COVER- Where's the pork? The rise and fall of the Hogwaller name

PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

"Fifty-five dollars, 55, 55," the auctioneer barks, "54, 53, 52, 51– do I have 50?"

Pipe smoke occasionally drifts through the thick air, momentarily disguising the unmistakable odor of livestock. From the faded blue wooden bleachers and the sea of mostly middle-aged men, a single tan hand rises.

"51, 51, 52, 53"– the bidding slowly rises on a calf in a dusty pit, and the regular cadence of quick numbers is broken only by the occasional mooing of other cows waiting their turn. When bidding stalls at $64, the auctioneer's voice falls slient, and the calf heads to its destiny through a large door at the back.

This is how the Charlottesville Livestock Market has operated for more than 60 years, and this is the heart of Hogwaller.

Hogwaller: a remnant of Charlottesville history with a cloudy future.

In the face of the City's effort to distance itself from the name, only echoes remain. There's a band called the Hogwaller Ramblers, there's a home-grown beer called Hogwaller Kolsch, and there's a diner on West Main Street whose menu offers Hogwaller Hash.

It's a name that doesn't appear on any map, and it's one that some city officials wish would go away. And while for people who grew up there, Hogwaller has a special meaning, not all those memories are warm.

Sticks and stones

"I grew up there," said Gene Cassidy, who was raised at 811 Rives Street. "We had a nice, clean, neat home that we were proud of." But Cassidy, who died a year ago at the age of 74, felt the sting of snobbery on his daily walk to school. Along the way, he said, he and other students would hear jeers: "Here come the kids from Hogwaller!"

"It made you feel very small," Cassidy said. "It made you feel very self-conscious."

Cassidy explained that while white city kids could walk to the various downtown schools, his family– due to mid-century annexations in 1938 and 1963– had to travel two miles each way to Lane High School, today the County Office Building on McIntire Road. Hogwaller, he noted, "didn't even have sidewalks."

But pride and infrastructure aside, Cassidy said that one thing was sure: "The name really attracts attention."

Overton McGehee, the local director of Habitat for Humanity, has experienced first hand the kind of reaction the Hogwaller name can provoke. When Habitat bought Sunrise Trailer Court in the heart of Hogwaller several years ago, McGehee says, he was warned by people at City Hall to avoid the H-word.

"City officials told me not to use the name," he says. "They said, 'That's north Belmont.'" (It's actually located southeast of much of Belmont.)

City spokesman Ric Barrick says he can easily explain the warning: "It's more of a derogatory name that we would not endorse because it's classist," he says. "'Belmont' is the current terminology."

As far as history is concerned, Barrick says Hogwaller was never an official name: "It was a name that was used both positively and negatively by people, depending on what side of the tracks they were on. But it was never officially sanctioned."

Memories of a community

On the front porch of a house with white siding and brown trim, a man with a deeply lined face sits watching a cement truck rumble by. His rolled up jeans clash only slightly with an earring sparkling in his left ear.

"When I was growing up, you didn't see many cars," says Andy Lawson. "If you saw two cars all day long, you were a lucky damn man."

Lawson has lived his whole life between the sleepy streets of Rives and Nassau, in what he refers to as "the bottom," the lowest terrain of Hogwaller that backs up to the flood plain of nearby Moore's Creek. Born in 1939, Lawson is a member of an authentic Belmont industry bloodline: his grandmother worked at the nearby Woolen Mills, both his parents worked for the Frank Ix textile company on Elliott Avenue, and Lawson himself worked at Barnes Lumber adjacent to the Belmont Bridge.

One of seven children, Lawson grew up when Hogwaller was more country than city: he remembers when Franklin Street was nothing but gravel and tar, when the site of Rives Park was half cornfield/half cow pasture, and when the city limits had yet to totally cross the quiet neighborhood.

"It's hard to keep up with people nowadays," the retired construction worker says. "You don't know your neighbors anymore."

And he finds himself faced with other modern problems; his family says street racing occurs regularly on their block, and they suspect drugs and violence are present in their once-placid community.

Lawson bought his current house at 914 Nassau Street just across from what is now Rives Park for $4,000 in 1969. Today the ritzy Linden Town Lofts condominiums– starting price $249,000– are just a stone's throw away, and his parcel now has an assessed value of $120,000.

"This little house has withstood a lot," Lawson smiles. He has raised four kids, two sisters, and a grandchild there.

Over the years there's been lots of positive change, but Lawson says destruction has also taken its toll. Though he says he's pleased with improvements in infrastructure and new opportunities for kids in the neighborhood, he's outraged over the recent removal of the Woolen Mills dam. "It should have been history," he says, his voice rising in anger. "It ain't no different than Jefferson's place."

And though he's proud of where he's from, Lawson sees more value in people than in places. "It don't make no difference where you live," he says. "It matters what you want to be. Life is what you make it."

Keeping the 'hog' in 'Hogwaller'

It's the first Saturday afternoon in September, time for the weekly auction at the Charlottesville Livestock Market. Old advertisements for farm equipment and Chevy trucks cover one wall of the dilapidated, but still very much operational, arena.

In the dusty pen below the bleachers, a man in a pristine white cowboy hat, sporting a mustache, a massive belt buckle, and mud-encrusted work boots, leans on a long green stick, occasionally wielding it to prod a white calf with black ears, nose, and feet.

"324-pound bull calf," the auctioneer calls out.

On a walled platform just above stand two men, one with a microphone and one with pen and paper. A small wreath of flowers hangs just above a sign, "Auctioneering by Dick Whorley."

The Charlottesville Livestock Market sits at the bottom of the steep hill cradling the neighborhood between I-64 and Belmont, overlooked by a sea of single-story concrete bungalows from the 1940s and '50s, many with verdant views of Monticello Mountain. Closely packed trailers line a lot across the street.

The livestock market got its start on Garrett Street in the 1800s before moving just southeast of Douglas Avenue, along the bustling C&O rail yard the City converted to an office park in the late 1980s. It moved to its current site at 801 Franklin Street in 1946.

Owned by John H. Falls since 1980, the Charlottesville Livestock Market still holds auctions every Saturday, and at least once every five years or so, an animal escapes. But cows and pigs aren't the only things that have played in the Hogwaller mud.

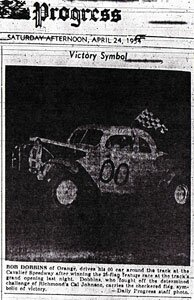

A vacant field between the Livestock Market and the creek was home for a while to Charlottesville's first and last stock-car track, owned and operated by George Durham. Cavalier Speedway was a quarter-mile dirt oval track that seated about 3,500. It opened on an overcast April evening in 1954, when Orange County's Bob Dobbins won the 25-lap race, cheered on by a full house.

One of many tracks appearing across the South at the time, the venue also featured wrestling matches, turkey shoots, and daredevils. But the Speedway's glory was short-lived, and it closed after just two years. Today, the site remains an empty field.

Origins of a name

Tucked between urban downtown and the base of Monticello Mountain, Hogwaller is situated down Carlton Avenue on the lower side of the hill on which upper Belmont stands, thus its occasional reference as "Lower Belmont" or "Carlton."

The neighborhood melts into Belmont at Monticello Road, a main drag until it was bypassed in the early 20th century by Monticello Avenue, a speedier route connecting the city to the third president's mansion and open land to the south.

Moore's Creek encircles the southern and eastern borders of Hogwaller, winding its way to the Rivanna River in the East, just past the Moore's Creek sewage treatment plant.

Many Charlottesvillians believe Hogwaller owes its name to the location of the livestock market, a low-lying region where rain occasionally causes flood waters to creep up and create a muddy mess in the market stockyards where the pigs could wallow.

Andy Lawson says the name preceded the livestock market, but emerged from the same site. His account is seconded by a former neighbor who says that a man named Dixon penned a large number of pigs in The Bottom.

Belmont residents just up the hill called it "Hogwallow," which comes out as "Hogwaller" in southern drawl. Some feistier Hogwallerans are rumored to have said they'd rather wallow with pigs than be caught up in the urban rat race, leading them to refer to upper Belmont as "Rat Run." But if "Rat Run" never caught on, Hogwaller stuck for a long time, and, packaged with many mixed emotions, is still heard today.

As original as the moniker may appear, "Hogwallow" may have existed before the neighborhood.

On April 13, 1915, the Daily Progress began running a syndicated column by a fictional correspondent named Dunk Botts. A southern version of A Prairie Home Companion or The Onion, "The Hogwallow News" parodied a stereotypical rural southern town.

"A roach crawled into Poke Eazley's right ear Monday night when he was not listening, and its arrival out the left ear is looked forward to with much anxiety by Poke," reads one of the first columns. "Columbus Allsop is on trade for two more dawgs," jokes another, "to take up surplus fleas at his house this summer."

The humor column was unceremoniously yanked on May 1, 1917, a few weeks after America's none-to-humorous entrance into World War I. Yet it soon became apparent that Hogwallow was the new official name of the stereotypical Southern small town.

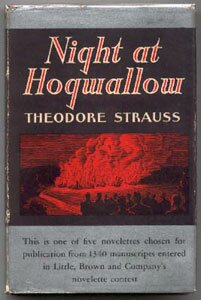

When publisher Little Brown and Co. held a novelette contest in 1937, one of the five winners was Night at Hogwallow by Theodore Strauss, a tale of violence and racial tension in a Southern community. And in the late 1940s, following the popularity of Al Capp's hillbilly comic Li'l Abner, a new comic called Hickory appeared, set in a fictional Southern town called– you guessed it– Hogwallow.

'The best of two worlds'

Monticello Road may be a metaphor for the two faces of Belmont. At its northern end, a short walk from the Downtown Mall, it's home to two upscale restaurants: Mas and La Taza. At the road's southern end, in the heart of Hogwaller, stands Moore's Creek Restaurant (which recently changed its name to County Line) whose menu offers breakfast all day, including scrapple.

To many, it's this kind of color that proves Hogwaller still exists despite being almost engulfed by the ever-expanding gentrification of Belmont, which traces its origins to a plantation of that name whose manor house still stands.

Anyone ambling down Monticello Road or any of the other steep streets of southeast Belmont can see the scene shift from substantial two-story brick and frame houses to smaller bungalows, primarily built of unadorned concrete block. Expensive landscaping gives way to small lots crowded with plastic yard animals and old Christmas decorations. And anyone pausing to sniff the odoriferous musk wafting from the Livestock Market might just hear the distant grind of shifting gears or maybe even the faint clip-clop of hooves, each an echo of Hogwaller history.

Looking out the window with a wistful smile on his face, John J. "Skip" Tornatore III reminisces about his life. He moved to the Woolen Mills area in 1950 when he was 10 years old. His father opened Helen and John's Grocery in 1957, at what was then 24 Franklin Street (now #131), just past the railroad underpass up the street from the stockyards.

"It was a country atmosphere with city conveniences," he says. "We had the best of two worlds."

Tornatore remembers a different time when nothing but a dirt road ran past the store and its hitching post out front. Like Lawson, he recalls a close-knit community where families on the street knew each other and kids swam and fished at Woolen Mills. He says shoppers at his store would pick up groceries during the week and come back on the weekends to pay.

"Everybody knew everybody," he says. "It was more friendly."

Although Tornatore recalls Hogwaller kids catching a hard time from city children for being "country," he also remembers friendly football and baseball games at area parks between kids from different neighborhoods, and everybody sitting up on a hill to watch the races at the Cavalier Speedway.

"We cared about people, respected people," Tornatore says. "You knew not to do wrong because the news would get home before you did."

Helen and John's Grocery served the Belmont community for 44 years. John's father and mother ran the store until the 1970s when Helen Tornatore died and John Tornatore II retired a few years later. "Skip" eventually took over and ran the store for 23 years into the '90s, when he retired for health reasons and the store was closed.

Today, at 66, Tornatore is a part-time greeter at Sam's Club living in a pleasant house across town near Jefferson Park Avenue, and the old store is now the site of a storage business.

"I loved the neighborhood," he says. "Now it has really changed."

Tornatore says what bothers him most is that many of the older residents have moved away. "The houses have gotten more expensive," he says. "It was blue-collar workers back then."

But more than any material or sentimental loss, Tornatore says he misses the community. "People always ask me, 'Do you miss the store?'" he says. He always answers the same way: "I miss the people."

One person with whom he's still close is Bob Shaw, 66, a long-time friend who spent a lot of time visiting Tornatore as a child.

"It was an average area, just a nice little section of town," Shaw recalls. "People who lived there were just regular, middle-class people, proud of the name Hogwaller."

Shaw says he can only speculate why the name has become unpopular. "I guess people wanted the city to have a good name," he says, "to be a world-class city."

And though outsiders may not use it anymore, Shaw says he doesn't think the name is going anywhere. "The people there still call it Hogwaller," he says. "That's their identity."

'What's in a name?'

Dan Lefkowitz understands why a simple name could become an object of such contention. The professor of linguistic anthropology at UVA says that while he has no specific knowledge of Hogwaller, he can attest to the power of names.

"Words can have deep resonance with people," he says. "There's often encoded historical and cultural knowledge in place names."

Lefkowitz also says awareness of the stories behind the words has historically caused some names and phrases to fall out of use. That would certainly include the downtown neighborhood that's now the site of Friendship Court, which many an elder white Charlottesvillians used to call, well, n-town, only they didn't always abbreviate.

"In the '60s and '70s, there was a purging of potentially offensive language," he says. "Once the word has that certain meaning, it continues to propagate the original negativity associated with it."

But the use of a name can be more complicated than just good or bad. "When these names come into the public domain, there are different rules," he says. "The person who uses the word matters. A place name might represent a pride in locality for those who live there but be taboo for outsiders."

With the complexity of words, Lefkowitz says nothing can be interpreted at face value alone. "As linguists like to say: 'There's no cat in catalogue.'"

But former store owner Tornatore doesn't see any deep meaning or prejudice in Hogwaller. "What's in a name?" he says. "A name is just a name."

"It don't bother me none," says stockyard owner John Falls.

"It don't make no difference what they call it," agrees life-time resident Lawson. "It's where I've lived all my life. It'll still be Hogwaller no matter what."

And so, meaningful or not, while the Hogwaller name has fallen out of common use for the neighborhood, it hasn't disappeared entirely. It still regularly circulates in conversations about local music.

'Too good a name to waste'

It's Sunday, September 2, a day after the auction. Two miles away at Fellini's restaurant downtown, the windows are thrown open, the lights turned low and the music turned up, and every seat in the house is filled for a final Sunday-night show by the Hogwaller Ramblers. From the band packed tightly in their regular corner just inches from the bar, the old time toe-tapping bluegrass/rock strumming and breakneck tempos please a cheering crowd.

The Ramblers have been a staple of the Charlottesville music scene for 16 years, and likewise, front man Jamie Dyer has been a fixture in lower Belmont for decades. He says he's been "couch surfing" in Hogwaller for 25 years.

Unhappy that the name is falling out of the Charlottesville vernacular, the adamantly proud-to-be-country Dyer says he loves the name's rural, gritty, and slightly "in-your-face" qualities, and he speculates these are the reasons it has become politically incorrect.

"They should call it Hollywaller if they want it to be upscale," says Dyer. "People are afraid of Charlottesville being thought of as a cow town."

Dyer, now sitting at a corner table in the Blue Moon Diner, a place where everyone knows his name and where the menu offers a dish call Hogwaller Hash, says he settled on the band's moniker after weeks of searching.

"I took the name because I was trying to evoke the Southernness and localness of it," he says. "No one was using it, and people seemed to hate it, so it was the perfect name.

"It was a metaphor for what happened between the classes in America," he says, describing how Hogwaller is torn between city and country, with I-64 blocking it from Monticello mountain, and gentrified downtown encroaching from the northwest.

"It's like if New York City told people not to use the name Hell's Kitchen," he says. "It's a small piece of our heritage. It bums me out that people are willing to let go of that kind of stuff.

"Besides," Dyer grins, "it's too good a name to waste."

Dollar signs of the times

Thanks to the tightly packed neighborhoods to the north and west, and restrictions on building in the flood plain to the south and east, there's limited space for development in the neighborhood. But with its accessible location and mountain views, the area has long been ripe for gentrification.

The well-documented explosion in Belmont property values has begun to make its way down the hill– but not without resistance. In recent years, the local chapter of the high-profile non-profit organization Habitat for Humanity, which aims to build quality housing for those who can't afford it, has been fighting to stem the tide of gentrification in both the city and county.

Sunrise Trailer Court, a trailer park built on an old hay field between Franklin Street and Carlton Avenue in 1955, is a member of an increasingly exclusive club: affordable housing within Charlottesville's city limits.

Habitat for Humanity bought the 2.3-acre parcel in November 2005 for $1.2 million in an attempt to preserve affordable housing and offer "a vibrant, attractive urban neighborhood" to current residents.

But Sunrise is only one chunk of land, and the first signs of gentrification have already begun to spring up around it. Aptly listed under the header "Condo-Mania in Charlottesville" on one realtor's site, Linden Town Lofts is a three-story Gargantua of modern upscale condominiums, complete with private gardens and rooftop terraces. Just blocks from the livestock market and the trailer park, these swanky pads can go for as much as $300,000.

Falls says development and construction have displaced some nearby farmers, but he doesn't see his livelihood going anywhere. "It's been all right," he says of business at the livestock market, "same thing as always down there."

"Skip" Tornatore has long since moved out of greater Belmont, but he's still frustrated by what happens to the old-timers when development moves in. "The thing that bothers me," he laments, "is the older you get, the more things are going to cost you. These older people can't keep up with taxes and times."

Andy Lawson voices the same concerns. Today, his property taxes rival what he paid for the house in the first place. "You work for inflation now," he says.

Though some things have remained constant in Hogwaller– the hilly streets, the smells of the stockyards, the intersection of country and city– Tornatore says something has been lost. "It is a different world," he says. "It just shows that times change."

Lawson says he has always found a way to deal with new people, new development, and new problems. "I never would have thought those things could happen," he says, "but life grows. It's just like people. That's life."

And despite the changes, life in Hogwaller also goes on.

"The Hogwallow News" column appeared in the Daily Progress from April 1915 to May 1917.

ARCHIVE IMAGE

Andy Lawson was born and raised in Hogwaller and still lives there today.

PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

Orange County's Bob Dobbins won the opening race at the Cavalier Speedway on Friday, April 23, 1954, and made the front page of the Progress the next day.

ARCHIVE IMAGE

John "Skip" Tornatore's family ran Helen and John's Grocery down the street from the stockyards for 44 years.

PHOTO BY ADAM SORENSEN

This tale of violence and racial tension in a Southern community was published in 1937.

PHOTO BY ADAM SORENSEN

Carter's Mountain looms over the Rives Street Market.

PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

Musician Jamie Dyer fronts a long-running band called the Hogwaller Ramblers.

PHOTO BY TOM DALY

The place that some think gave Hogwaller its name: the Charlottesville Livestock Market.

PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

Along with Quarry Park (not shown), Rives Park provides Hogwallerians with a place to play.

PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

Although it's said to be renamed "County Line Restaurant," the only full-service restaurant in Hogwaller still proudly wears the Moore's Creek name.

PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

How many multi-Starbucks towns also have sheep for sale inside the city limits?

PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

Habitat for Humanity has bought Sunrise Trailer Court with plans for an upgrade.

PHOTO BY WILLIAM WALKER

#