COVER- JPJ rocks: But what about ol' UHall?

Jim Connelly remembers everything about the first game played in University Hall. It was a December 4, 1965 contest against Kentucky that the Wildcats, on their way to the NCAA title and immortality in the Disney film Glory Road, won by 99-73. Connelly, a 6-3 guard, was overshadowed only by Kentucky forward Pat Riley, later the coach of the Los Angeles Lakers, New York Knicks, and this year's NBA champion Miami Heat. He remembers everything– "the game situations, who I guarded, who guarded me, all of those kinds of details." He also remembers what University Hall meant to UVA's basketball program.

"Building University Hall was obviously a significant step up," Connelly says.

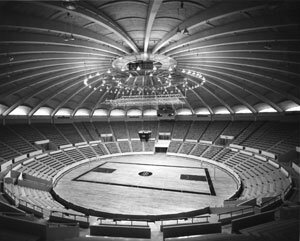

In fact, UHall was a giant leap. With a seating capacity that could swing from 8,300 to as many as 12,000 fans, UHall dwarfed the 2,000-seat Memorial gymnasium built in 1924 for a much smaller University of Virginia.

"Mem Gym was built for a student population of 1,500 to 2,000," explains UVA architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson. "The University's population was in the area of 5,000 students in 1959. But within 10 years, it had increased by another 5,000 students. University Hall was a response to this growth, in addition to being a response to our entry into the ACC."

Inspired by Nervi

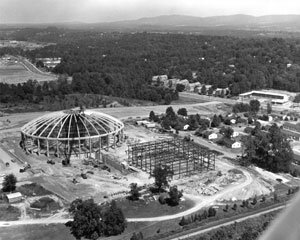

Virginia had joined the Atlantic Coast Conference in 1953– and keeping up with Duke, North Carolina, and NC State wasn't going to be easy. Work on the $4 million project began in 1960 with the selection of Lawrence Anderson, dean of the architecture school at MIT.

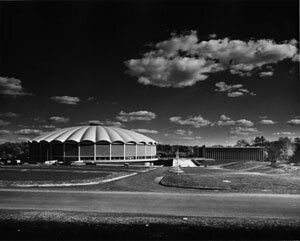

"He was drawing from the major central building for the Summer Olympics in Rome in 1960," says Wilson. "A well-known Italian architect, Pier Luigi Nervi, had experimented with reinforced concrete-cable sorts of structures– which are basically circular in form. From that point of view, it's very significant– because you might say it was the first modern building at the University."

Modern architecture-lover Christine Madrid French is aware that some people ridicule UHall's unusual appearance– some have even referred to it as a "pregnant clam."

"You say, 'Why would you put that there? It's so out of place,'" she says. "But when the buildings were constructed, they were intended to really make a statement."

French, who leads a group called the Recent Past Preservation Network, says UHall "set the tone" for coliseum building in Virginia, which would soon get a host of new ultra-modern arenas including the Hampton Coliseum in 1970 and Norfolk's Scope the following year.

"UVA wanted to show it was a leader," says French. "It was building what was basically the largest indoor stadium in the state at that time– and it wanted a bold statement."

The statement included borrowing the primary shape of probably the most obvious building at the University: Jefferson's Rotunda.

"If you really look at the building, you'll see that it has a lot of relationship to more typical UVA architecture," says French. "It has the brick– the brick with the white combination.

"Jefferson, though, who was a great fan of the neoclassical," French says, "was also always trying to insert innovative concepts into his architecture. So you could say also that this stadium is innovative– which I think Jefferson would have approved."

The primary motive might have been building a big-time basketball program, but like the now-rocking John Paul Jones Arena, the building had other purposes.

"A major part of the focus was not about sports– it was about performances," says Mark Fletcher, an associate athletic director at UVA. "In the aisles you can see the lights on the steps. When they had a production in here, they could turn on the lights just like in a movie theater."

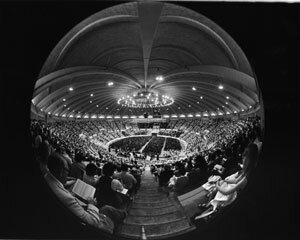

But while University Hall has hosted theater productions, music concerts, and even a White House education summit, the building has critics who have berated its poor acoustics and distant sight lines.

Bob Moje, a UVA graduate who led the planning and design of John Paul Jones, says he thinks University Hall has been unfairly maligned.

"University Hall was not a bad building," says Moje. "One good thing about a round building is that it focuses all the sound into the center. So it does create sort of an acoustic home-court advantage for basketball purposes."

But what's good for scaring visiting teams may not help visiting artists.

"The building came out of a very simple idea– trying to use an innovative, repetitive casting of concrete as an economical way to make a big space," Moje says. "It was sort of a victim of its time in history."

UVA basketball was also a victim of sorts back then. The Cavaliers, who began ACC conference play in the 1954 season, finished no better than fifth in their first dozen years in the conference and compiled a miserable 15-69 record between the 1959-1960 and 1964-1965 campaigns. It wouldn't get better until year six of the UHall-era.

On January 11, 1971, a jump shot by a 6'4" sophomore guard named Barry Parkhill swished through the net in the final seconds to give the Cavs a 51-50 homecourt victory against second-ranked South Carolina.

"The South Carolina game was huge," says Parkhill, now an associate athletic director at UVA who helped raise much of the funding for UHall's replacement. "But that week, in a period of eight days, we beat Clemson at home on Saturday, we beat South Carolina at home on Monday, we beat Wake Forest at home on Wednesday, and we beat Georgia Tech at home the following Saturday. Those were four huge wins, and after that stretch we were ranked in the top 20 for the first time ever."

Many in Virginia basketball circles saw the Parkhill jump shot as a turning point.

"We went from the situation where the first home games I saw in University Hall as a freshman were very poorly attended," says 1973 Virginia grad and basketball alumnus Jim Hobgood. "Two years later, students were camping out to get tickets."

In the fall of 1979, University Hall became the center of the college-basketball universe when a lanky teen named Ralph arrived from Harrisonburg.

"It was the high point of men's basketball at Virginia," says Moje, a long-time season-ticket holder. "You went into every game with the expectation that they would win."

Ralph Sampson's teams went 49-2 at home in his four years in Charlottesville– the losses coming in his freshman year, 63-61, and in his senior season, 101-95, both to North Carolina. For radio broadcaster Mac McDonald– whose first season covering UVA basketball was the 1980-1981 campaign that saw Virginia in the Final Four for the first time in school history– it was like living with the Fab Four.

"I was blessed to come in with a team that was bigger, really, than The Beatles at that time," McDonald says. "Ralph Sampson was a sophomore. We had Jeff Lamp, Lee Raker, Jeff Jones, Terry Gates, all these guys. I remember the crowds, and how big every game was. We played Randolph-Macon that first year! It didn't matter who it was– because Ralph Sampson was there."

What Jeff Lamp, an All-American guard on that 1980-1981 team, remembers most about the Sampson years is how it was "always impossible" to get seats. "People were waiting outside for tickets," he says. "It got really rabid, especially when Ralph got there, and in my senior year once we started that 23-game winning streak. I don't know if they added seats, but it sure seemed like it. One of the great things about it was everybody was just right there on the court– almost right on top of you," says Lamp, who went on to six seasons in the NBA.

"We had a lot of great players– Jeff Lamp, Lee Raker, Othell Wilson, Jeff Jones," says Ricky Stokes, a freshman on the '80-1981 team and now East Carolina's head coach. "It was a good group of guys who played well and, I think, really identified with the community and the University, and vice versa. It was a special time."

The hot-dog disaster

An experience that proved unrewarding was one of the early highlights of Virginia women's basketball. After some early struggles, the program got on track under coach Debbie Ryan– and the lady Cavaliers, ranked third in the nation, were entering a February 5, 1986 home game with North Carolina.

Kim Record, then the director of athletic promotions, had an idea that will forever be known as Hot Dog Night. The goal: to break the ACC attendance record. The plan: free admission including hot dogs and soft drinks.

The buzz Record had hoped to generate for the women's program quickly spread. Ryan began making public appearances, and Record pushed a halftime skirmish between members of the media, figuring it was a good way to get them to write about the game.

Now a senior associate athletic director at Florida State, Record recalls walking into the office of Todd Turner– then her boss and now the athletic director at the University of Washington– to ask him if the athletic department was prepared if it happened that a flood of fans turned out.

"None of us really knew," Record says.

What they did know was that by the morning of the game, a good eight or nine hours before tipoff, fans were lining up outside University Hall. From what Record remembers, the line stretched had all the way to Emmet Street by noon.

By the start of the game, it was hard to tell exactly how many people had showed up. The announced attendance was 11,174, but Record thinks it topped 13,000. Either way, the number was well over the official capacity of 9,000 to 10,000.

Unfortunately for UVA, one of those on hand for Hot Dog Night was the local fire marshal. After he finished his report, UHall's capacity was reduced, eventually to 8,392.

"So the promotion was a huge success in that we set a women's record at that time for attendance," says Terry Holland, the head men's coach from 1974 to 1990. "But it cost us about 1,800 seats for future years– at least 300 games since then. At an average of $20 per person per game, that comes to well over $10 million in lost revenue over the last 20 years for UVA. What a great promotion."

Another event three years later brought more attention to UHall and the University.

"The year was 1989, and President George H. W. Bush convened a National Education Summit," remembers political-science professor Larry Sabato, who was at the center of the cerebral action. The summit brought together "Bush 41" and the governors of the 50 states to talk public education in Charlottesville and UHall.

Sabato recalls the walk down The Lawn led by President and Mrs. Bush and Gov. and Mrs. Clinton who were representing Arkansas and the National Governors Association, of which Clinton was then serving as chairman. "At that time, no one had a clue– including the Bushes and Clintons– that three years later these would be the principals in a life-or-death struggle for the presidency," Sabato says.

A 'dark, dingy' place

Long before the education summit, University officials were already expressing frustration with the indoor arena. Former assistant coach and now UVA athletic director Craig Littlepage says the Sampson era boosted ticket demand tremendously. "We were talking at that time about the need to replace University Hall," Littlepage says, "because it was just not big enough to suit the demand."

Many thought that the building, then less than two decades old, could be expanded, but a feasibility study suggested that adding 1,000 more seats would cost around $40 million. "That just didn't seem to be cost-efficient," Littlepage says, "so that whole plan was put on the back burner."

Enter Moje, a principal in Charlottesville-based VMDO Architects. He got the call when the athletic department decided it had to do something to spruce up University Hall after Virginia Beach basketball star J.R. Reid (who eventually played in the NBA) chose to become– not a Wahoo– but a Tarheel.

"J.R. Reid had come to UVA on his recruiting visit, and was famously unimpressed with UHall," Moje says. "He called it a 'dark, dingy place'– and that was one of the reasons he went to North Carolina. So somebody stepped forward and said, 'Okay, we need to make some improvements. What can we do relatively quickly?' One thing was to redo the locker room."

The locker rooms gleamed, but they did nothing to change the post-Hot Dog Night capacity, but to quote early-1990s coach Jeff Jones, UHall "wasn't necessarily the Taj Mahal of college basketball."

Terry Holland returned to the University in 1995 to take over the athletic department with a bold vision.

"He didn't think it was smart to spend the money to renovate UHall when we should really be looking at a new facility," says Dirk Katstra, executive director of the Virginia Athletics Foundation.

Holland, now the AD at East Carolina, says his effort to replace UHall was "one of the hardest battles I had to fight. Luckily, President Casteen agreed with me."

In August 1998, a UVA worker spotted corrosion in the stranded cables that encircle the structure. Employees were immediately evacuated, and a two-month, $2 million repair job was ordered to make the place safe for the basketball season.

Three years later, Paul Tudor Jones, UVA '76, decided to jumpstart a replacement. "It's long overdue," he said at the time of his 2001 announcement of his $20 million gift for a new arena to be named for his father.

Five years and $130 million later, the John Paul Jones Arena opened this August 1 with a performance by Cirque du Soleil. Concerts followed by James Taylor, Kenny Chesney, and– just this past weekend– a tour-ending double shot of the Dave Matthews Band.

The Mitsubishi Diamond Vision screens are part of the $7.5 million audio-visual system, and the first basketball games are scheduled for November 12, around the time it will begin to sink in for some former players that it's time for UHall to fade into the sunset.

"They had the ceremony at the end of the year," says Hobgood, "but it may not be until I do the first game next year and realize I'm not going to University Hall; I'm going across the street to the new place."

Wither the clam?

What will happen to University Hall from here is anybody's guess.

"Clearly, a lot of other buildings like this are still standing," says the athletic department's Fletcher, "like Carmichael at North Carolina. NC State still has Reynolds; Cole Field House is still at Maryland."

Fletcher says UVA wants to see if there's demand for UHall now that its flashier, air-conditioned replacement has opened. Until schedule conflicts with UVA women's games, Virginia's high school basketball championships were held at UHall.

"This opens it up to come back here again," he says.

So the sounds of basketballs bouncing and fans cheering might again echo in UHall– for a few years, anyway. The long-term plan is to tear the building down– though Parkhill emphasizes that's "way down the road."

"When you stop and think about it," he says, "it's going to cost a whole lot of money to make UHall disappear. We're talking about a period of five to 10 years before we can get that going."

Parkhill won't cite a dollar figure for the demolition project– in part because UVA officials want to replace University Hall with a fieldhouse, he says. "It's all talk right now. But when I say fieldhouse, I mean an indoor practice facility for football, lacrosse, soccer, track.

"It's something we need, and we don't have anything close to it," he adds. "We know what we want to do, but it's several years down the road."

That will be a sad day for Ryan, whose affiliation with Virginia athletics and University Hall dates back 30 years. Speaking after the last regular-season home game for her team in UHall, an 83-64 win over Clemson on February 26, Ryan was caught up in the moment.

"I had no idea about the confetti or the balloons or any of that," says Ryan, who took a ceremonial last shot. "So when that all started, I was like, 'This is big-time. This is like Hollywood– like a movie.' I thought it was just a great sendoff for her."

Men's basketball coach Dave Leitao had mixed emotions after his team's last game in University Hall– a 71-70 loss that came down to the final seconds. In what was a cruel twist of fate, just moments after the last-second shot by guard J.R. Reynolds had fallen harmlessly out of the lane, somebody handed Leitao a microphone– to begin the postgame ceremony.

"You can understand, for obvious reasons, how difficult this is for me," he said. "We fought, we scrapped, and we clawed– and obviously came up a little bit short today. But I wanted to win for you and our players more than anything that I've wanted in my life."

So that's how it ended– a 41-year run of off-and-on success bookended by a pair of losses. Now the focus turns to the uncertain future of what former center Ted Jeffries once labeled "the pregnant clam."

"The thing about Mem Gym is that we kept it, and it's still appreciated for its contributions," says French, happy for the moment that the University isn't immediately cracking the clam. "And I wouldn't really call Mem Gym Jeffersonian-style architecture. It shows its time. The same with UHall."

It doesn't seem to be a matter of if, but rather when, UHall will be taken down. That will be the day when it all sinks in for Richard Morgan– when the building where he scored 39 points to beat North Carolina will be no more.

"That will be tough when they do that," says Morgan, a 1989 UVA graduate who's now an assistant coach at Appalachian State. "I know it's coming, but it's hard to get prepared for something like that. There's a lot of history in that building."

#

Chris Graham is the editor and co-publisher of Waynesboro's top blog, augustafreepress.com.

With co-author Patrick Hite, Chris Graham wrote Mad About U: Four Decades of Basketball at University Hall, which was released this month by Augusta Free Press Publishing.BOOK COVER

Balloons rise and confetti falls and the UVA men's team also falls– 71-70 to Maryland on March 5, 2006. PHOTO BY DAN ADDISON

Coach Dave Leitao waves goodbye after the "last ball," the final men's basketball game at University Hall.

UVA PHOTO BY DAN ADDISON

Barry Parkhill goes up for two during UHall's heyday.

UVA SPORTS INFORMATION

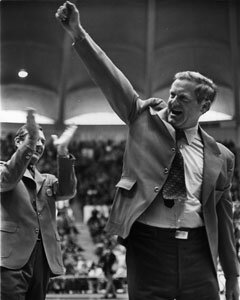

"The pressure was unbelievable," says then-head coach Terry Holland of the Sampson years.

December 1971, the month Barry Parkhill set the Virginia scoring record with 51 points in a win against Baldwin-Wallace, and just a month before the Cavs finished their first winning season in 17 years.

Governor Linwood Holton cheers in 1972.

That game against Kentucky

To-be-removed scaffolding holds up the compression ring for the concrete ribs.

October 1985: UVA president Edgar Shannon (second from right) joins xxx Gibson and Butch Slaughter.

Louis Armstrong played in 1966.

The ultra-secret Seven Society made itself known.

Exterior in 1967

Interior in 1966

UHall and the Cage were fairly lonely back then.

Muscles

Barry Parkhill, whose 1971 game-winner strengthened UHall, helped raise the money for the replacement.

September 1964

Ready for a concrete pour

Gus Tebell

Debbie Ryan in 1976

A fisheye view in 1976

The now-ostracized Pep Band in 1972

1972

SIDEBAR- UHall vs. JPJ

CAPACITY:

UHall: 8,392

JPJ: 15,219

OPENED:

UHall: November 3, 1965

JPJ: August 1, 2006

POP CULTURE AT OPENING:

UHall: "Yesterday" by the Beatles #1 on the Billboard singles charts, The Sound of Music top grossing movie of the year

JPJ: "Promiscuous" by Nelly Furtado #1 on the Billboard singles charts, Miami Vice top movie at the weekend box office

MEN'S BASKETBALL RECORD IN SEASON PRIOR TO OPENING:

UHall: The last season at Memorial Gym saw the 'Hoos go 7-18.

JPJ: After the disaster of 2004-05, the Cavs finished their final UHall season at 15-15.

CONSTRUCTION COST:

UHall: $4 million

JPJ: $130 million

ARCHITECTURE:

UHall: Cambridge, Massachusetts-based Lawrence Anderson invoked Jefferson's Rotunda in the concrete roof

JPJ: Charlottesville's own Bob Moje invoked Jefferson's red brick and columns in the concrete pergolas

FIRST GAME:

UHall: Adolph Rupp's Kentucky Wildcats stomped the Cavaliers 99-73.

JPJ: Lute Olsen's heavily favored Arizona Wildcats return three starters from last year's Pac-10 runners-up.

FIRST SEASON IN NEW DIGS:

UHall: With Ralph Sampson only five years old at the time, the Cavaliers were only 7-15.

JPJ: Dave Leitao hopes to get his team to finish above .500 for the first time since 2003-04.

FAMOUS NON-ATHLETIC VISITORS:

UHall: The Beach Boys (1971), Chuck Berry (1972), Talking Heads (1983), R.E.M. (1986), Bob Dylan (1991)

JPJ: After only a few months– Kenny Chesney, James Taylor, Dave Matthews Band, and the WWE, with Eric Clapton yet to come!

TALLEST PRESENCE:

UHall: Ralph Sampson at 7' 4"

JPJ: The 'Hoo Vision screens at 16'

HOSTING A RISE TO GREATNESS:

UHall: Michael Jordan vexed UVA as a North Carolina Tar Heel

JPJ: Robert Randolph and the Family Band's set opening for Dave Matthews Band was awesome!

FILE PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

SIDEBAR- Stacking up: other arenas in the ACC

UVA officials have frequently called UHall's replacement, the new John Paul Jones Arena, "the best place to play basketball in the country." But how does it stack up against its ACC counterparts?

BOSTON COLLEGE- CONTE FORUM

OPENED: 1988

CAPACITY: 8,606

NAMED FOR: Former U.S. Congressman Silvio O. Conte (R-MA)

FYI: It's the only basketball arena in the ACC that also doubles as the home of the school's hockey team. But then, one would expect that from the only ACC school north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

CLEMSON- LITTLEJOHN COLISEUM

OPENED: 1968

CAPACITY: 11,020

NAMED FOR: Longtime Clemson business manager J.C. Littlejohn

FYI: John Paul Jones Arena was designed with the idea that UVA would have a home court advantage with fans being so close to the court. Nowhere is that particular advantage more pronounced than at Littlejohn, where students and the Tiger Band sit right under the basket. It's said to be a big reason why Clemson has won 70 percent of its games at home.

DUKE- CAMERON INDOOR STADIUM

OPENED: 1940

CAPACITY: 9,314

NAMED FOR: Former Duke basketball coach Eddie Cameron

FYI: Cameron Indoor is easily the most famous venue in all of college basketball– due to easily the most famous cheering section in the game: the Cameron Crazies. These future doctors and lawyers paint themselves blue and white, camp out for days outside the arena for tickets, and create mayhem for opposing players on the court. And while UVA's swank new digs cost $130 million, Cameron Indoor's initial construction cost was only $400,000– proof you don't have to buy legendary status.

FLORIDA STATE- DONALD L. TUCKER CENTER

OPENED: 1981

CAPACITY: 12,100

NAMED FOR: Former U.S. Ambassador to the Dominican Republic Donald L. Tucker

FYI: Known until 2004 as the Tallahassee-Leon County Civic Center, the arena is municipally owned, and so the Seminole basketball teams have to share the space with a minor league hockey team and the likes of Cher, Hoobastank, and the circus.

GEORGIA TECH- ALEXANDER MEMORIAL COLISEUM

OPENED: 1956

CAPACITY: 9,191

NAMED FOR: Former Georgia Tech football coach William Alexander

FYI: When the Yellow Jackets aren't taking on ACC foes, this venue hosts everything from an Olympic boxing tournament to the NBA's Atlanta Hawks. With U-Hall's closing, it is now the only perfectly circular ACC arena. Although it's known as "The Thrillerdome," Michael Jackson hasn't threatened to sue yet.

MARYLAND- COMCAST CENTER

OPENED: 2002

CAPACITY: 17,950

NAMED FOR: The nation's largest cable company, that paid $25 million for the naming rights

FYI: A replacement for ancient Cole Field House, this is one of the biggest indoor arenas built in recent years. Its most prominent interior feature is the steeply sloped, 10-row student section known as "The Wall." Situated behind the visiting team's second half basket, this 2,600-seat section is a vivid example of immutable Mother Nature: the seats sit atop a hill that was too expensive to excavate.

MIAMI- BANKUNITED CENTER

OPENED: 2003

CAPACITY: 7,000

NAMED FOR: "Banking for locals, by locals."

FYI: This is the newest arena in the ACC after JPJ. However, the most significant event in this multi-purpose arena's short history actually has nothing to do with basketball. In September 2004, it was host to the first debate between President George W. Bush and Senator John Kerry.

NORTH CAROLINA- DEAN SMITH CENTER

OPENED: 1986

CAPACITY: 21,750

NAMED FOR: If you don't know this, you shouldn't be reading this page.

FYI: Though celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, the "Dean Dome" is still by far the largest arena in the ACC. Initially, it was known as one of the conference's quieter venues because alumni occupied seats that would have gone to students in other arenas. That changed in 1992 when UNC expanded student seating, helping UNC to an 220-47 all-time home record.

NC STATE- RBC CENTER

OPENED: 1999

CAPACITY: 19,722

NAMED FOR: The Royal Bank of...Canada?

FYI: With three concourses, 2,000 club seats, 75 luxury boxes, and even a 500-seat restaurant, the Wolfpack have some of the swankiest digs on the East Coast. It's also home to the NHL's Carolina Hurricanes, and it would figure that an arena named after a Canadian bank has seen more hockey-related excitement than hoops hoopla. In fact, fans in Raleigh set a world record when the noise level inside the venue for Game 2 of the Stanley Cup finals got up to 145 decibels!

VIRGINIA TECH- CASSELL COLISEUM

OPENED: 1962

CAPACITY: 10,052

NAMED FOR: Former Tech VP of Administration Stuart Cassell

FYI: If UVA is worried about how people will receive its new arena, it can take solace from the fact that almost any welcome will be better than the one that greeted their in-state rival's arena. For Tech's first basketball game in its new home, fans sat on the concrete floor because the seats had not yet arrived. Since then, the Hokies' hoops program hasn't been a powerhouse, and Cassell Coliseum hasn't become Cameron Indoor Stadium. However, the popularity of Tech basketball has risen in recent years as the Hokies have improved in their first seasons in the basketball-batty ACC.

WAKE FOREST- JOEL COLISEUM

OPENED: 1987

CAPACITY: 14,407

NAMED FOR: U.S. Army medic and Medal of Honor winner Lawrence Joel

FYI: Basketball fans filing into big echoing coliseums with popcorn and pennants in hand aren't usually thinking of our troops overseas. But in Winston-Salem, fans are reminded of those brave men and women each time they enter this arena as they pass a monument to the fallen hero who gives the venue its name. One cool aspect of the building is that with a few hundred chairs and a curtain, it's easily converted to a theater. In fact, JPJ architects liked the idea so much that they implemented it in Charlottesville.

#