NEWS- Old-fashioned sheriff: George Bailey rides into the sunset

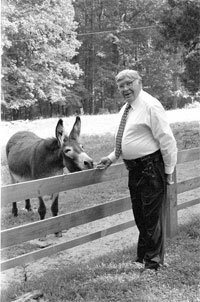

George Bailey photographed in 2004 at Bailey's Retreat in Ivy, where he lived with his wife, Elizabeth, and donkeys Jenny and Jose.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Former Sheriff George Bailey's favorite movie was A Wonderful Life– and not just because he shared the same name as the lead character played by Jimmy Stewart. Albemarle's George Bailey made no bones about it: He lived a wonderful life that ended January 4, when he died at age 80.

Bailey epitomized law enforcement in the county's recent, rural past when there could be two deputies responsible for covering the entire county. "George was a straight shooter," says former Charlottesville Police chief John deK. Bowen. "He was the picture of the old-time sheriff– a strong leader, respected, without the technology police have today."

Everyone knew Bailey, says Bowen, and Bailey "made a point of knowing people."

Bowen's friendship with Bailey dates back to St. Paul's Ivy, an Episocopal church eight miles west of Charlottesville on Owensville Road where, as boys, they both served as acolytes.

"He was seven or eight years older, and he always carried the cross, and we carried the candles," recalls Bowen. "So we go back to that when he first used his seniority."

In the Albemarle Bailey knew growing up during the 1930s, it was no big deal for him– at age 10– to hitchhike into town after church on Sunday to catch a movie at the Paramount. His parents "didn't think anything about letting us thumb into town," he told the Hook in 2004.

After a stint in the Army, Bailey returned to Albemarle and became a deputy in 1955. Bowen occasionally rode with him on patrol. "George always had a cigar, and his cigars were not always aromatic," remembers Bowen. "I'd say, 'How about tonight you just chew on it?'"

It was hard to both be the rural lawman and run the county jail, Bowen says: "George didn't take anything off anybody. You had to be firm and tough out there in the hollows and boondocks. Some of those places a radio wouldn't pick up. Back then, you were on your own."

In 1970, when Sheriff Walter Sherrod "Shirley" Cook retired, Bailey was appointed sheriff, and new-hire Terry Hawkins remembers walking into a hornets' nest, unaware of how contentious Bailey's appointment was. The deputies supported another candidate for sheriff, and when a justice upheld Bailey's appointment, "These deputies walked out," says Hawkins, who went on to succeed Bailey when he retired in 1987.

Bailey's tenure as sheriff spanned the years when the county was beginning to grapple with growth and move away from the "Andy of Mayberry" model of law enforcement. In 1983, the Albemarle Supervisors created a police department just one day before a July 1 law went into effect that would have required a referendum to make the change– "because it would have failed," says Hawkins. "Police departments are much more expensive to run. The reason they do it is for control, because [supervisors] have no control over an elected sheriff."

Bailey served as the county's first police chief for a year, and returned to the stripped-down sheriff's post, maintaining court security and transporting prisoners.

"I don't think there's any doubt about it," says Bowen. "Politics were involved in converting to a police department."

But politics is an arena where Bailey thrived, and even after he left office he was involved in local and state elections. "At 80, he kept up with everything and knew everybody," according to just-elected Sheriff Chip Harding, who says that Bailey encouraged him to run 15 or 20 years ago.

Bailey advised Harding that if he was going to run, he needed to get involved with the local party first, advice Harding heeded. "He was there on a cane when I announced February 13," Harding says.

A couple of weeks before the election, Bailey called Harding at home. "He'd been by a couple of country stores, and he felt I needed to have more of a presence, so I went out there," says Harding, again following Bailey's advice.

As Albemarle's top law enforcement officer, Bailey was often in the headlines, but there was one bust that still riled him 30 years later. In 1976, state police raided a cockfight at a Garth Road estate and arrested 11 prominent citizens without advising Bailey– who was there.

Even today, while dogfighting can put an NFL star behind bars, cockfighting remains legal in Virginia. Betting on it, however, is not legal, and when the cops descended upon Ingleside Farm, it was a scene out of old Albemarle. Bowen says Bailey never talked much about it.

"They were his friends– people he knew," says Bowen, who says he's been to one cockfight in his life. "It was a clique, and they were supporters of his. That would be embarrassing to him. I would be embarrassed."

Coming into a jurisdiction without letting local law enforcement know is problematic, Bowen says: "When they do that, they signal they don't trust you as head of the agency."

Bailey remained sheriff for another 11 years after the raid, and the lawmen who knew him emphasize his honesty and bravery– and his influence as sheriff.

When evaluating deputies for promotion, Bailey didn't want to know how many tickets they'd written, but how many cases they'd taken before the grand jury, says Hawkins.

"He was very rigid on personal appearance, and a couple of times I was downgraded because my hair was too long," laughs Hawkins (who still maintains that he didn't have long hair).

And whenever Hawkins expressed his frustration, he says, Bailey would open his desk drawer and say, "Do you know what this is, Hawkins? It's applications, and plenty of people would love to have your job."

But Bailey also was aware the department needed to move forward, and he sent Hawkins to the more "prestigious" schools for training, and okayed the area's first drug task force.

"He's the last of a dying breed of old-fashioned sheriff," says Hawkins.

Bowen describes Bailey as a "very conservative man," personally, politically, and in the way he ran his office, which was on a shoestring. "He was always battling the county," Bowen says.

"You pretty much know where George stood on issues," says Bowen. "He'd let you know."

#