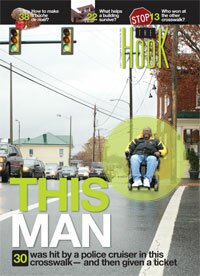

This man: was hit by a police cruiser in this crosswalk-- then given a ticket

Gerry Mitchell was hit, then ticketed.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Heading home from a trip to Reid's supermarket on Preston Avenue about a month ago, Charlottesville artist Gerry Mitchell stopped his motorized wheelchair on the sidewalk along West Main Street and waited to cross.

Even though the powerful drugs he takes to control AIDS have weakened his bones so badly that he can no longer walk, his failing health was not on his mind that morning. "I was just happy," he says.

As the light in front of him turned green, Mitchell rolled forward into the crosswalk. Moments later, a powerful jolt from behind threw him from his chair and tossed him face down in the street.

Stunned from the blow, Mitchell looked up to see an Albemarle County police officer leaning over him, asking if he was okay. But as Mitchell would soon learn, the officer wasn't part of the rescue team; he was the driver of the vehicle that had just struck Mitchell's wheelchair from behind.

And then, several hours later, in the University of Virginia Medical Center emergency room, Mitchell got another jolt.

"You're not going to like this," Mitchell quotes the officer who paid the call. It wasn't flowers or well wishes the officer came bearing. It was a traffic ticket.

Not what he needed

Gerry Mitchell's life has not been easy. Although he studied art at Yale University and has operated galleries in San Francisco and Barcelona, he found himself on the cutting edge not only of art but also medical history.

In 1981, Mitchell discovered that he was infected with a then little-known but lethal virius, HIV. After watching scores of his friends die from the disease, in the mid-'90s he, too, developed full-blown AIDS. He's one of the world's longest survivors of the deadly disease.

"It's a miracle I'm alive," says Mitchell, a Charlottesville native who says his brother moved back to their hometown five years ago to help him after doctors had given Mitchell months to live.

Mitchell, now 53, says he never let the illness or doctors' warnings slow him down. Even now, wheelchair-bound and with his dexterity diminished from several strokes, he paints daily and donates all the proceeds from his frequent shows to charity– $100,000 in the last several years, by his account.

"He's an amazing guy," says John Lawrence, owner of the Mudhouse coffee shop on the Downtown Mall, where Mitchell has shown his work twice in the past and will again in January. "I've never met anyone with such a positive mental attitude and such a joy for life."

The accident, Mitchell says, dampened some of that joy.

Mitchell was treated and released the day of the accident, but by the following day he was back in the hospital suffering from renal failure, something he says his doctors attribute to the blunt blow to his back.

"I didn't need this," he says, "on top of everything else."

Excessive force?

What happens between officers and ordinary citizens in crosswalks has lately been a subject of local controversy. In the early morning hours of September 29, just four blocks east of Mitchell's accident, two young adults allege that they were almost run over by a Charlottesville police officer.

According to recent trial testimony, an Iraq war veteran and his fiancée, Richard Silva and Blair Austin, were walking across Water Street toward the parking deck after a birthday dinner on the Downtown Mall when Officer Mike Flaherty came speeding down Second Street on his way to a call.

After Silva threw up his hands and uttered some variation of "Slow your a**" or "Slow the f*** down," Flaherty hopped out of his Jeep to arrest him. When Austin asked why, Flaherty pushed her, and her tumble onto the pavement prompted at least one bystander to call 911 to report the officer's behavior.

Flaherty charged the couple with being drunk in public and Austin with obstruction, and the two filed a formal complaint against Flaherty. After a five-hour trial on November 29, Silva and Austin were found not guilty of all charges.

Flaherty testified he ended his response to the original call for back-up in order to deal with Silva, whom Flaherty believed posed a safety hazard. Silva, he said, was "bobbing and weaving" and had "puffed out his chest."

In court, Charlottesville District Court Judge Bob Downer stopped far short of reprimanding Flaherty. Instead, he seemed to suggest he believed Flaherty's account– that Silva refused to leave the middle of the road and that Austin interfered with the arrest. The judge said that prosecutors simply hadn't proven their case "beyond a reasonable doubt."

The internal police investigation into that matter remains open.

Slow motion

Gerry Mitchell's accident occurred Monday, November 5, the kind of fall day that could make even a dying man smile– cool and crisp with temperatures in the mid 50s, glowing foliage under a clear blue sky.

As he waited around 10am at the intersection of Main and Fourth across from Main Street Market, the groceries he'd just purchased from Reid's hanging from the back of his wheelchair, he imagined the bowl of beef stew he planned to make for lunch and an afternoon he hoped to spend finishing a painting for an upcoming exhibition. His plans were about to be interrupted.

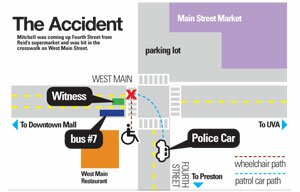

For one west-bound driver, the incident unfolded like a nightmare. Ben Gathright, 25, saw Mitchell waiting to cross, and when the light in front of his car turned yellow, rather than rushing through, he stopped and motioned to Mitchell to cross.

As Mitchell set off in his wheelchair, the police cruiser that had been idling on Fourth Street began turning left onto West Main– Gathright watching in horror.

"I was thinking, 'Oh my God, he's going to hit him!'" says Gathright, adding that he could do nothing to stop the collision. On impact, Mitchell "was pitched a good five feet from his wheelchair," says Gathright, who left his car running and rushed to offer aid– as did the officer who struck Mitchell.

A man aboard a Route 7 Charlottesville Transit bus, stopped at the light on its way to Fashion Square Mall, was also stunned to see the police cruiser hit a man in a wheelchair.

"I don't understand how he didn't see the guy," says passenger Haywood Johnson.

'Blind spot'

Gathright and Mitchell say the officer's initial reaction was apologetic. "He said he had been 'looking down' as he turned," says Gathright. But they claim that once Mitchell was on the side of the road and police back-up had arrived, the sense of contrition had evaporated.

"Suddenly, they said I was in his blind spot," says Mitchell. "I said, 'You've got to be kidding. He almost killed me.'"

Gathright says he couldn't understand why police never took a formal statement from him, although he remained at the scene and told them he had witnessed the entire event.

Gathright says Mitchell was shaking, crying, and worried about the fate of his $13,000 motorized wheelchair, which would not fit into an ambulance. Gathright wanted to call an ambulance anyway, but he contends the officer did not.

"I said anything could happen," says Gathright. "He could be bleeding internally, you call the ambulance."

Gathright says he pointed out that Mitchell had mentioned having a stroke just a week earlier. The officer's response, according to Gathright: "The law says if he doesn't want medical care, he doesn't have to have it."

The officer, Gregory Charles Davis, did not return the Hook's call for comment, and Albemarle County police spokesperson Lieutenant John Teixeira says the department will not comment on the matter.

Eventually, Mitchell, realizing he was bleeding from wounds to his legs and arms, relented and agreed to be taken to the University of Virginia Medical Center.

Several hours later, as he was being examined in the ER, Mitchell says, Charlottesville officer Steve Grissom showed up with a ticket. But it wasn't a photocopy of a ticket issued to the officer who struck him: it was a ticket for Mitchell. There was no ticket issued to the officer.

"He said, 'You didn't push the button,'" Mitchell recalls. "We have video of you."

That video, allegedly shot from a camera mounted at the front of Officer Davis' cruiser, purportedly shows a "don't walk" signal that Mitchell may have violated.

"That's when I got angry," says Mitchell.

Whatever else the video may show– such as the force of the impact or Davis' actions in the collision's aftermath– may take a while to discover. Teixeira, citing an ongoing investigation, has denied the Hook's request for a copy.

Internal investigations

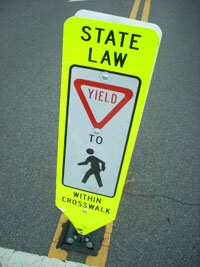

In recent years, the City of Charlottesville has taken several steps to create a more pedestrian-friendly city. In 2006, the city erected a series of signs in the middle of non-signaled downtown crosswalks reminding drivers of their obligation to yield to pedestrians.

Pedestrian activist Kevin Cox says those signs– particularly noticeable at the crosswalks near the Downtown Mall– have helped increase driver awareness of pedestrians, and he has noticed drivers have been "more courteous" at those intersections since the signs went up.

John Wetmore, the Maryland-based founder of the website pedestrian.org, and creator of the nationally distributed public access TV series Perils for Pedestrians, says in cases like Mitchell's, the driver should be ticketed.

"If you're a turning vehicle, you have an obligation not to run someone over," he says. "It's not like you're going down the road and someone jumps out in front of you." (Wetmore's show airs locally on Comcast channel 13 at 7pm on Mondays.)

Wetmore says that common-sense physics explain why. "When you're turning, you're starting from close to zero miles an hour," he says. "You wouldn't have any trouble stopping if you looked."

So why was Mitchell charged, while the driver who struck him was not? With police officials in both Charlottesville and Albemarle refusing to answer any questions, that's hard to determine. But one veteran attorney believes she understands.

"I can only think of one reason," says attorney Debbie Wyatt. "It's really for liability purposes."

City spokesperson Ric Barrick says no one in the city or on the police force will comment. We "don't want to get in the habit of playing these events out in the press," he says. "We feel the debate should remain in the courts and not in the public."

Could this really be an example of "the best defense is a good offense"– or perhaps of the "thin blue line," the supposed protection brothers of the badge provide each other?

"It's certainly been a tried and true method, and it's certainly been a practice I've seen in the county," says Wyatt, who recently won a $4.5 million civil judgment against the county after an officer shot and killed an allegedly berzerking man in a Rio Road apartment 10 years ago. Wyatt notes that five officers in that incident reported themselves as injured.

"Jaywalking isn't generally prosecuted in this town," says Wyatt. "I think this is an abuse of power."

The law, however, can be complicated. One part of Virginia code says that pedestrians in a crosswalk have the right of way– particularly when they're facing a green light. But Mitchell was also facing a "don't walk" sign.

"It's chaotic," says pedestrian advocate Cox, citing Charlottesville's smorgasbord of intersections. Some have buttons a pedestrian must press to prompt the walk signal; other intersections offer no buttons, with pedestrian signals simply coordinated with the traffic signals. Sometimes there are no pedestrian signals at all.

"It should be standardized," says Wetmore. "If you have to push the button to get a walk signal, there should be a sign that says, 'You must push button for signal,' Otherwise, you don't even know you need to look for it."

In Virginia, this confusion has been recognized by the agency with the power to do something.

"We're looking at changing the Code because of these types of problems," says Jacob Helmboldt, state bicycle and pedestrian program coordinator for the Virginia Department of Transportation.

"It makes no sense that the police would ticket him for that," says Helmboldt. "Pedestrians have the reasonable expectation to think that when the light is green they can cross with traffic."

But in light of Barrick's comments, if Mitchell wants answers about why he was ticketed and the officer was not, his only recourse is to file a complaint with the Charlottesville police department and request an internal investigation. That, some say, is a problem.

"I don't believe a department should investigate itself," says Lloyd Wood, who sits on the Citizen's Advisory Committee of the Albemarle County Police Department. Established in 2002 at the urging of a County man who'd been ejected from a Western Albemarle High School football game for smoking a cigar, it's one of many such groups that municipalities have established to create an unbiased and nonthreatening forum where citizens can take complaints about police behavior. Although the Albemarle County committee has no direct power over police personnel, it can make recommendations to the Albemarle Board of Supervisors. In addition, Wood says, Albemarle police often ask State Police to conduct investigations into controversial matters.

"That way," he says, "there's no question about anyone doing anything wrong."

Dana Slater, an attorney and herself a former Albemarle County police officer– who is also a member of the Committee– says such committees are no cure-all, in part because many citizens don't know they exist.

Even when people do know about it, Slater says, they often they shy away from complaining, and Wood notes that only one member of the public has ever lodged a complaint in the six years of the committee's existence.

Will Charlottesville ever establish such a board? Is it needed? In 2005, Chief Longo showed his willingness to request an independent investigation into officers' conduct when he asked both the state police and the FBI to investigate two officers.

Longo had suspended Charlottesville Police Officers Roy Fitzgerald and Charles Saunders in 2001 following a complaint that they attended a stripper party while on duty and in uniform, but it was a series of other allegations about corruption and bribery that eventually led him to ask for outside help– and win praise from U.S. Attorney John Brownlee.

"His proactive approach demonstrates the bravery and integrity of the Charlottesville Police Department," said Brownlee of Longo in a 2006 press release. Saunders and Fitzgerald, who were fired from the department in 2005, eventually pled guilty to lying to a federal agent, and both served three months in prison.

"Apalled"

After he was treated at UVA Hospital, says Mitchell, and a Charlottesville police officer's offer of a ride fell through, he caught a cab back to the Main Street Market. His wheelchair, although bent, was still operable, and a samaritan had bundled up his groceries and hung them from the back of his chair. He wheeled back to his downtown home at a senior citizens high-rise.

It was witness Gathright who brought Mitchell's accident to the Hook's attention. He says he was outraged when he saw the accident, and his outrage grew when he found out later that Mitchell was the person ticketed.

"I can't express how appalled I am," says Gathright. "To me this is just insane. What if it were a civilian driver?"

Attorney Slater, declining comment on this specific case, says the law typically allows both parties to be charged in one incident. She says she often did just that when she was an officer in cases where there was probable cause to suggest both sides had some blame. "Let the court sort it out," she says.

The sorting out begins for Mitchell at 9am December 6. That's when he must appear in Charlottesville District Court to defend himself against the charge of "failure to obey a pedestrian signal."

Like Wyatt and many of his friends, Mitchell believes the ticket was simply an attempt by the police to limit their liability if he decides to sue, something he says he's considering. If he does, he may have difficulty winning a judgment, particularly if he's found guilty. That's because Virginia is a "contributory negligence state," says Slater, meaning if a victim can be shown to be even one percent liable, he cannot collect anything. (Most states follow the doctrine of "comparitive negligence," which allows judgments and awards even when blame is shared.)

Whether he sues, Mitchell says he wants an apology– and a guarantee.

"I was treated like a dog," he says. "I don't want this to ever happen to anyone else again."

The day after he was hit by a police cruiser, Gerry Mitchell was hospitalized for renal failure.

PHOTO BY COURTENEY STUART

At the crosswalk at West Main and Fourth Streets, the pedestrian signal shows "don't walk" with the green light unless a button is pushed.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"Doctors call me the miracle man," says Gerry Mitchell, who has been HIV positive since 1981, and who suffers from side effects of drugs he takes to control his illness.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Mitchell was coming up Fourth Street from Reid's Supermarket and was hit in the crosswalk on West Main Street.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

In 2006, the city erected bold signs like this one in crosswalks around downtown.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#