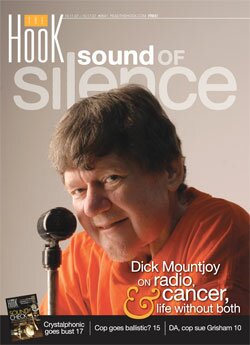

COVER- Sound of silence: Dick Mountjoy on radio, cancer, and life without both

"Aaall riiight now, baybee, it's aaall riiight now!"

"Aaall riiight now, baybee, it's aaall riiight now!"

For a moment, Dick Mountjoy is back in his element. Surrounded by walls of vinyl records, he grins as he strums an air guitar, and the signature riff by British rock band Free takes him back to 1970, when the song was a hit and Mountjoy was a 24-year-old disc jockey and radio station music director.

But it's 37 years later. The song has come on during a commercial break from a football game, and the voice that will be back after these words from the sponsor will not be his. Instead, Mountjoy picks up a pen and continues to jot down a story about his radio heydays.

Such is Mountjoy's new life. For the last six months, the owner of the most famous voice in Charlottesville radio has been learning to live without it.

A sore throat

In the fall of 2005, Dick Mountjoy was feeling better about his health than he had in a long time. A large man whose weight had peaked at 430 pounds, he had recently been taking better care of himself.

"I had become what they call 'morbidly obese,'" he says.

(These days Mountjoy doesn't actually "say" anything; he communicates by writing or typing.)

"I had been trying to lose weight for about two years," he says, "and in early 2005, it was working." He had dropped 70 pounds and felt "in control for the first time in decades."

However, the cooler months had historically been unkind to the morning radio host's voice, and he wasn't looking forward to fall.

"I was certain I could expect my annual bout with a sore throat, leading to laryngitis, often resulting in losing my voice and missing a week's work," he says. "Sure enough, it was beginning once again."

But by December, it became clear that this wasn't just the usual mean season. His throat was hurting in a new way, and he could tell it was affecting his work. By January, others began to notice.

"It sounded like he'd had a stroke," says Jane Foy, his longtime co-host at WINA 1070. "I'd noticed, and then listeners started to notice, and they began e-mailing and asking what had happened."

Stumped but suspecting sinusitis, the doctor referred Mountjoy to a specialist, and after a series of tests, including a look inside his throat via fiber optic cable, sinusitis was the official diagnosis. He began taking a prescription, but the symptoms persisted.

"My speech was failing, and my eating patterns had changed because it was so painful to swallow," he says. "So he offered yet a different prescription, and I was going to be taking something for the supposed acid reflux."

Mountjoy's radio work continued to suffer.

"The morning show was becoming a struggle," he says. "I would recuse myself for long segments. I mostly just operated the board, minding the microphone switches, airing commercial breaks, and bringing in local and CBS newscasts. I was fast becoming useless."

After a third visit to the specialist and a third, deeper, look inside Mountjoy's throat, the doctor found something at the base of his tongue: a tumor the size of an egg.

"I was actually relieved," says Mountjoy. "Now I knew we were finally getting somewhere."

The voice of Charlottesville

Mountjoy made his Charlottesville radio debut in July 1965 as an 18-year-old rising second-year at UVA. He worked part-time spinning Top 40 hits for what was then Charlottesville's leading music station: 1010 AM WELK. Being on the air for a real radio station was a dream he'd had since his visits to grandparents' house in Stafford County, where he listened to Amos n' Andy and Elvis Presley on their old living room console.

"It was magical," he says. "All that entertainment coming from who knew where."

Soon he worked his way through the ranks to became WELK's music director, and as such he was responsible for introducing late '60s-early '70s Charlottesville to the latest music from England, Motown, Memphis, Haight-Ashbury, and all the other places that produced the soundtrack of that legendary era.

All this extracurricular activity, however, came at the expense of his studies at the UVA engineering school, and he flunked out in 1966.

He briefly considered returning to his studies when his grandmother "offered to pay for everything if I would agree to enroll in a new computer school in Richmond," Mountjoy recalls. "I told her, 'I appreciate that, Grandmommie, but this whole computer thing will never amount to anything.'"

After passing up that potential fortune, and after a failed physical kept him from going to Vietnam, Mountjoy returned to the Charlottesville airwaves– and proceeded to make them his home for 39 years.

On WELK, Mountjoy spinning a steady stream of the latest chart-toppers was a constant in an increasingly turbulent world. Only 18 months into his professional career, it fell to Mountjoy to steer his audience through a tragedy.

"On a Friday evening in January 1967, I was sitting in for someone else's shift when the AP wire machine rang its bells," he recalls. A flash fire inside the Apollo 1 capsule had killed astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee.

"It's always difficult deejaying a music show at moments like that," says Mountjoy. "I was a young pup, barely 20 years old, but I guess I did okay."

It wasn't long before the "young pup" began mentoring an aspiring disc jockey who arrived at the station in 1971. His name was Dick Bartley.

Four years later, Mountjoy saw his young prodigy make the leap from Charlottesville to the big leagues in Chicago, and eventually to a career hosting the nationally syndicated oldies programs, American Gold and Rock & Roll's Greatest Hits, culminating in 2000 with his induction into the National Radio Hall of Fame.

"What Mountjoy taught me most of all was to have fun," says Bartley. "We all have access to the same records, so it's what you do in between the songs, how you bond with the listener, that makes the difference."

"He's my proudest success," says Mountjoy. "I was just happy to be there at the creation of a superstar."

Bartley says he sometimes thinks about how Mountjoy could have enjoyed the same fame.

"He had the talent to go on to larger markets," says Bartley. "But he loved Charlottesville. He made a choice that he was committed to this community, and I always admired that about him."

That commitment allowed Mountjoy to land softly when WELK collapsed in 1980, overtaken by the new album-rock format of WWWV on the new FM dial. No more than 24 hours after WELK was off the air, Mountjoy had an offer to join the on-air team at WINA, where he remained for the next 26 years.

By the time Foy joined him as co-host of the morning program in 2001, which was briefly called "Phone with Dick and Jane," it was clear he was still having fun.

"I've been in radio 35 years, and I can count on one hand the number of people I was excited to work with every day," says Foy. "He's entertaining, he's funny, and there's a trust factor there that we're in this together."

In his darkest hours, Mountjoy would find that many of his listeners felt the same way.

The fight begins

On April 11, 2006, Mountjoy left the morning show early for his biopsy at Martha Jefferson Hospital, optimistic that this would be the beginning of the end of his illness. It wasn't.

"You could feel the tumor if you stuck your finger back there," says Dr. Paul Levine, chairman of head and neck oncology at the UVA medical center. "This was an extensive cancer."

When Mountjoy's family doctor had first checked it out, he asked if Mountjoy had ever been a smoker.

"I did test out a pipe for a few weeks my first year at the university," Mountjoy says. "After a while, I realized it was too much work, and it annoyed some people, so I dropped it."

As the treatments added up, so did the medical bills. After years of living on his disc jockey's salary and his wife's pay from her work at Sun Trust, Mountjoy was finding it hard to make up what his insurance company wouldn't cover.

So his colleagues at WINA decided to do what they could.

"People kept calling and e-mailing to ask, 'What can we do?'" says Foy. "We would say that Dick always appreciated cards and letters, but then we came up with the idea of this fundraiser to give people something to do."

"When they first pitched the preliminary plan to me, I winced," says Mountjoy. "Begging for help for one of our own was tacky and embarrassing– and even improper."

However, once he faced the prospect of having to sell his house, Mountjoy reconsidered. On July 27, 2006, WINA and all the other Charlottesville Radio Group stations– as well as Channel 29 and the Newsplex television stations– broadcast a fundraiser all day from the Fashion Square Mall parking lot. Too weak to attend, Mountjoy sat anxiously in bed in his basement.

"I was very worried that nobody would show up," he says. "But after witnessing the blanket coverage on the radio and on TV, all the flattering testimony about me, I began to be more hopeful. Then, I was in tears when they reported that the estimated total had climbed above $10,000. It was overwhelming."

By the end of the day, Mountjoy's fans had given over $30,000.

All the while, WINA was still holding out hope for the big man's return to the morning show.

Jay James, programming director at the time, says, "The understanding was that it was his job, and we would wait as long as he felt like he could come back."

The fall found Mountjoy in good spirits that even a near-accident pedestrian encounter with a delivery truck couldn't break. After the truck came to a screeching halt, all Mountjoy thought of doing was checking on the driver.

"I just smiled up at him through his open door, touching his arm, and said, 'It's okay, man. I just beat cancer, so this is nothing.'"

Signed off

By this winter, Mountjoy had gotten used to the life of a cancer survivor. He still couldn't swallow much more than soup or Jell-O, but that also meant that he continued to lose weight. The regular visits for biopsies to UVA Hospital's oncology department had become routine. So, on the afternoon of Monday, February 19, there was no reason for him to expect that things would take a turn for the worse.

But when the results came back that afternoon, Levine informed Mountjoy that the cancer had returned.

"'Oh no, oh God,' I thought. We were just numb," he says.

Eighteen hours later, Mountjoy took to the WINA airwaves. In a voice alien to listeners but now all-too-familiar to his colleagues, he shared the bad news, but also spoke of how his disease had changed him for the better.

"I have accepted love from people I didn't know were there, I have expressed love to people I did not express before, and it has helped to make my last few months unforgettable," he said, trying to enunciate each word as well as his failing jaw and tongue would allow.

"So, in my particular case, I do not necessarily hope for a cure for cancer for me, because, in truth, simply put, in my life, cancer has cured me."

Soon, it became clear that the only option left to fight the cancer was to remove the tongue and voice box of one of the most famous voices in Charlottesville. Despite the fact that it would mean he would lose his voice forever, Mountjoy says that the choice was easy because it really was a matter of life and death.

"No one would favor this, and I don't enjoy doing this operation," says Levine, "but Dick understood all the repercussions. He felt that every day was a prize, and he was willing to forego those organs to be a prizewinner."

The tragic irony of a radio man losing his voice was not lost on Mountjoy.

"I wondered," says Mountjoy. "Was it something I said? I was certain God was winking at me."

The news hit those who had worked with the radio veteran especially hard.

"I was just sick," says Foy. "I still can't make any sense of it."

"His whole life had been radio," says James. "To go from being one of the most recognizable voices in Central Virginia to not being able to speak at all– the finality of it was sobering."

"With what he means to that town, to have his voice taken away is just not fair," says Bartley. "I was deeply sorrowful for him, and a little angry."

So was Mountjoy. He says he asked God why he couldn't have sent the tumor somewhere else in his body. But, "I never got an answer," he says.

Doctors set Mountjoy's surgery for April 13. The morning before, he made his last appearance on the WINA airwaves on his old show with Foy and interim co-host Rob Schilling.

Mountjoy confesses that his last spoken words were probably just "small talk" with his doctor, but he made sure his last words to his wife, Susan, were well chosen.

"I love you," he said. "Don't worry. I'm going to be fine."

The 'new normal'

Approaching the six month-mark since his operation, Mountjoy says he doesn't look back.

"That voice served me well for all the best years of my life, but I had given 41 years to the radio microphone," he says. "I was fearless about death, I embraced every moment of life, and, God bless me, my brain still functioned."

Today, he's getting used to what he calls his "new normal." In addition to his voice, he's lost his senses of taste and smell, as well as much of the use of his left arm, due to surgery to repair a leak in the side of his neck that required moving his pectoral muscle upward.

He breathes through a hole in his throat. And having lost the ability to chew and swallow, he's now accustomed to feeding himself a diet of a nutrient-rich Nestlé product called "ProBalance" through a tube running directly into his stomach.

For a time, Mountjoy looked for a manmade substitute for his natural vocal cords to get back on the air. Without a tongue to form the words, an artificial voicebox was not an option, but computer programs that could work from a database of recordings of Mountjoy's radio voice might be. Eventually, though, he decided the concept didn't suit him.

"I'd rather have our listeners remember me as I always was, not as a mechanical curiosity," he says. "I just don't think it would wear well."

The former radio man says his new communication medium has made him a more thoughtful person.

"I used to, as they call it, 'blurt,'" he says. "Now, having to communicate in writing, that's not even possible. My life is more measured, more 'purposeful.'"

Still, it's a burden for him, and it's strange having "conversations on paper," says his wife. "There are moments when he has little temper outbursts when he's frustrated that he can't communicate what he wants to say."

Radio dreams

The good news has been in short supply, though Mountjoy is proud to note that he now weighs 230 pounds– 200 less than his heaviest weight. He even confesses to having a few radio dreams.

"Earlier this year, I dreamt that WINA was doing a morning remote," he says. "At the 6:10 open, I looked at Jane as if to say, 'Let's try this baby out.' I turned on the mike and clearly said, 'Good morning, Charlottesville.' I smiled, happy that my voice actually worked again."

Such a miracle scenario may never play out in real life, but Mountjoy has found solace in training a new Australian shepherd puppy named Boots. He currently spends his time doing chores around the house, visiting friends, and beginning the process of cataloguing all of his old LPs, which he may sell to help with his medical expenses.

The long-term prognosis for the 61-year-old Mountjoy remains unclear. Levine refuses to quantify his chances of survival or estimate how long he might have, but he concedes, "I think it's safe to say the more extensive any type of cancer, the greater the likelihood of disease."

As far as Mountjoy's next career is concerned, his former radio colleagues are unanimous.

"He ought to take that creative spirit with which he used to communicate and turn it into writing," says Bartley.

"I definitely think writing is in his future," says James. "He's still a news junkie, and his interests are so broad. He could do books, he could do commentary, he could do anything."

"I hope he writes somewhere, anywhere," says Foy. "If he wrote about this experience, it'd be a pretty good book."

The idea of a book has intrigued Mountjoy for some time.

"In my seemingly endless downtime in rehab, I conjured an outline for a book," he says. "I might call it Drive Time: Or You Can't Blow Your Nose Through a Hole in Your Neck. It was an anatomical fact I stumbled upon and a title that made me laugh. Well, silently."

#

A young Dick Mountjoy mans the phone lines at WELK circa 1967.

COURTESY OF DICK MOUNTJOY

Mountjoy spent many an hour spinning the Beatles on WELK. The old studio now serves as the home for Chaps Ice Cream.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

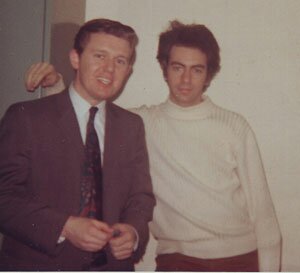

Backstage at University Hall with Neil Diamond in January 1968

COURTESY OF DICK MOUNTJOY

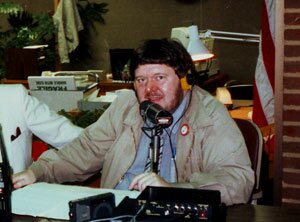

Mountjoy on the air in the mid-'90s

COURTESY OF DICK MOUNTJOY

Mountjoy rocks out with the UVA Marching Band at a men's basketball game in November 2006. Prior to his cancer, he had been the stadium announcer for the band at football games.

COURTESY OF STEVEN WINFIELD

#

8 comments

Lindsay, or "the inestimable Mr. Barnes":

Thank you for a fine piece on Dick Mountjoy.

We have great respect for him and his work.

He was recently with his son Mike at Buford

Middle School and Mr. Moore came home very

moved with the opportunity to see him after

such a long time. This article means a lot

to people who listened to him and think of

him as a friend.

The Moores

I first knew Dick when we all entered U.Va. in 1965. We remained friends for years- him always in the station window, always on the radio, always the great guy I felt a special bond with from those early days. Lives moved on, and I didn't see Dick again until 1997, when I took my sons to Charlottesville to see U.Va. There was Dick, still in the station window; a bigger star, but the same kind man with the winning smile and great heart I knew from 25 years ago. Ten years have passed since I was in C'ville. But a chance phone call to my office in Florida two months ago and the years faded away. Dick was on my email and it was 1965 and the Four Tops were in town again. But then the story of illness were unfolded to me, told by a friend to a friend. His suffering and heartache were revealed to me. And his faith, spirit and resilance were all over the page of text, but his voice was crystal clear. I hear it as I write this; the Southern boy mannarisms, the laugh that punctuated his joy of life, and the clarity of heartfelt concern for his community. This voice will never be stilled. Anyone who knows the man will hear him loud and clear.

I was a DJ at WELK in the early 70's. It was my first full time radio gig fresh out of high school. Dick Mountjoy took me under his wing and showed me through his personal example what a GREAT radio announcer has to do to survive. He taught me well. I survived 25 years in radio thanks to him. Dick is a survivor too. He will continue to inspire others through his example.

Stephen Hydrick, formerly "Steve Shannon"

I never had the opportunity to meet Dick Mountjoy. However his son, Mike was one of my best friends in college. I probably know more of the intimate details of Mr. Mountjoys life than he cares to share thanks to Mike. I have fond memories of Mike and his stories of his dad on the radio. Both of you have my prayers and best wishes for a continued long and productive life.

The passing of Dick MountJoy this morning 3/26/08 is one the hardest pieces of news I've ever had to hear.

I can hardly believe it.

Steve Shannon

Much prayers for the family and friends. I was born and raised in Charlottesville, and graduated in the 70's from Charlottesville High School. It was there, that i started my choreography career, while listening to Dick Mountjoy playing the top hits. I listened many times to him and the music while sitting down developing steps to music for my dance performance. Even though i am in the medical profession now, i am still a part-time choreographer here in Texas. I remember Mr. Mountjoy well, and i hope Charlottesville realizes his great contributions. I wish i could be there to give his family a hug. May God bless all of them--------Ruby Brown ( Texas )

I was a dj in Richmond from '67-'74 and though I never had the pleasure of meeting Dick I was aware that a great voice filled the airwaves on the other side of Afton Mountain. Mr. Mountjoy's life is a "Profile in Courage" and it's wonderful believing that, throughout this universe, his voice will continue be floating through eternity. God bless his family and legions of fans.

In town for my first visit sicne leaving C'ville two years ago, I was wondering why Dick wasn't on the morning show today, so I found this article.

Dick, as a former DJ and time salesman, I always appreciated your work. Your morning show was in some ways a throwback to the best days in radio, but it also managed to feel up-to-date.

Thanks for all you've done for this community and best wishes.