COVER- Mad about you: Archie and Amélie's Albemarle

They were the Scott and Zelda of the Gilded Age. She was a scandalous author from a pedigreed Albemarle family. He was a rich-as-sin Astor, who escaped from a New York insane asylum.

Albemarle at the turn of the 19th century was no stranger to the national spotlight. It was the era that produced the beautiful Langhorne sisters, one of whom achieved worldwide fame as the "Gibson Girl," as well as the sensational case of former Charlottesville mayor Sam McCue, hanged for murdering his wife. Yet Amélie Rives and John Armstrong Chaloner really gave Virginia– and America– something to talk about.

"It has everything: sex, money, celebrity, and tangled psychological states," says Donna Lucey, whose book, Archie and Amélie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age, came out this summer. Better yet, much of the story is set in Keswick.

And yes, there's a dead body.

Jefferson slept here

Amélie Rives lived at historic Castle Hill on Route 231. Her ancestor, Dr. Thomas Walker, was a pioneer in the area, as well as guardian to the young Thomas Jefferson. Her godfather was Robert E. Lee. The beauteous Southern belle became one of the most famous authors of her day with her steamy 1888 novel, The Quick and the Dead, a potboiler that shocked the nation by implying– now hold onto your corset– that women might feel passion.

Archie was born John Armstrong Chanler, great-great-grandson of John Jacob Astor, and the oldest of 10 Astor orphans who inhabited the Astor estate, Rokeby, in the Hudson Valley. He founded the town of Roanoke Rapids, which he intended to be a model of industry near the Virginia border in North Carolina.

The two were connected to virtually everyone who was anyone in their day, including luminaries such as Stanford White, Theodore Roosevelt, Oscar Wilde, and Henry James.

Both strong-willed children of privilege, Lucey contends they were a disaster waiting to happen.

"From early on, Amélie understood that she had two unmistakable gifts– a knack for writing and a mesmerizing appeal," writes Lucey. "Men could not resist her, and she was ruthless in wielding her charm."

Archie's monied status appealed to Amélie Rives in the post-Civil War era, when the Rives family– like many others of the landed gentry– had become near-penniless aristocrats. Her marriage to Archie at Castle Hill on June 14, 1888, would provide much-needed repairs for the genteelly shabby estate.

But the marriage was not a happy one, and they spent much of it apart. For a time, the couple resided at Madame de Pompadour's chateau near Fontainebleau.

By the time they returned from France, the high-strung Amélie was strung out on morphine, and the marriage was over– though not because of her addiction. Lucey thinks it's possible, despite Amélie's fevered prose, that their marriage was never consummated.

Divorce in the Gay Nineties was a scandal to be avoided at all costs, but Amélie was willing to risk it after she found a prince– Prince Pierre Troubetzkoy. After divorcing Chanler, she married Pierre in 1896, and the press breathlessly followed the newlyweds on their honeymoon. Unfortunately for Amélie, the prince, while a talented painter, had no money, and– perhaps another indication of her mesmerizing charm– Archie continued to provide financial support to the love of his life even after she married someone else.

After Amélie's remarriage, a devastated Archie purchased another Keswick-area estate, Merrie Mill, just down the road from Castle Hill, where his life took an interesting turn. Soon he was performing psychological experiments in which he tapped into his subconscious with his so-called "X-Faculty" to produce "automatic writing," according to Lucey.

Spiritualism and seances were the rage of the day, but Archie did them one better, reportedly having the ability to go into a trance and turn his face into what witnesses described as a dead-ringer for the death mask of Napoleon Bonaparte.

All this provided the necessary fodder for his brother, Winthrop Chanler– who was also a partner in the Roanoke Rapids venture– to have Archie declared insane in 1897 and committed at Bloomingdale Asylum in White Plains, with the help of Archie's buddy, architect Stanford White, who lured him to New York.

(About this time White was rebuilding the Rotunda at UVA following its 1895 fire. His work was dispatched in the mid-1970s.)

Archie remained in Bloomingdale for four years, until he was able to escape and head back to Virginia, another national news story. At the Albemarle courthouse, he was declared sane in Virginia in 1901, but it took until 1919 to have his sanity legally certified in the rest of the U.S.

He was so outraged by the family that committed him to an insane asylum, ignored him for four years, and took control of his fortune, that he changed his last name to Chaloner– which he considered the original form of Chanler– in 1906.

Then when his brother Robert signed a disastrous pre-nup that assigned his money to an opera diva who put him on a $20 a month allowance, Archie telegraphed Robert– and the press– with what would become the catch phrase of the day: "Who's looney now?"

History of eccentricity

In the book-lined reading room at the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society, Margaret O'Bryant still chuckles over Archie's infamous telegraph. "He's been among our progression of world-class characters," she says. One of the books on her shelf actually declares that Chaloner earns "top honors for eccentricity in a county which has been home to many individuals of a similar bent."

Archie became a benefactor to the county much as Paul Goodloe McIntire was– only more fun, according to that same book, John Hammond Moore's classic history, Albemarle: Jefferson's County.

Among his McIntire-like gifts to the community, Chaloner built the county's first swimming pool at his Merrie Mill estate. "All the children in the neighborhood learned how to swim there," writes Lucey. He also turned a barn into a silent movie theater with a player piano, and opened the door to the public, reserving a quarter of the seats for blacks, unheard of during those segregationist times.

"He was really beloved by the black community," says Lucey, who describes Archie's attitude toward his integrated movie "theater" quite simply: "If you don't like it, don't come."

And his Fourth of July parties were so extravagant that the Thomas Jefferson Foundation moved its festivities to Merrie Mill in 1923, when an estimated 10,000 people attended.

But it's what happened to John Gillard in the Chaloner dining room that helped seal his place in the history books.

Attack with tongs

Lucey says that local mechanic and ex-Australian bushwhacker John Gillard was a known wife beater and an alleged terrorist to his children as well. Things reached a boiling point on March 15, 1909, when Gillard's wife sought protection– under Chaloner's roof at Merrie Mill.

That night, Gillard came over and began beating her with fireplace tongs.

Archie always carried a pistol, and Gillard ended up dead on the dining room floor. A brass star on the floor still marks the spot where he died.

There's a story that another man present at the time, John Grady, who was black, actually shot Gillard but that Archie took the fall, knowing he'd have a better chance at acquittal– and because of what Lucey calls his "romantic code of chivalry."

Archie was hailed as a hero, and no charges were ever filed against him. Of course, the shooting by an Astor heir once again made the news, causing a nephew in school at Eton to disavow any relationship to the clan, Lucey says.

But the brass star Archie had affixed to the floor suggests that he wasn't too embarrassed about the deed.

The end

In his later years, Chaloner stayed in his room at Merrie Mill. If he wasn't insane when he was committed to the asylum in 1897, he came closer to incapacity in the years following his escape, and Lucey guesses that he suffered from bipolar disorder.

The prince died in 1936, and like her first husband, Amélie became a recluse in her room, living in genteel poverty at Castle Hill, although she continued to attract literary admirers such as H.L. Mencken, Sherwood Anderson, and William Faulkner, who popped by– as did a young Katherine Hepburn, Lucey reports.

Archie died in 1935 and Amélie 10 years later, both penniless. But in Keswick, their legends live on.

Amélie Rives never met a man she couldn't charm– and her Astor husband continued to support her even after she dumped him for a penniless Russian prince.

PHOTO COURTESY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UVA LIBRARY

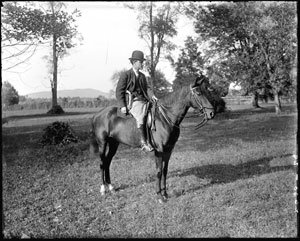

Pistol-packing Archie Chaloner made Virginia his home, even after his marriage to Amélie Rives ended in divorce in 1895.

PHOTO COURTESY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UVA LIBRARY

Archie thought he resembled the Napoleon death mask. His psychological experiments and "automatic writing" landed him in an insane asylum.

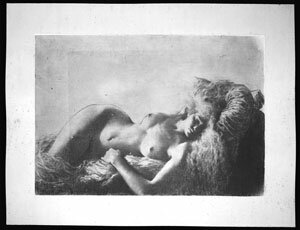

PHOTO COURTESY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UVA LIBRARY

Amélie drew this provocative self-portrait dated August 21, 1892, the same day her lover, George Curzon– who would later become viceroy to India– arrived at Castle Hill.

PHOTO COURTESY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UVA LIBRARY

Amélie Rives' homeplace is now on the market for $14.5 million. Castle Hill is on the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Landmarks Register, and its 600 acres are in a conservation easement. Amélie's beloved boxwoods remain, and she and Troubetzkoy are buried just beyond them.

PHOTO COURTESY FRANK HARDY REAL ESTATE

The historic marker at Castle Hill omits the tenure of infamous author Amélie Rives, the last Walker descendant to own the estate.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Grace Episcopal Church burned to the ground in 1895 and was rebuilt thanks to an insurance policy Archie had conveniently– and somewhat suspiciously– taken out shortly before the fire. "That would be like Archie," says Donna Lucey. "In the midst of his marriage collapsing, maybe he thought that if he saved the church, Amélie would come rushing back to his arms."

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"I am so sick of people coming here looking for Archie, Archibald, whatever his name is," grumbles a woman in the Grace Episcopal Church office when asked the location of Archie's grave. His relatives were shamed into putting up a marker two years after his death.

Merrie Mill was called the Merry Mills during Archie's heyday, and served as a community center– with Archie holed up in his room.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The brass star where John Gillard died remains in the dining room at Merrie Mill. Author Donna Lucey, left, tells how Archie sat up all night with the body, and the next morning reporters found him, dressed in leather pajamas, having breakfast of roast duck and vanilla ice cream. Archie paid for Gillard's funeral and tombstone, but was dissuaded from making "He died game" Gillard's epitaph.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The entrance to Castle Hill is on Route 231 in Keswick.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

The living room at Merrie Mill– complete with billiard table– was where Archie performed experiments with his "X-Faculty." One message from his subconscious ordered him to pick up live coals and falsely promised that he wouldn't be harmed.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Archie turned this barn into the "Merry Mills Motion Picture Theatre" and screened free silent films accompanied by a player piano.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Archie was a founder (and funder) of the Keswick Hunt Club. When the club's charter was registered in 1898, he was listed as "President: the presently incarcerated John Armstrong Chanler," according to Archie and Amélie.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

When his brother signed a disastrous pre-nup, Archie telegraphed: "Who's looney now?"

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#