NEWS- Wheeler dealer: Pleading for parking lot divestment

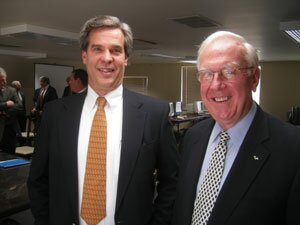

CPC manager Bob Stroh and chairman Jim Berry.

PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

Why is UVA President John Casteen getting certified letters containing pop culture references from the 1980s? It's all part of the fireworks over Charlottesville Parking Center, the little-understood company that's been subsidizing downtown parking for nearly 50 years.

When the Hook last reported on Charlottesville Parking Center Inc. in March, it was the eve of the CPC's annual meeting, and chair Jim Berry had just announced that the company and/or its assets would be put up for sale ["Grand design: Does CPC breakup mean windfall?" March 22]. Eight months later, the company has yet to release an info pack or hire a broker to list the company for sale. So a self-described "rebel shareholder" has taken matters into his own hands.

"It's time to profit," said the shareholder, Spencer Connerat, in a recent email discussing his desire that banking giant Wachovia, which already owns about nine percent of CPC, buy up the rest of the company. Besides benefiting CPC shareholders, such a deal would give Wachovia a toe-hold in the burgeoning Charlottesville real estate market.

In recent weeks, the Florida-based Connerat has been peppering the board and management of CPC with literally dozens of emails alleging that CPC brass are dragging their heels in order to push a sweetheart deal with the City of Charlottesville.

Now, why would he think a thing like that?

For starters, the City recently spent $128,000 to conduct an international architectural design contest for a two-block area of primo real estate whose largest owner isn't the City but the CPC.

Connerat says he and the other "long-suffering" stockholders should be free to sell their assets on the open market. So in October, he formally asked Wachovia to consider a CPC takeover. Specifically, he wants Wachovia to engage in a 1:1 stock swap that would value shares of CPC at nearly $43 each. That's quite a premium for shares that were issued for just $1 each.

CPC was founded in 1959 when Barracks Road Shopping Center was opening and– with its vast acres of free parking– threatening to dampen downtown sales. Worried downtown merchants reached out to one another in what may have seemed a charity plea.

CPC, however, was no charity; it just acted like one.

CPC was incorporated as a standard corporation, but it offered comparatively generous parking programs that allowed downtown businesses to give away parking for two hours without requiring a purchase. (A mile west in the Corner district, parking is doled out in half-hour increments.)

Many of today's CPC shareholders got their stock from companies that were pressured to invest to stave off the threat posed by Barracks Road. In a roundabout way, that's how Carol Troxell ended up with hers.

At the annual meeting in March, Troxell revealed that her stock in CPC came with her purchase of New Dominion Bookshop. Another shareholder in attendance that day, 84-year-old W.P. Moore, said he got his stock in a coin toss when he was liquidating a brokerage (originally called Auchincloss, Parker & Redpath) back in the 1960s.

Ironically, neither of today's two biggest shareholders were among those early downtown-saving businesses. Like Connerat, their acquisitions began after the effort to save downtown.

In its 49-year history, Charlottesville Parking Center Inc. has never paid its shareholders a dividend, but that doesn't mean they haven't gotten rich. At the time of last year's annual meeting, the two largest investors– Jim Berry and the estate of Hovey Dabney– had accumulated 36 percent of the company, 183,245 shares between them. A Wachovia buyout would provide a payout of nearly $8 million. And for Connerat, that's part of the rub.

He alleges that in the 1990s Berry and Dabney were telling shareholders that their stock was nearly worthless and offering to buy it up for no more than $1.05 per share. Dabney, a Charlottesville business icon and war hero, died last year, and Berry isn't returning a reporter's phone calls.

A 2003 letter from CPC to a shareholder suggested that nobody but CPC itself was interested in buying shares and offered to pay $1.15 for each one.

Local developer Richard Spurzem has made a career out of looking for hidden value. After being rebuffed by CPC in his quest for a shareholder list in 2003, he took matters into his own hands and placed an ad in a newspaper expressing his interest in buying shares. He found some takers.

"It's just a small privately held company," explains Spurzem. "It's up to the board of directors to decide what to do." But to Connerat, the board has been a source of great frustration.

In October 1996, Connerat was a fledgling stockbroker associated with what was called Jefferson National Bank, then run by Dabney and Berry, who also ran CPC. He says he watched with fascination as they bought up CPC stock– splitting shares between them equally.

One day, Connerat arranged– he says he had Berry's verbal permission– to purchase some CPC shares from the estate of a bank customer. His employment was promptly terminated. While he acknowledges that the purchase was a technical violation of securities rules (because it wasn't tendered in writing), he actually blames his firing on Berry's second thoughts.

"It's called greed," says Connerat. "It's called jealousy. He told me, 'Hovey and I are on the hot seat here.' Who was this 28-year-old kid getting into their game?"

Since then, Connerat has tried to open up the sometimes secretive world of CPC. Not long after his firing, for instance, he found that CPC hadn't been following all the proper corporate procedures, and in 1997 he won a legal action against the company (a writ of mandamus) that actually landed him– for one term anyway– on the board.

Now, concerned that a "sweetheart deal" with the City could be in the works, Connerat is asking why a company that's ostensibly for sale has not yet released a prospectus (an info packet) for potential buyers.

"You may work for yourself, but you work for me too," Connerat told CPC head Berry in a recent email lambasting what he sees as undue secrecy and alleged mistreatment of shareholders. In recent days, Connerat's persistent communiques have become more strident, filled with pop culture references such as, "Do you really want to hurt me? Do you really want to make me cry?"

But how likely is it that septuagenarian Berry will catch the reference to gender-bending 1980s musical icon Boy George? And will Casteen, busy running a $3 billion capital campaign as president of the University of Virginia, take any pleasure in Connerat's cc'd letter describing a Wachovia buyout as "as easy as a Tim Duncan lay-up over John Crotty"?

"He sits on the Wachovia board," says Connerat of Casteen. "I want the board to be aware of the situation."

Wachovia's annual meeting is coming up April 22. Already, Connerat contends that Wachovia's corporate lawyer has told him he doesn't hold enough shares to propel his proposal into the proxy statement, the all-important annual mailing to shareholders.

"I don't think I said it won't appear," says Wachovia corporate counsel Anthony Augliera. "There's a process, and we follow it." He said it was too early to say whether the proxy statement, slated for release in March, would contain the proposal.

If Connerat gets his way and Wachovia does orchestrate a take-over, one result could be the ouster of the current company board, an action that might imperil not only the cheap and easy parking that downtowners have come to expect, but could also derail City Council's desire to sculpt a new face for Water Street.

Blasting the existing CPC board as "do nothing," Connerat says new ownership could breathe life into CPC whose key assets are the land under the Water Street Parking Deck, 284 spaces in that deck, and the one-acre, 126-space asphalt parking lot next door.

Connerat's efforts have snagged the attention of CPC's corporate lawyer, Bob Hodous.

"The corporation will not be making a sweatheart deal with the City of Charlottesville," Hodous insists in a recent email. "However, given that the City is the largest owner of units in the Water Street Parking Garage Condominium, and given some of the provisions of the contracts involved with the underlying property and that condominium, the City has a unique interest which in fact may bring a higher price than might be obtained from others."

The asphalt lot alone was nearly sold last year for $8 million, but, sources say, the would-be private buyer let his monthly $40,000 option payments expire when the real estate market softened.

At the last annual meeting, which the Hook attended because we own a single share, Berry revealed that the company– which now pays him $10,000 a year as chairman– has retired all its debt and earned a profit last year of $570,000, nearly double what it earned the previous year.

Connerat is ready for his payday. Despite living in Clearwater, Florida, where he works in a bank trust department, he says he's trying to get back on the CPC board. But it's CPC he really wants in charge.

"I want a company that's nimble; I want a company that's progressive. Don't run as if it's 1959. I leave open the possibility that Mr. Berry has been negotiating with Wachovia all along, but I'm not going to take it for granted. Wachovia has proven progressive management. They didn't become the 3rd or 4th largest bank in the country by doing nothing."

***

As this story was going to press, Wachovia responded to Connerat by informing him that he didn't own enough shares to force his merger proposal onto the mailing to Wachovia shareholders.

#