making menschen: Jewish school preps for 2nd year

<>When the Charlottesville Community Jewish Day School opened its doors last fall, welcoming six students in kindergarten and first grade, parents and administrators knew they would face a challenge in attracting new students and funding in the future.

Unlike the Charlottesville Day School– which will open at ACAC this fall with 100 students in three grades– the Jewish Day School didn't have the backing of a huge corporate entity and instead relied entirely on donations, tuition, and grants. But despite a bumpy first year that included the original head-of-school leaving mid-year and the unexpected need for a new location, current head of school Jan Chase says year two is shaping up for success.

"All of our students are returning," says Chase, who adds that she believes the quality of instruction and the school's emphasis on academics and Jewish culture not only has kept current families satisfied but will attract more students in the future. This year, two new students are joining the community, she says, bringing enrollment to eight.

Chase, whose background is in fundraising and who previously worked at a Jewish school in Washington, was hired mid-year, when the school's first director, Dick Lavine, left the position for health reasons, Chase says.

The second blow the school faced: learning that it would need to vacate its downtown space on the second floor of Christ Church after one year instead of the originally planned two.

"They decided to renovate," explains Chase, who says that despite the change, the church– which had offered the school space rent-free– has remained "incredibly supportive," donating furniture and assisting in the school's move to its new location at the east end of the Downtown Mall next to the transit center.

That move, Chase says, has worked out well, providing nearly twice the area of the old space as well as a full kitchen. Students use the kitchen for such cooking projects as baking their own challah– traditional Jewish bread– on Friday in preparation for Shabbat (the Jewish sabbath that lasts from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday).

Other good news: for the second year in a row, Chase says, the school has received a $60,000 matching grant from the Partnership for Excellence in Jewish Education, something she says is helping to offset this year's unexpected $20,000 rent bill.

"I've been really happy with Charlie's progress in reading, and his general interest in learning," says Drew Alexander, whose son will enter second grade this year. Praising the school for its "tight-knit" community, Alexander believes the new space and new leadership are both good things, though he admits they may have made recruitment of new students difficult.

"We're in a good place," he says. "We're in a better space now than before; we have more room, and it's air conditioned."

This second year, however, is a "very critical year," admits Chase, who says she's working to get the school's name out and to let people know "what it means to be a community day school."

While students participate in a curriculum that includes everything from social studies to yoga to Hebrew taught by a native speaker, a family's religious practice isn't important.

"We don't care what people are," Chase says, adding that current students come from the full spectrum of Judaism– from Hasidic to secular– as well as one student who isn't Jewish.

"We're trying to raise menschen," she says, using the Yiddish word for "admirable human beings."

Corrections have been made to the online version of this story.

Charlie Alexander and Reuvi Mayer get ready for their second year at the Charlottesville Community Jewish Day School. PHOTO BY COURTENEY STUART

Charlottesville Community Jewish Day School director Jan Chase with students Reuvi (front) and Meni Mayer. PHOTO BY COURTENEY STUART

Still moldy: Family's American dream goes sour

Two days after Larry Butler and Judit Szaloki bought their first home in February 2005, their asthmatic daughter ended up in the emergency room, and the married couple discovered the Wayne Avenue residence was infested with mold.

After it was suspected that moisture problems had been covered up and their story was reported in the Hook, the community rallied to help the financially devastated family. ServiceMaster provided free mold remediation that might have cost $30,000. Contractor Bob Fenwick stopped the water coming into the house, and for months, he came by after work and on weekends to get the place back in shape. Volunteers made donations of materials and labor.

A year later, the house for which the Butlers paid $246,000 is barely habitable. Their cars have been repossessed, and they use food stamps to put meals on the table. Facing bankruptcy, they wonder where their family of six will live when the inevitable foreclosure occurs.

"Everyone assumes we're doing much better and the house is back together," says Szaloki. Instead, the family camps out in the house, eating on the floor and sleeping on mattresses because, they say, the furniture they moved in became contaminated and to be discarded.

Only one of three bathrooms has a working toilet, sink, and bath. The kitchen has no appliances, sink, or cabinets. Szaloki uses a downstairs kitchen, cooking on a stove with one working burner. The sink backs up, and plumbers have told her it's a drainage problem that will cost tens of thousands to fix.

She'd planned to move the daycare business she'd run for 20 years into the basement of the house, but when word about the mold infestation spread, she lost her clients. And even though the house has been cleaned, with no working bathroom downstairs and a sketchy kitchen, Szaloki hasn't been able to reopen the business, which she and Butler had counted on to pay the mortgage.

Butler still has his Ivy Square business, Uncle Larry's Toy Shop, which brings in enough to cover its expenses, but little more. "I'm not going to close the store and get a regular job," insists Butler. "I've got a regular job." The former Marine now moonlights as a bouncer.

They've been paying about $400 a month on their $1,700 mortgage, and he figures they're behind about $22,000. "Our mortgage company sold the loan," he reports, "and they told us we have to come up with $4,000 by the end of the month."

That might explain some recent visitors– the contractor who said he was instructed to change the locks, the woman who hid in the bushes and took pictures of the house.

Daughter Emese, a senior at Charlottesville High, has a job at Red Lobster, within walking distance of the house. She was saving for a trip to England next year with the school orchestra. Instead, says her mother, Emese's earnings are going to pay the phone bill, or to reconnect the water service after it was cut off, or for food when the $600 in food stamps runs out.

"It's affected me in more ways than one," says the teen, who finds herself more prone to illness since moving to the house. "I'm mad. I'm upset."

Most of all, she doesn't understand how her parents could have been sold a house with such major problems. "I really want to blame everyone who put us here– Real Estate III, Montague Miller... They knew it had flooding," she says.

The experts who came in to clean up the house were extremely dubious that former owner Steve Dudley didn't know about the flooding in the house. The mold-infested basement had been freshly painted when the house was listed for sale.

And the Butlers allege their real estate agent, Sirlei Kaiser-Ramirez, misled them when she told them the mold, which was noted in a pre-sale home inspection, could be wiped down with Clorox.

Dudley and Real Estate III spokeswoman Pat Jensen had not returned phone calls by press time. Listing agent Shann Whited declined to comment.

"I know there are people who have worse problems," says Emese, "but I can't be cheery and smiley."

"This is an unusual situation," says the mold remediator Fenwick. "It doesn't happen often. I was disappointed with the real estate agency. They could have turned this around. And with the inspector for not making it known how bad the mold and mildew were."

Fenwick estimates it would take up to $60,000 to get the house into shape– and that doesn't include the money owed to the mortgage company.

"Bad things happen to good people," he says. "The community helped out, but this was so out of whack."

The situation has affected the entire family. Szaloki and Butler report depression and strains on their marriage. "Larry, after 10 years in the Marines– this is a man used to being in protective mode," says Szaloki. "This is so unfair."

And Szaloki's dreams of creating an "amazing" daycare are dashed. "I have a talent for children," she says. "I have raised half of Charlottesville. Now I can't take care of them. I don't have a place."

The Butlers have met with bankruptcy lawyers and seem resigned to the notion that a Chapter 7 is in their future. Even with that option, "We can't afford it," laments Szaloki. "They all want money upfront"– at least $1,200.

And they shudder at the cost of rent. A two-bedroom apartment near Butler's store costs nearly $1,400, "and there are six of us," he points out.

After 18 months in a nightmare from which she can't wake up, Szaloki despairs. "I don't want to keep going underwater. I just want a bed. I just want a bathroom."

She has one other wish. "I'm sorry I'm not a gutsy lawyer who could take this on."

High school senior Emese Szaloki, in one of the Wayne Avenue house's non-working bathrooms, contemplates her family's future.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

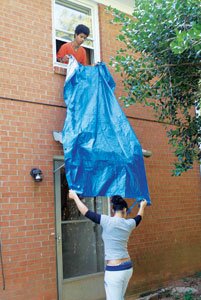

Eric and Emese Szaloki spread a tarp to keep water from coming in under the door.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#