NEWS- At Peace (Corps): Scam victim finds joy in Africa

If life hands you lemons, you can always make lemonade. But if one of the lemons bilks you out of your money and leaves your life in shambles? Well, if you're Margaret Jackson, you join the Peace Corps and put the past behind you.

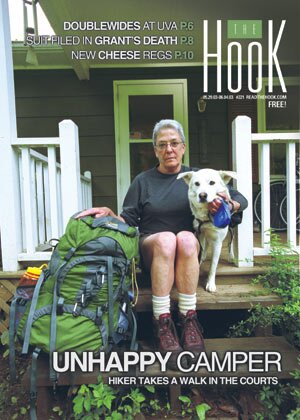

Remember the woman described on the cover of the Hook three years ago as an "unhappy camper"? Well, that was then.

"I am the happiest I have ever been professionally," says Jackson, temporarily back in Charlottesville after a two-year teaching stint in an African village. But her home stand will soon end, as she signed on for a third year with the Corps and will joyfully return to Ghana in early September.

"I feel such a sense of purpose when I'm there," says Jackson, 59, who survives in Ghana on her $150-per-month Peace Corps allowance. That sum, while paltry by U.S. standards, is many times the income of the average family in Mepe (MEH-PAY), the village in the Volta region of Ghana where she is the sole westerner. Yet despite her limited resources, "I have everything I need," she says.

Jackson was considerably less happy during preparation of the Hook's May 29, 2003 cover story, "Unhappy camper: Hiker takes a walk in the courts." It detailed Jackson's damaging run-in with Will Morrell, a man who promised to help her, but took her money instead.

A lifelong smoker, Jackson had so completely converted her cigarette habit into an exercise habit that she became a spokesperson for Atlantic Coast Athletic Club. Morrell was an unfortunate ACAC connection.

A physical trainer who encouraged Jackson to pursue her dream of hiking the Appalachian Trail and writing a book about it, Morrell turned into something of a textbook study of broken promises.

After he promised Jackson a $150,000 loan, she quit her job as a graphic designer, spent her savings on camping equipment and trail gear, and planned to start her six-month hike in March 2003. But the money Morrell promised never materialized, and Jackson soon realized she'd been bilked out a supposed loan fee.

Though a $750 judgment was entered against Morrell, he made just one payment of $100, promising the rest would soon follow. It never did. In fact, mistreating Jackson was the least of his transgressions.

When Morrell's multiple scams caught up with him in April 2004, he was sentenced to five years in a federal penitentiary for swindling more than 20 victims via the U.S. mail.

Morrell remains behind bars in Petersburg and did not respond to the Hook's request for an interview. He's scheduled for release in April 2008, according to the federal prison website, bov.org.

Although Morrell was sentenced to 60 months, Asheville, North Carolina-based US attorney Richard Edwards, who prosecuted the case, says federal prisoners who receive more than a one-year sentence can get up to 15 percent of their time reduced for good behavior. Once released, Morrell must begin making restitution of more than $1.5 million to those 20 victims (not including Jackson, who was not part of that federal case).

While Morrell languishes behind bars, Jackson says she is looking forward to another year teaching visual arts– textiles, graphic design, and art appreciation– to students, many of whose families survive on less than one dollar a day.

Jackson says she has adapted to life in a third-world country. Most meals consist of simple food like rice and tomato stew. She bikes half a mile through the bush from her small bungalow to her "classroom," essentially a thatched roof supported by four poles and equipped with only a chalkboard and a couple of tables.

But despite their material deprivation, most of her students speak English in addition to their native language, Ewe (AY-WAY), she says, and several show signs of giftedness. While she's in Charlottesville, she's trying to raise funds to help three of her students attend a private college two and a half hours west of the village.

"It would give them and their families such an advantage," she says, pointing out that a neighboring village's "chief" is a banker who was educated in Britain and returned to assume a leadership position.

The Ghanaian people, she says, are "kind, generous, and proud." But poverty is a way of life, and girls, in particular, are often taken out of school when their families can no longer afford tuition of approximately $60 a year. In fact, Jackson has taken under her wing a 16-year-old girl who was abandoned by her family, and she hopes to help the girl return with her to the U.S. next year.

Jackson is spending much of her time at home looking for ways to assist the villagers, who in many ways she now thinks of as family. She brought fabrics dyed by her students to Charlottesville and sold her first batch to local crafts business Innisfree. All the proceeds, she says, will go back to the village.

"I have been blown away by how generous people in Charlottesville have been," she says.

Despite the harm Morrell inflicted on her, Jackson says her life is going better than she ever would have imagined. And she wonders whether she'd ever have had this experience if it weren't for Morrell and his scheming ways.

"I'm not saying I'm grateful to him for stealing from me," she says, "but everything happens for a reason."

COVER PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Margaret Jackson was named an "honorary queen mother" during the Hogbeza Festival in a town near her village. PHOTO COURTESY MARGARET JACKSON

Jackson hopes to help raise money to cover the cost of surgery for Evans Morkli's knee, damaged by childhood malnutrition. PHOTO COURTESY MARGARET JACKSON

#