COVER- My 'Pet Virus': Decker finds humor in his life with HIV

When Shawn Decker started circulating his memoir to agents, he figured he'd get the response most first-time authors get: silence– or at best, a few "No, thanks." Instead, Decker beat the odds.

Not only did 10 of the 20 agents he contacted respond favorably, but he went on to land a contract and a five-figure advance with a top publisher. His book, My Pet Virus: The True Story of a Rebel Without a Cure, hits bookstore shelves next week, and Decker hits the road for a nine-city book tour.

But while the book deal with Tarcher/Penguin may be sweet, for Decker, beating other odds has been even sweeter. Diagnosed as a baby with hemophilia– and with subsequent diagnoses of Hepatitis B, C, HIV, and finally full-blown AIDS– Decker shouldn't even be alive, statistically speaking. Never mind writing a book, let alone one that Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil author John Berendt calls "enlightening, compassionate, hilarious."

Hilarious? A book recalling a childhood spent in and out of the hospital, getting kicked out of school for his illness, and ostracized even by his own godparents?

There was no shortage of material, says Decker as he describes the book's beginning: "Like any good movie, it starts with a bloody episode." He's referring to his circumcision as an infant– the moment doctors realized he had hemophilia. Later chapters cover youthful "shenanigans" in his rural hometowns of Buena Vista and Waynesboro.

In the book's first pages, Decker, now 30, eschews usual medical terminology– hemophiliacs are renamed "thinbloods," HIV-positive individuals become "positoids" (and their opposites "thickbloods" and "negatoids"). "I should be able to introduce myself and my gaggle of viruses and diseases without needing a hit of oxygen," Decker writes.

And although his illnesses are a part of the story, Decker says they're not the stars of the show.

"My medical conditions are floating there in the background," he says. "It's kind of how my life has been shaped by them."

Early reviews suggest Decker made the right decision to tackle weighty subject matter with levity. Heather McCormack in the Library Journal lauds the Gen Xer for skipping self-pity and self-loathing, "a bold move in our misery-loves-company culture."

Indeed, there are episodes in the book that detail Decker's many hospital stays– gushing nosebleeds stanched only by trips to the ER, and episodes of frightening weight-loss and near death. But they are balanced by the Tom Sawyer/Huck Finn adventures Decker has with his two best friends, Michael and Jared, and his older brother, Kip, whom Decker portrays lovingly as equal parts tormenter and protector. Kip may deliver devastating body slams, but when the younger boys discover an X-rated treasure, Kip is there to help retrieve it– and to take the fall, without complaint, when the group is caught.

While Decker's father, Buddy, makes regular appearances through the book, it's Decker's mother, Pam, whom Decker portrays as a force of nature, refusing to allow her younger son to be victimized or to be intimidated by doctors, school administrators, or ignorant neighbors.

Considering attitudes toward AIDS in the early to mid-1980s, when the disease was little understood and almost universally seen as a death sentence, Decker's mother had a formidable task in helping her family navigate frequent, frustrating obstacles.

Decker writes that in 1987, just after he had tested positive for HIV, he was told he could no longer attend Westwood Hills Elementary School by order of the Waynesboro school board. His two best friends were no longer allowed to play with him, and even his godparents cut ties with him. And he was not the only child in America facing such a fate. Ryan White, also a hemophiliac who contracted HIV from a tainted transfusion, was making headlines at the time for his expulsion from an Indiana school.

Despite Decker and his mother's recollections, then-superintendant of Waynesboro Schools, Thomas Varner, denies Decker was ever prevented from attending school and says Waynesboro was among the first schools to implement an official policy regarding HIV-positive students.

"I think he would like to appear to be some type of pioneer, and he may be– in his mind only," says Varner, insisting, "There was no individual who fought for HIV rights in Waynesboro schools."

Pam Decker scoffs– with a few harsh adjectives– at Varner's memory, and says she helped pen the policy Varner mentions after being told her son wasn't welcome. Another Waynesboro school administrator, Maggie Van Huss, now director of student services for Waynesboro schools, says Pam Decker was an integral part of crafting the school's HIV policy during the summer after Decker's sixth grade year, but says she has no memory of Decker being prevented from attending school. "I won't say it didn't happen," she says, "but I don't recall that piece of it all."

Decker himself is gentler than his mother in his response to Varner's claim.

"I've never had the opportunity to speak to Tom in person, but I'd love to have a discussion about everything that happened, maybe over a beer," he says wryly. "And if that doesn't work, I guess we'll have to settle it the old fashioned way– with mud wrestling."

From the time Decker left school in May 1987 until that July, his mother says she petitioned the Waynesboro school system until it finally allowed him to re-enroll the next year for seventh grade.

But while she was publicly fighting for her son's rights, Decker himself was not thrilled to be the object of such attention. When his mother asked him if he'd like to go public, like White, to help raise HIV awareness, Decker declined. An adoring fan of professional wrestling, and Ric Flair in particular, Decker imagined a WWF-like confrontation with White.

"I wasn't the kind of kid," he writes, "who wanted to waste my breath on a bunch of morons who thought that HIV could be transmitted through handshakes or wedgies."

Though his mother may have wished Decker would speak out like White, she didn't agree with everything the Whites did, especially the treatment Ryan White received, the early AIDS drug AZT. Pam Decker defied doctors' recommendations that Shawn take AZT, believing the drug's harsh side effects were not a good match for hemophiliacs. White succumbed to AIDS in 1990 at age 18.

For Decker, however, surviving came with its own complications. As he details in his book, he was close to 20 when he realized he might actually live to see 40, a realization that prompted a midlife crisis of sorts. Decker, who hadn't applied for college and had dreamed only of rock stardom, suddenly realized he needed a purpose and a way to fill his days. The purpose, he decided, was already inside him– and multiplying.

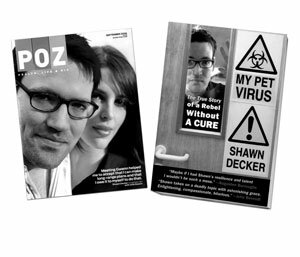

In 1996, Decker launched a website, mypetvirus.com, to educate people about HIV and AIDS. The site, which he still maintains, quickly brought him some national attention. That same year, he became the cover boy for a new national magazine, Poz, and later wrote a monthly column. In 1997, he met then-vice president Al Gore at World AIDS Day. By 1998, he was featured on an MTV special.

And then along came Gwenn.

While living in Charlottesville at that time, Decker met Gwenn Barringer through the AIDS Services Group, where he volunteered. Barringer, a leading Miss Virginia contestant, was an AIDS activist who'd interviewed Decker a short time earlier for a graduate school project.

"I was a little smitten," Decker admits.

The feelings were mutual, and for the past eight years, Decker and Barringer, now married, have traveled the country, speaking at schools and answering questions. ("Yes, we can have sex." "Yes, we can have children." "No, we don't think about death constantly.")

Decker says Barringer, who works as manager of Goth band Bella Morte, pushed him to write the book and encouraged him to "write your truth" rather than mimicking the educational tone of a speech.

For Decker, that included writing about past relationships. "Falling in love, each time you do, alters who you are," he writes, "and so I didn't want the book to be all about how HIV has affected me. People affect you more than medical conditions do. That cuts both ways, positive and negative."

Barringer says seeing Decker through the book process has been "really cool," and as for Decker getting more time in the publishing limelight, Barringer's okay with that, too.

"I've always been the better speaker," she says, "and he's always been the better writer."

She's not the only one who admires Decker's writing style.

"His comic timing is perfect," says Decker's New York agent, Christopher Schelling, who also represents acclaimed memoirists Augusten Burroughs (Running with Scissors, Dry) and Haven Kimmels (A Girl Named Zippy). "He really knows when to give you the emotional and then reel you in with the perfect punchline," Schelling says.

Tarcher/Penguin editor Ken Siman says it was Decker's "original comic voice" that earned him the deal. "You can fake a lot of things in life, but you can't fake laughter," says Siman, who also works with Erica Jong and Larry Cramer.

That comic voice, Siman adds, allows Decker to address subject matter "that could be tough to some people." Decker is living proof, Siman says, that "if you tell a story well, you can tell any story and get people behind it."

Though writing a memoir can involve a few sticky wickets– telling stories some family members may not wish aired or fabricating history, a la the infamous recent case of James Frey– Decker seems to have avoided them, as Barringer and his family praise his accuracy. Mostly.

"I think he made me sound better than I deserve to be," laughs brother Kip, now a chemist working for Merck in Elkton. "I thought there'd be something there that would cause me to say, 'You're full of it,'" he says, "but there isn't anything that I could say didn't happen."

For Pam Decker, reading her son's memoir provided a way to see his childhood from a new perspective: his.

"You're so busy trying to keep them alive, you wonder how they're feeling and what they're thinking," she says. After she and husband Buddy read the book, "We felt like we'd done a pretty decent job," she says, "'cause he seems pretty happy."

The book did hold a few surprises for mom.

"They viewed us as hip sex fiends?" she laughs. "Wow! I was directing the church choir."

That his parents laugh easily and roll with the punches is a gift Decker says has helped him not just survive, but thrive. Local audiences can find out for themselves on the book's launch date, September 19, when he speaks at Barnes & Noble. UVA hosts him a day later as he embarks on his national book tour.

"I was taught at an early age not to feel sorry for myself," he says, "that life is to be enjoyed, and that there are some twisted things about the human experience, but that's what makes it fun."

Apparently that lesson translates to print as well.

Shawn Decker and Gwenn Barringer

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Pac-Man fiend Shawn Decker, age 7

PHOTO COURTESY SHAWN DECKER

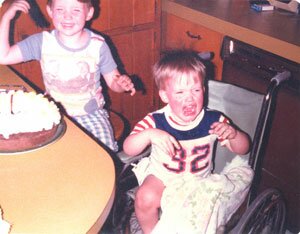

Decker, front, at 2 with big brother Kip

PHOTO COURTESY SHAWN DECKER

The Deckers: (from left) Buddy, Kip, Shawn, and Pam. "You're so busy trying to keep them alive," says Pam," you wonder how they're feeling." After she and Buddy read their son's book, she says, "We felt like we'd done a pretty decent job."

PHOTO COURTESY SHAWN DECKER

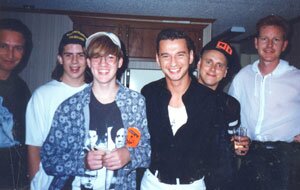

A teenaged Decker meets his rock idols, Depeche Mode, courtesy of the Make-A-Wish Foundation.

PHOTO COURTESY SHAWN DECKER

Decker appeared on the cover of Poz magazine for the third time in September; Decker's book hits shelves September 19.

#