NEWS- Woods wrangle: Mansion prompts conservation snit

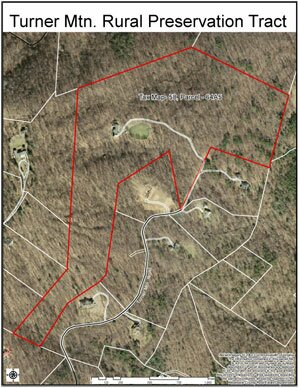

The red line restricts clearing on the 47-acre property to two acres and one single-family residence and outbuildings.

2002, COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA PHOTO

Albemarle County has long attracted its share of landed gentry, but now the land purchased by one of them is mired in controversy.

John F. Harris is a senior advisor and former chief financial officer of the Carlyle Group, a private equity firm that manages more than $75 billion (yes, billion) and boasts former President George H.W. Bush and James Baker III as its advisors.

Last October, Harris and his wife, Amy, both UVA alums (class of '82), bought a 47-acre property with a 4,200-square-foot house on Turner Mountain near Ivy for $2.1 million.

Apparently the 11-room brick mansion custom built for a horse trainer and his family of four was not quite enough for the Harrises and their two children. They obtained a building permit for a 19,500-square-foot house– nearly 2,000 larger than Patricia Kluge's Albemarle House– to make chez Harris one of the largest– if not the largest– houses ever built in the county.

But what's so wrong about living large? Just one thing: the property lies in a conservation easement.

And yet the new family on the block seems to have followed many of the rules, and Albemarle issued the building permit September 7. Shortly thereafter, neighbors reported hearing ominous sounds of timbering. And consternation ensued.

"When we began to hear so many chain saws in the area, we became concerned," says neighbor Harvey Wilcox.

They alerted Ivy's supervisor Sally Thomas, county officials, and the Piedmont Environmental Council. By September 17, inspectors were on the scene, and on September 18, the county issued a stop-work order and revoked the building permit.

In 1992, the land on Turner Mountain Wood Road was put in one of the county's earliest conservation easements, which allow clearing of only two acres and restrict development to one single-family dwelling and outbuildings, according to county spokeswoman Lee Catlin.

"The new folks wanted to build a 19,000-square-foot house and classify the old house an outbuilding," she says. And if the stove was removed, "Our staff determined it could be considered an outbuilding."

With granite kitchen countertops, a baronial living room, and a grand staircase with custom-forged ironwork, that's one special outbuilding.

"On the face of it, it's ridiculous," says Sally Thomas, who acknowledges that the practice of removing a stove to comply with zoning laws is a common throughout the state.

"The issue we're hanging our hat on," explains Thomas, "is the fact that the acreage allowed to be cleared has been exceeded."

Indeed, the building permit issued by the county okays clearing 1.7 acres. Since one acre is already cleared for the existing structure and the permit number is cumulative, says Catlin, the total would violate the conservation easement's two-acre limit.

So how was a building permit issued in the first place? Before a permit is issued, explains Catlin, the zoning department does a review. "That's where the breakdown occurred," she says.

Neither the Harrises nor their attorney, James E. Treakle, returned phone calls by press time. However, in a four-page letter distributed in the Turner Mountain Wood subdivision, the Harrises explain their project and their hopes for neighborly relations.

Before even buying the property, they approached both the county and the conservation easement holder to make sure they could build a new house, they write, "and received clear confirmation that in fact we could do so."

They were told they could live in the existing house while the new one was being built and keep the old house by removing the refrigerator and range, according to the September 17 letter.

"Prior to signing our construction contract, we reconfirmed our plans and these conclusions with the County and received the approval of the Albemarle County Attorney to proceed," the Harris letter continues. "...It is our full intent to build a home that fits the great character and style of the neighborhood."

"Nineteen-thousand-square-foot houses are unheard of in this neighborhood," says Harvey Wilcox, once he stops laughing. He describes the typical house in the Turner Mountain area as cedar sided, unobtrusive, and back-to-nature.

This particular easement was one of the first in the county and was applied to the original subdivision on Turner Mountain Wood Road by UVA professor Richard Selden and his wife, Martha, an ardent conservationist. Although noting that early easements aren't as "artful" as the ones drafted today, Wilcox is mad that Mrs. Selden's intentions are being challenged 15 years later.

"I'm bothered as heck," says Wilcox. "If it's not in perpetuity, why bother? This cuts the legs out of [conservation easements]," he says. "Hire some fancy lawyer. Take out the stove and call them outbuildings."

"The thing I think is important is the end result," says Rex Linville, a land conservation officer with PEC. "The county did exactly what they should do. They realized it was a problem and acted on it."

This is a county, after all, that takes conservation easements so seriously that it spends millions funding a program to protect more land.

"We fight very hard to maintain those," says Thomas. "A number of people said this would be a bad precedent for conservation easements."

In their letter, the Harris family apologized for any truck traffic and offered to hold a neighborhood party when construction ends. Some neighbors hope it has already ended.

[The headline in the print version of this story was incorrect, it has been corrected in this online edition.]

#