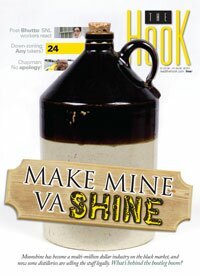

COVER- Make mine Virginia shine: Backwoods brew becomes big (and now legal) business

Known variously as "white lightning," "mountain dew," or just plain "firewater," there's no denying that moonshine has been a part of Virginia history for almost as long as there has been a Virginia. No less an august personage than George Washington operated a still at Mount Vernon. When Pennsylvania tried to impose a tax on the brew in the late 18th century, Scots-Irish farmers fled to the Blue Ridge hills to continue making their corn-based liquor unmolested. And during the era of Prohibition, it was the backwoods moonshiners who kept Virginia's whistle wet with their cheap, easy-to-make brand of booze.

Now, even as the clear, syrupy contraband continues to run down mountainsides throughout Appalachia, moonshine has seeped its way into places it's never been before: local ABC stores.

That's right: after centuries of operating in secret to avoid the taxman, some moonshiners have gone legit– and consumers are buying up and drinking down the brew with newfound interest. Meanwhile, state and federal agents say illegal moonshine operations have become multi-million dollar businesses, with distribution networks that run from rural Virginia to Philadelphia, Atlanta, and beyond.

What has caused more and more people to take a shine to 'shine? Theories vary, but there's no doubting that moonshine is having its day in the sun.

A 'shine of the times

Moonshine's new social acceptance can be seen all over the Commonwealth.

Culpeper's Belmont Farms Distillery ships bottles of its Virginia Lightning corn liquor to state-run Alcoholic Beverage Control stores across the state, including most of Charlottesville's branches. So respectable has the company become that the Virginia Tourism Corporation– the same folks who remind vacationers everywhere that "Virginia is for lovers"– features the distillery on its website, the History Channel profiled it in 2005, and in 2006, Belmont Farms entered a category that even Virginia Gentleman bourbon can't boast. Unlike the brand's A. Smith Bowman Distillery in Lexington, Belmont Farms is allowed to sell its whiskey on its own premises, thanks to legislation passed by the General Assembly and signed by Governor Tim Kaine.

The formerly illicit beverage is even becoming part of kid-friendly fun. Endless Caverns in New Market is planning to build the Virginia Moonshine Museum of the Shenandoah Valley. No word on when the project will come to fruition, but a website currently pleads, "If you have memorabilia from the Prohibition Era that you would be willing to contribute for an exhibit, please contact us." A call to Endless Caverns about the venture was not returned.

Even schools are getting in on the action. Since "speakeasy" is a term students are required to know on this year's seventh grade Standards of Learning exam on American history, Buford Middle School teacher Laura Merricks turned her classroom into a 1920s-era underground watering hole for a day. A local public school celebrating moonshine's heyday with 12-year-olds?

"The speakeasy is an SOL," says Merricks. "We're really clear with the kids that they all know what it is. We think they're old enough to differentiate between that behavior and what we're doing."

Going straight

Native New Yorker Joe Michalek became exposed to white lightning in the '90s, when he was a 20-something marketing executive for North Carolina-based tobacco giant R.J. Reynolds. However, it didn't take long for him to observe that moonshine's effects in his new home went beyond a mere buzz.

"For my work at RJR, I went to a lot of concert festivals and a lot of stock car races, and everywhere I went, somebody would always pull the moonshine out," Michalek says. "Whenever the moonshine came out, some people really wanted to try it, some weren't so sure, but it always got everyone's attention."

As he watched this behavior grow increasingly frequent, Michalek started to see green in those clear mason jars.

"In marketing, it's so rare to see a product that has the kind of mystique that gets a reaction out of 100 percent of the people," he says. "I wondered why wasn't anyone selling this legally?"

It turns out that nobody had tried. So in 2003, after six years of endless paperwork and government compliance meetings, Michalek quit his job and founded Piedmont Distillers in Madison, North Carolina, just 20 minutes south of the Virginia line, the only legal distillery in the state. Using an old-fashioned copper still outfitted with space age gadgetry, he began making and manufacturing Catdaddy, a moonshine made with a blend of other ingredients to give it a sort of vanilla flavor. It sold well enough, but Michalek knew in order to thrive, he'd need to make a straight grain whiskey, and he'd need the help of a Tarheel legend who knows a thing or two about kicking a moonshine operation into high gear.

'The Last American Hero'

No living American is more famously emblematic of the moonshine culture's outlaw spirit than NASCAR legend Junior Johnson. In 1931, when he was born in the North Carolina hill country of Wilkes County, his father, Robert Sr., was coping with hard economic times the same way most poor farmers did during the Depression.

"Making moonshine was the only way for anyone to make any money," says Johnson. "So my father grew enough corn to feed his family, and what was left over went into making moonshine."

Of course, the only reason farmers could make a profit from moonshine was that they neglected to pay the taxes imposed by state and federal governments hurting for cash.

"The tax on a gallon of whiskey was $11, and in my early days you could get a gallon of whiskey for $2," says Johnson. "There was no way you could pay the taxes on it and make any money, because $2 was already more than a lot of people could afford."

Indeed, $2 in 1939, the year Johnson began helping his dad beside the kettle, equates to $27.67 today.

While Johnson's primary duties in the family business had been stoking fires and filling jugs, Johnson found his true calling in 1945 when, at the age of 14, he got behind the wheel of a '34 Ford and started crisscrossing the state every night delivering hundreds of jars of his father's homemade hooch. The government's "revenooer" agents were never far behind.

In a scene right of the 1958 Robert Mitchum classic, Thunder Road, Johnson describes the life of a whiskey runner.

"You're on pins and needles the whole night," he says. "I'd make four or five runs a night, which meant hundreds of miles. You get sleepy at the wheel, but you're also under a lot of stress because you might go to jail. Then in the morning you'd go to sleep, and around dark, you're ready to do it again."

These weren't just any cars Johnson was driving. In his decade of avoiding the revenooers, Johnson drove several Ford models, all of which looked like any other car. But under the hood, he had a car that could outrun any in the police fleet.

"I'd give it a bigger engine, bigger struts, bigger wheels, bigger tires," he says. "There wasn't much you could do to the interior to hide what you've got except take out the seats and stack the jars about six inches below the glass. Of course, if you stopped, you were caught anyway."

But Johnson knew mechanics alone wouldn't keep him out of jail. So when he wasn't making deliveries, Johnson was on a remote dirt road experimenting with new driving techniques.

"They'd set up these roadblocks," he says, "so I found a way to throw the car into second, turn the wheel hard, and do a 180. I practiced it a lot, perfected it, and then didn't worry about it no more."

Thus was born Johnson's famous "bootleg turn," the hallmark of Johnson's legendary speed and evasiveness. But as stories of Johnson's illegal exploits spread, so too did his reputation as the top man in a new league he and other moonshine drivers had helped to popularize– the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing or NASCAR.

Soon, budding journalist Tom Wolfe picked up the growing interest in the sport, and 1965 made Johnson, his moonshining days, and his 11 months in federal prison in 1956 (he was caught tending to his father's still, not while driving) the subject of a 20,000+ word Esquire magazine article, "Junior Johnson Is the Last American Hero, Yes!"

Eight years later, Jeff Bridges starred as a fictionalized version of Johnson in the 1973 movie The Last American Hero, and Johnson's reputation as the world's most famous moonshiner was set for all time.

By 2006, Johnson was 75 years old, and after a long career as one of NASCAR's most successful drivers and owners, he was content to look after his cattle on his Wilkes County farm. But moonshine newcomer Joe Michalek had other ideas.

"I had always wanted to do something with Junior Johnson," says Michalek. "I knew if I could, it would be huge."

"I wasn't sure at first," says Johnson. "If I put my name on it, it's got to be the best."

But after Michalek and company brewed up some test batches of Johnson's dad's original recipe– but using newer technology– Johnson was persuaded to allow Junior Johnson's Midnight Moon to be put on the market.

Johnson says Midnight Moon, with a taste closer to vodka than to wince-inducing traditional moonshine, is a far cry from the stuff he delivered in the old days.

"It's much smoother," he says. "You just can't buy a better drink in the liquor store."

Is the new product moving as fast as one of Johnson's race cars?

"We sell an awful lot of it," says Michalek, smirking as he avoids naming an exact figure. Even in its new age of legal sales, it seems moonshiners still have their secrets.

Drinking under the table

While Johnson's in no danger of being cuffed this time around, plenty of others are carrying on his illicit legacy, and turning a major profit. In 1999, ATF agents busted Ralph Hale Sr. of Franklin County and 26 others for a moonshine operation that moved an estimated 1.5 million gallons over a seven-year period and generated an estimated $52.5 million in revenue.

In 2001, the Virginia ABC uncovered Junior Moran and Darryle Johnson's Rocky Mount still, from which one million gallons had been sold over the previous 12-to-18 months, grossing approximately $25 million.

And less than two months ago, the feds arrested six people on 31 felony counts in connection with a still in Halifax County. With a sales network extending as far north as Philadelphia, and judging from the 1,726 gallons of moonshine investigators confiscated, it appeared they were doing business comparable to Hale, Moran, and Johnson.

According to Buddy Driskill, the Virginia ABC agent in charge of catching moonshiners, moonshine's appeal to black market consumers boils down to simple economics.

"A gallon of moonshine costs $25, and a fifth costs $4," he says. "You're not going to find anything cheaper than that in a liquor store."

So how does Michalek – with 750 ml bottles of Midnight Moon on the shelf for $21.90 at the ABC store near the Hydraulic Road Kroger– hope to compete with such prices?

"It's like the craft beer movement or the success of higher quality liquors like Grey Goose and Patron," he says. "People are looking for something better."

Still, if you want to try to better the taste of Michalek's mix and share it with a small group of friends, it's not likely that you'll attract the long arm of the law.

"We're going after the ones who make millions of gallons," says Driskill.

Home distillers should be careful of their tools, however.

"Between 1978 and 1998, the majority of lead poisoning deaths in this country were caused by moonshine," says Dr. Christopher Holstege, a professor of emergency medicine at UVA. "So in 2003, when we found there started to be a high number of lead poisoning deaths in the Atlanta area, we got curious."

In his investigation, Holstege found that of the samples the Commonwealth confiscated from 48 different stills, 43 contained lead, with 29 exceeding the concentration the EPA allows in drinking water, some by as much as 400 percent. He says it's the result of the crude way many makeshift stills are constructed.

"Lead solder is real easy to come by and very malleable," says Holstege. "So when the alcohol mixes with the lead and gets heated, the particles get released into the alcohol."

Still, Holstege says the shine-curious probably have little to fear.

"If you drink it everyday for years, you run the risk of getting lead poisoning," he says, "but if you go have a drink of it tonight, are you going to be poisoned? No."

Shine on?

With health risks like these for the illegal brew and only recent demand for bottles with the ABC stamp, how long can white lightning makers stay in the black? The market will ultimately decide. What's for sure is that whether moonshiners are risking their necks in an age-old contest with lawmen or betting their savings on a new gimmick, only a few who get into the business will come out ahead.

"Most people don't have the guts to live the life I've lived," Johnson says, "and most people who have the guts don't have the sense."

President Reagan pardoned NASCAR legend and staunch Jimmy Carter supporter Junior Johnson for his 1955 federal moonshine conviction in 1985. Even with a racing career that included winning the Daytona 500, Johnson calls the pardon "the biggest thrill of my life."

PHOTO BY CHRIS NOBLE

Joe Michalek quit his job with tobacco giant R.J. Reynolds to found Piedmont Distillers and start making and selling moonshine legally.<

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

By law, Piedmont Distillers must keep recent samples available for government agents to test for impurities and alcohol content. Despite the use of lots of high tech gadgetry to make their moonshine, Piedmont still keeps its samples in mason jars.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

Will legal, more expensive moonshine sell? "It's like the craft beer movement or the success of higher quality liquors like Grey Goose and Patron," says Michalek. "People are looking for something better."

PHOTO BY CHRIS NOBLE

Johnson has a word of advice to prospective moonshiners: "Most people don't have the guts to live the life I've lived, and most people who have the guts don't have the sense."

PHOTO BY CHRIS NOBLE

#