COVER- Back story: 20 years of stars, screenings and survival at the Virginia Film Festival

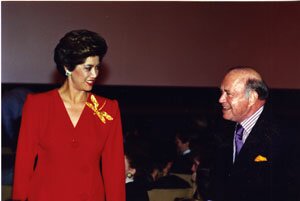

Power couple Patricia and John Kluge hosted a party at the first film festival in 1988 and contributed cash and connections that helped get the event off the ground.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

We take it for granted every fall that Charlottesville will be awash in cinema, and like clockwork, this year the 20th Virginia Film Festival opens November 1.

But that wasn't always the case, and for much of its history, the year-to-year survival of the festival was far from a sure thing.

Worries plagued the enterprise at the beginning. Chief among them: how does a university without a major film studies program come to host a film festival, and could it– or should it– continue to draw the star-studded lineup it produced its first year?

"It's almost like it was born fully grown," says festival director Richard Herskowitz, who was running Cornell's film society in 1988, but who remembers seeing festival materials from Virginia. "They made a splash in the film world immediately."

When the festival launched in October 1988, organizers had locals doing double takes. As if by some special effect, Robert Altman, Ossie Davis, and Nick Nolte all appeared in Charlottesville. Norman Mailer joined Jerzy Kosinski and William Kennedy on a screenwriter's panel. Locals Sissy Spacek, Ann Beattie, and former local Earl Hamner lent their star power to the event, as did Hollywood producers Samuel Goldwyn Jr. and Mark Johnson.

That first festival premiered two films destined to become classics: Child's Play– which spawned the whole Chuckie-the-killer-doll empire– and Mystic Pizza, which launched the career of Julia Roberts.

Beyond that bit of movie history, those four days in '88 launched another classic Charlottesville tradition: the festival itself.

But as hard as it is to believe now, not everyone thought that the Virginia Festival of American Film, as it was called back then, was a good idea.

Man with a plan

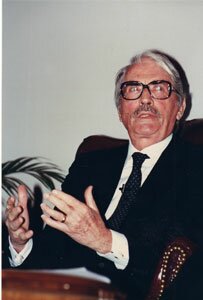

The players who got that first festival off the ground all credit one man for coming up with the seemingly crazy idea of bringing Hollywood to a small college town: Gerald Baliles. As governor from 1986 to 1990, Baliles earned a reputation for economic development and education, and the Virginia Film Festival is one of his less-heralded accomplishments.

"About a million years ago as a young legislator," says Baliles, who now heads UVA's Miller Center, "I was struck by a newspaper article about a film company that left 40 percent of its budget in the Hampton Roads area. I was intrigued."

As far back as the late 1970s, Baliles began noticing that other states, like neighboring North Carolina, had film offices, and he recognized the correlation between movies and tourism.

"I introduced legislation to create a Virginia film office," he recalls, "but the bill was killed as something new and unnecessary."

But Baliles had also tacked on an overlooked amendment to the budget that stayed, and in 1980, the Virginia Film Office was created. The idea, he explains, was to catalog the Commonwealth's assets with pictures of houses, public buildings, and scenery designed to lure filmmakers.

"You really have to woo these people," says Baliles. "The question is, how do you promote your state when everyone else is doing it?"

Around 1986 or so, he says, "I began to ruminate how, in discussions with members of the legislature and John and Patricia Kluge."

In the late 1980s, billionaire John Kluge owned historic Morven in Albemarle. He was named the richest man in America by Forbes magazine in 1987, after taking his conglomerate, Metromedia, private and selling off its television stations to Rupert Murdoch to create the Fox network.

"The question came up, what place in Virginia might attract filmmakers?" recalls Phil Nowlen, then dean of UVA's School of Continuing and Professional Studies and now head of the Getty Museum's Leadership Institute. "Charlottesville came to mind."

The location neatly connected economic development with academics and "film as the art form of the 2oth century," says Nowlen.

Baliles persuaded the General Assembly to throw in some taxpayer dollars, and the Kluges to host a reception at the inaugural festival. "We went to Hollywood to promote the festival, and I persuaded [Waltons creator] Earl Hamner to come," says Baliles. "Out of that came the first festival."

Robert O'Neil, who was president of the University of Virginia in 1988, attributes the festival's early success to three factors: Baliles' support, the number of UVA grads working in Hollywood as directors and producers, and the "strong backing of Patricia Kluge," who encouraged producer and Orion co-founder Mike Medavoy, with his vast Hollywood connections, to join her on the festival's advisory board.

Also on the board were veteran producer David Brown (Jaws, Cocoon); Jack Valenti, the late longtime president of the Motion Picture Association of America; former Richmonder Shirley MacLaine; Spacek; American Film Institute director Jean Firstenberg; and UVA grads Goldwyn and Lewis Allen, producer of many Broadway hits, including Annie.

In the summer of 1987, recent UVA graduate Bob Gazzale found himself invited to a meeting at Carr's Hill, the hilltop home of the UVA president.

"It was as if the university had marshaled the forces of the universe," says Gazzale, who later became festival director and who credits Patricia Kluge for providing the "spark" that brought people to the table– at least in the first few years.

Now a winemaker, Kluge is too busy to talk about the early days of the festival, according to an assistant.

The Cannes Film Festival takes place along the French Riviera in May, and Sundance happens every January in Park City, Utah, at the height of ski season. To Gazzale, now president and CEO of the American Film Institute, a festival amid the autumn foliage in Central Virginia created similar perennial appeal.

"Just as Charlottesville drew Jefferson," says Gazzale, "it's no secret the great film festivals happen at gorgeous places at the right time of year."

But as festival organizers would later find, there can be thorns in that foliage.

Going Hollywood

Affable creative writing professor George Garrett remembers the first festival. "We weren't able to get that much new stuff at the beginning because we didn't have a track record," he says. "We were giving awards. That's the way we made up for the absence of world premieres. People will come a long way for an award, so we were passing out awards like crazy."

Indeed, that first year Robert Altman received a Distinguished Filmmaker Award, and Frederick Wiseman took home an award for excellence in documentary filmmaking.

Garrett remembers a meeting in which Patricia Kluge arrived with a man wearing a tweed jacket. "He looked like a professor," says Garrett. The unknown gentleman, seated beside Kluge, reached inside his jacket, pulled out a comic book, and started reading it.

"He was being really rude," says Garrett. A few minutes later, Kluge asked the man to go do something, and Garrett spied a gun on the guy.

"He was the bodyguard dressed up to look like a professor," laughs Garrett, "and he looked more like a professor than we did." (A former Kluge bodyguard, Dorian Lester, murdered a Charlottesville jeweler in 1997 and is now serving a life sentence.)

In 1993, film noir was the festival theme, and Garrett was teaching a film class. He assigned his students to attend one event at the film festival and get one autograph. "A lot of people who never thought of themselves as stars had 50 people trying to get an autograph," he chuckles.

The holy grail of autographs at that festival was Robert Mitchum's. One of Garrett's students was a waiter at the opening gala, and according to Garrett, Mitchum told the student to "keep those martinis coming." At the end of the evening, Mitchum gave the student an autograph, and Garrett gave him an A+.

The second Virginia Festival of American Film upped the star power with Hollywood legends Jimmy Stewart and Gregory Peck in 1989. Both men had avoided Hollywood scandals, and offscreen both were family men, but their politics were quite different.

"They barely spoke to each other," recalls O'Neil. "I remember standing in the front hall of Carr's Hill trying to get them to talk." The ice finally was broken by O'Neil's two sons, one of whom attended Stewart's alma mater, Princeton, and one Peck's, UC Berkeley.

Charlton Heston arrived a day late for the 1991 festival, which included screening of a "gorgeous print" of Ben Hur, remembers Gazzale. Still, he could tell Heston was a tad ill at ease.

"He said to me, 'I have a serious problem.'"

Gazzale braced himself for the bad news.

"I left my ChapStick at home."

Gazzale sent a student runner out to return with a box of ChapStick. When Gazzale offered to reimburse the student, "He burst into tears," Gazzale says, "and said, 'I just bought ChapStick for Moses.' And that's a wonderful example of how these people affect us."

Finding a home

Once UVA got the nod from the state as festival host, the next question was, where would it reside within the university? The first stop was the English department, where Wendy Goodman, the festival's first director, was on the faculty.

"Over time, it was clear the English department was not set up to weather the politics or logistics of such an event," says Tim Scovill, who was an associate dean in the School of Continuing and Professional Studies at the time.

The festival then moved to the McIntire School of Commerce. "They thought, 'It needs management; let's send it to a place with management,'" Scovill explains. "One month later, it was clear they weren't able to handle the logistics or the politics."

UVA's Division of Continuing Education became the festival's headquarters for the next few years. "We had the structure and the organization to handle it politically and logistically," says Scovill.

While then-President O'Neil and the governor lent political and financial support and the Kluges kicked in a quarter of a million dollars, Scovill remembers constant debate over whether UVA should be in the festival business– and envious departments within the university weren't the only doubters.

"We spent a lot of time answering questions from a hostile press," says Scovill. "The Richmond Times-Dispatch regularly took the festival to task for being a toy of the benefactors. They also questioned the state support. There was no understanding of the economic development foreseen by Governor Baliles.

"We spent a lot of time generating a lot of reports justifying the festival," he adds.

And just like any big-screen production, the early festival hit its share of the behind-the-scenes snags. Even for Continuing Ed, which had conference-planning experience, logistics were a burden. Tickets needed to be sold and venues located– often places that had never before shown films. They even had a few brushes with the law.

"A number of times, police showed up [at Continuing Ed] in Zehmer Hall because all the lights were on at night when we were dealing with the West Coast," Scovill says.

Continuing Ed provided the connections for film reviewer Roger Ebert, who first appeared in 1992.

"Phil Nowlen came from the University of Chicago," says Scovill, as did another dean, Joyce Feucht-Haviar. "Both had known Roger Ebert, who had participated in continuing ed in Chicago. They called Ebert and said, 'Come to UVA.'"

After that first appearance, where he led an analysis of Citizen Kane, Ebert became a festival fixture for years with his shot-by-shot discussions of classic films.

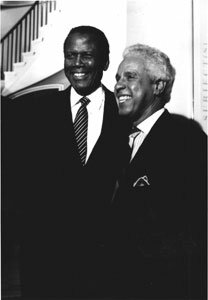

The early '90s marked the salad days for the fest. The 1992 lineup included writers Horton Foote and William Styron, historian Bill Ferris, folk artist Howard Finster, and megawatt star power in the form of Robert Duvall and Sidney Poitier.

Ebert returned the next year, bringing gravel-voiced icon Mitchum for an on-stage interview. Ebert was back again in 1994 to walk audiences through Vertigo and his own screenplay-turned-cult-classic, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.

In 1995, Fay Wray strolled across the stage of Culbreth Theater before a screening of the original King Kong.

But by the following year, it seemed that the festival was on the chopping block.

Benefactors back out

The Kluges divorced in 1990, ending the billionaire's financial participation in a project so closely associated with his ex, but Patricia Kluge continued to contribute on a more moderate scale– about $50,000 annually, according to reports at the time. The early 1990s were a time of financial crisis in Virginia: amid a recession, state spending came under tight scrutiny. Even as state coffers rebounded in 1996, Governor George Allen was not the annual festival presence that his predecessors Baliles and Douglas Wilder had been.

A new director, former Metropolitan Opera director Hugh Southern, was hired to raise private money, but he met with resistance and recommended restructuring.

By 1995, Kluge money had run out, Continuing Ed had a new dean, and there was pressure to explain why, even after all the donations and sponsorships, the strapped department should be subsidizing movie screenings. The Virginia Film Festival was at a crossroads. The options were to shut it down or move it to another department.

As a stop-gap measure, drama department head Bob Chapel stepped in, and ArtsDollars contributed to a slimmer festival. Its budget dropped dramatically, from $600,000 to $200,000. Richard Herskowitz was appointed to a faculty position and named head of the festival, and the focus on American film was removed. In 1996, the event became the Virginia Film Festival.

It's academic

Gazzale believes it's the academic setting that lures screen greats to Charlottesville. "It's all too rare that the talent shares their movie with an audience," he says. Jimmy Stewart stayed to watch Mr. Smith Goes to Washington with the Culbreth audience, and Gregory Peck took in his performance in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Unlike others, the Virginia Film Festival provides a place for filmmakers and scholars to come together and talk about film, "a remarkable gift," says Gazzale. "It's how the movies have shaped our popular culture."

In the late 1990s, Richard Rountree, the actor who played "Shaft" in the popular blacksploitation series, was on the scene. In 2002, one of Hollywood hottest (and briefest-lived) couples came to Charlottesville: Nicholas Cage and Lisa Marie Presley.

But beyond the stars and even the panel discussions, this festival has another unique hook: themes. This year it's "Kin Flicks"; other years have focused on music, faith, the South, and film noir.

"In those early years," says Herskowitz, "there was more emphasis on genre. With me, they've been more conceptual." Think "Wet," "Cool," or "Speed."

"It's a four-day course on a cultural theme in which the world is invited to enroll," Herskowitz says.

Ironically, the university now contributes 40 percent of the festival's $500,000 budget, nearly double the dollar amount of the UVA subsidy back in the festival's near-death days of 1996. (The balance of funding comes from government, corporate, and private support.)

After a six-year sojourn in the drama department, the festival was installed in the dean's office of the College of Arts and Sciences around 2002, and as the university began building a media studies program last year, the festival moved once again.

Today the festival is a year-round arts organization under the media studies umbrella, with a film society and educational programs. "In many ways," says Herskowitz, "the film festival is the culminating event."

These days, the value of the Virginia Film Festival to UVA, Charlottesville, and the state isn't questioned, and Tim Scovill observes the changed landscape. "People aren't asking those critical questions, and it's because it has succeeded."

Southern hospitality

So who was the worst-behaved celeb to grace the Virginia Film Festival? Herskowitz hesitates, and then names 2003 guest John Wojtowicz, the real-life bank robber (who might not even count as a celebrity) who became the inspiration for Al Pacino's performance in Dog Day Afternoon.

"Behind the scenes, he made life hell for us," says Herskowitz, who claims that Wojtowicz, who died in 2006, demanded a wheelchair and had someone wheel him around the whole festival. Then at the closing night party, says Herskowitz, "He got up and danced."

As much as Wojtowicz put festival organizers to the hospitality challenge, "On stage, he was eloquent and very moving, and I was glad we invited him," Herskowitz says.

That southern hospitality is perhaps another of the Virginia Film Festival's charms.

"I remember very clearly at the end of the first festival when the late Jack Valenti said, 'I've been to a lot of festivals over the years, and I can't think of one that provides better organization and hospitality for its guests,'" relates Tim Scovill, who got married the morning the second festival began and was congratulated by Jimmy Stewart and Gregory Peck.

Headline guests stay at the Boar's Head Inn and are assigned drivers. "Charlottesville is a great city for movie stars," says Scovill. "They don't get manhandled. They don't get ogled. People are very respectful."

How does the Virginia festival, now in its 20th year, stack up against other festivals?

"It's considered one of the gems," says Gazzale from atop his perch as director of the American Film Institute. "It's unique. It's not trying to be Cannes, it's not trying to be Tribeca. It's comfortable in its setting: Thomas Jefferson's Academical Village."

One tried and true way of luring stars is to hand out awards, organizers learned early on. Arlington native Sandra Bullock received the Virginia Film Award in 2004 before the screening of Miss Congeniality.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

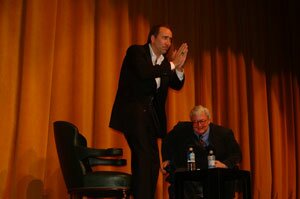

Nicolas Cage screened his directorial debut, Sonny, at the 2002 festival and was then interviewed by Roger Ebert, who skillfully avoided offering an opinion on the film.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

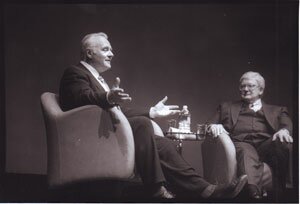

Another award, another Ebert interview: Academy Award winner Anthony Hopkins had people clamoring for tickets at the sold-out screening of Titus at the 13th festival in 2000, when Hopkins received the Virginia Film Award.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

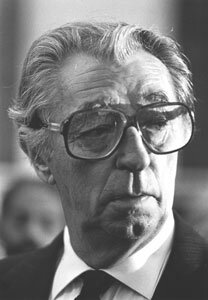

Organizers assigned a handler to make sure Robert Mitchum showed up at the gala and screening of Out of the Past at the 1993 Film Noir festival. Afterward, as he dragged on a cigarette on the Culbreth stage, he told the audience that the reason classic B movies were so dark was that the directors didn't have enough money to light them properly.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

Michael Moore was supposed to attend the 1995 festival for a screening of his comedy, Canadian Bacon, but his flight was canceled. He finally made it in 1997 for a screening of his film on corporate America, The Big One.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

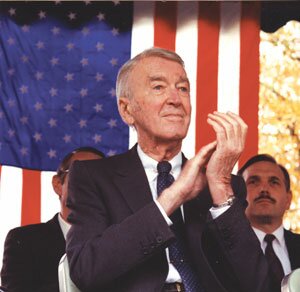

Gregory Peck discussed To Kill a Mockingbird at the second film fest in 1989. He shared top billing with Jimmy Stewart, but the two seemed to have little to say to each other, according to then-UVA president Bob O'Neil.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

Mr. Smith Goes to Charlottesville: It doesn't get more American than screen icon Jimmy Stewart, whose appearance set the bar high for star wattage at the second Virginia Festival of American Film.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

"The Reel South" was the theme of the 1992 festival, and Sidney Poitier, pictured with then-Governor Doug Wilder, introduced In the Heat of the Night.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

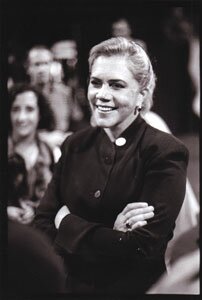

Serial Mom Kathleen Turner buzzed into town to introduce the John Waters film in 1996.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

Sigourney Weaver showed up at the 1999 TechnoVisions fest to pay tribute to creative genius Stan Winston at the opening night Aliens screening, and stuck around to discuss a non-Alien film, A Map of the World.

PHOTO COURTESY THE VIRGINIA FILM FESTIVAL

#

2 comments

I just read the above article and would like to make a correction concerning the comment by Mr O'Neil re my husband Gregory Peck and Jimmy Stewart "barely speaking to each other". This is absolutely wrong, my husband and Jimmy were very good friends, we used to get together regularly for dinner at their house and at our house Gloria, Jimmy, Greg and I.

Gregory and Jimmy held great mutual affection, respect and admiration for each other both personally and professionally, I

remember the evening of the Festival when both their films were shown, we were seating together in the theater and I still recall vividly how moved the four of us were, watching these powerful and memorable performances, we shared the very same feelings at this point in time and were deeply affected in a similar,unique, emotional and personal way.

It is most regretable that someone who was ignorant of the relationship and friendship between these two gentlemen would simply assume that because one was a republican and the other a democrat they would have" little to say to each other".

For the sake of accurate reporting and the memory of two fine Americans, I hope this letter will rectify the false assumption made in this article. If Mr O'Neil is still with us, I would welcome a personal answer from him.

Sincerely.

Veronique Peck

Mr Bob O'Neill can get in touch with me through the Virginia Film Festival and or the American Film Institute in Los Angeles CA

The classic film 12'Oclock High will always be my favorite.A superb performance by Mr.Peck was so well done it deserves more than a simple award.It ranks with the greatest for me and I'm sure many others.As a fellow Democrat I can only wish him the best.