Roger & Me: Seeing films through the master's eyes

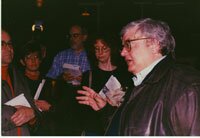

Ebert discusses Citizen Kane at the Jefferson Theater in 1992.

FILE PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

Filmmakers and film lovers are flooding into Charlottesville, and the Virginia Film Festival will again offer everything that has made it great, everything except one: Roger Ebert's "shot-by-shot" workshop.

I've attended all the Festivals. The first– then named the "Virginia Festival of American Film"– began on my birthday, in 1988. It was a dream come true. I became a Festival volunteer the following year.

In 1992, I jumped at a chance to work with Roger Ebert, who was coming to the Jefferson Theater to do an in-depth workshop on Orson Welles' Citizen Kane. To many, Ebert was just the "Thumbs Up" TV celebrity, but others recognized him as the Pulitzer award-winning author and indefatigable critic for the Chicago Sun-Times. I knew he loved movies like I did.

The first day, he entered the small lobby of the Jefferson where we volunteers held back the ticket holders until he could have a formal sound-check.

"This won't do" he said and led the crowd upstairs to the smaller cinema. An informal sound check was quickly done, and he talked to the crowd until it was time to start. The early birds got the witty anecdotes.

Ebert spent the first part of the three-day, six-hour seminar briefly discussing film composition and pointing out various things to look for. He explained that where the characters were standing in any given frame/picture often tipped who was in control at that moment.

"This is democracy in the dark," he said, explaining that once the laserdisc began spinning, any of the hundred or so attendees could speak up and we'd stop and discuss it.

"So," he said, "here we go."

Almost immediately, someone called out, "Stop!" The picture froze. "Mr. Ebert, I–"

Ebert corrected them quickly: "Roger!"

The person continued: "Roger– there's no one actually in the room when Kane utters his last word, ‘Rosebud.'"

The room erupted in laughter. A small continuity error? The whole movie revolves around reporters trying to find out what his dying word meant, and we collectively realized that one of the most famous opening scenes of all time was basically an impossible situation.

Over the next four years, Roger facilitated shot-by-shots for Sunset Boulevard, Vertigo, The Third Man, and Bonnie & Clyde. My duty from the second workshop on was to sit with him, armed with a flashlight to help with the remote in the dark theater. It was up to me to watch the time and keep the event moving. I'd get cheers when I corrected a problem with the disc and groans when Roger told the audience: "Carroll says we're out of time."

Minutes before each session, we'd meet and walk down the hall of the venue and discuss logistics. During one of these walks in 1993, I informed him of the death of 21-year-old actor River Phoenix the night before. He stopped suddenly.

"I interviewed him recently," he said. "He was a good kid." Our subsequent reunions began with his quip: "Who died now?"

Often, Festival attendees came to the first session of the three-day workshops, usually drawn by Ebert's fame. When they realized that our movie "watching" proceeded at a glacial pace, the crowd thinned.

That still left 200 or more to notice details they would have otherwise missed, or to see a film in a completely different light. If a question arose about what we had just seen, Roger would back up the scene and we'd watch it again. Not everybody could stomach spending six hours to watch a two-hour movie.

In Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo, Kim Novak's character walks into a dimly lit hotel room; she has had a complete makeover to please the obsessed character played by Jimmy Stewart. Roger pointed out that he felt it was one of the most erotic scenes ever filmed, one rumored to mirror Hitchcock's personal life. He discussed why he thought it was so powerful, then he said he'd run it again. A man in the audience asked if Roger would prefer us to all leave the room so Roger could have some privacy.

Roger replied coldly: "No– but you can leave." It brought the house down.

Ebert has spent a 40-plus-year career sharing his love for cinema. He has written thousands of movie reviews and six screenplays (although only Beyond the Valley of the Dolls made it to the screen).

He pointed out during Sunset Boulevard that a good movie is like an out-of-body experience. "You're not looking at your watch or thinking about what you're going to do after the movie," he said. "You're totally engrossed."

When I pointed out in an e-mail earlier this week how much he taught me, Roger replied, "What I hope you realize is how much I learned during those sessions."

In the spring of 1996, Ebert came to Charlottesville as a Kluge Fellow, covering Raging Bull. A year earlier, he taught from Pulp Fiction and introduced us to the term "MacGuffin." A small object that motivates characters and/or advances the story, the term is attributed to Hitchcock.

Watching Pulp Fiction, we noted the mysterious reappearing briefcase. When a character opened it– away from the audience view– it emitted a golden, glowing light that held the character spellbound.

"I know what it is!" called out a voice in the audience. "It's an egg MacGuffin!"

At the end of the roaring laughter that followed, Roger quipped, "That line is mine. From here on, I own that!" I believe it showed up in the Pulp Fiction DVD commentary.

Roger Ebert announced after the fifth Festival workshop that he had promised his wife he would cut back on festivals. He would return to Charlottesville every other year– three more times. We covered Blow Up, The Birds, and his last appearance was Chinatown in 2002.

In 2004, Roger was lured away by another film festival that wanted to present him a lifetime achievement award, and last year found him fighting complications of cancer of the salivary gland that had been troubling him for a few years. I would like to think that he'll rebound and may return to Charlottesville. One can only hope.

If I'm correct believing that the mission of Roger Ebert's career has been to help people enjoy the art of film, it is safe to say: mission accomplished.

Carroll Trainum can often be spotted behind the counter at BreadWorks, sometimes wearing his Boston Red Sox hat, which– along with his February 2004 essay on this page– has been credited with lifting the "Curse of the Bambino."

#