NEWS- Fresh hope: Drug shows promise for ALS sufferers

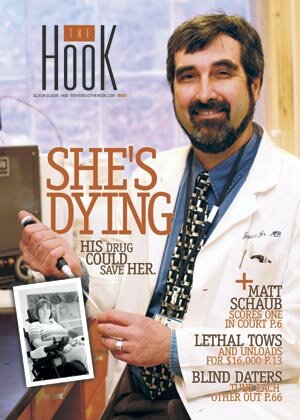

James Bennett

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

In 2004, a small and desperate group of terminally ill patients pleaded with UVA hospital not to pull the plug on an experimental drug they claimed could be their only hope. More than three years later comes the first scientific evidence they might have been right.

In the January issue of the medical journal Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, UVA neurologist and researcher James Bennett has published his first article on his research into the drug known as “R-(+)-pramipexole." His findings: the drug is safe, even at higher doses than given to the original group. More importantly, it just might work.

***

Tucked away in his office in UVA's McKim Hall on Friday morning, February 8, Bennett is guarded about the implications of his research. His study, he says, supports his early hypothesis that the compound is safe, even at the higher doses required to protect nerve cells, which rapidly die during the devastating course of ALS. (The compound is the chemical mirror image of the Parkinson's drug Mirapex, which would be toxic at high doses.)

Once they are diagnosed with ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease, most patients die within a few years, as they lose the ability to walk, talk and, eventually, breathe. But while Bennett seems confident of the drug's safety, he's far more cautious when talking about its efficacy, in part because the number of patients in his study– 27– is too small to allow him to make generalizations.

Still, "I'm optimistic," he says, citing "positive trends" and indications in his research that cell damage was slowed, even if slightly. "It justifies going forward," he says.

That's something ALS sufferers across the country are hoping for.

"We're desperate," says Debbie Miller, who cares for her ALS-stricken husband in their Florida home. "We keep running into dead-ends."

Miller, who contacted the Hook, says news of pramipexole has spread through the ALS community across the country, and she's hoping the drug will become widely available soon.

That's something a small Pennsylvania-based drug company is aiming to make happen. In June 2006, Knopp Neurosciences licensed Bennett's compound and committed to developing the drug commercially. Knopp, which has already committed $20 million in funding, has also conducted its own, larger scale, Phase I trials to establish safety. This spring the company is commencing Phase II studies– for safety and efficacy– at yet-to-be-named locations around the country.

According to Knopp spokesperson Tom Petzinger, "proof of concept" studies could begin within a year, making way for wider Phase III studies to confirm any positive findings. If it is found to be effective in further studies, it will be reason to rejoice– for patients, certainly, but also for Bennett, who has faced numerous obstacles in pursuing his research.

In 2004, Bennett conducted a small Phase 1 study with a group of 15 patients at UVA. He had approval to dose patients with the compound for eight weeks to identify any possible side effects.

During those eight weeks, however, more than half the patients reported slight improvements in their condition. As reported in the Hook's February 24, 2005 cover story, "She's dying: His drug could save her," one woman claimed to regain the use of her left hand; another said she was able to climb stairs.

But such "anecdotal evidence" did not immediately sway UVA's Human Investigation Committee, the ethics board overseeing human research. The Committee refused to allow the patients continued access to the drug after the eight weeks, citing safety concerns resulting from a lack of research on animals.

An intense battle ensued, with Bennett's patients demanding access to the drug.

"For a person with a terminal illness, risk is not the same as risk applied to a healthy person," explained one patient. "If you have ALS, you're going to die, period."

Eventually, Bennett won permission from the FDA to continue dosing his patients on a "compassionate use" basis, but all of those the Hook spoke with have since died. UVA also reinstated Bennett's ability to dose humans once he had done further animal testing.

Red tape hasn't been Bennett's only challenge; he's also dealt with criticism. In April 2006, the Wall Street Journal published an article about Bennett and his drug, with critics suggesting he had engaged in the ethically questionable practice of asking patients to fund the research. Bennett said the allegation is "absolutely untrue," but he noted that several people who had already donated money were also taking the drug. Those people, he explained, were simply informed when another round of fundraising began. Bennett says he now has no financial stake in the drug's commercial development.

Although Bennett's role as a clinical investigator of the drug is coming to an end, he says his fight against ALS is not. This year, he's on a sabbatical paid for by the National Institutes of Health to develop the use of human embryonic stem cells for use in neurodegenerative diseases like ALS.

His own research, coupled with a recent discovery by Italian scientists that shows the bipolar treatment Lithium may also slow ALS's progression, give him hope that the disease may not always be the terrifying death sentence it is today. Instead, he believes it will become like HIV/AIDS, a "chronic disease that you live with."

As for the challenges Bennett has faced developing the drug over the last several years, he's upbeat– and hopes his experience will inspire other academic researchers to make medical breakthroughs.

"It certainly had bumps," he says of the process, "but it shows it's possible to do this."

The original version of this story incorrectly stated the timeline for future studies conducted by Knopp. It has been corrected online. This version also clarifies that Bennett's compound is the chemical mirror image of the drug Mirapex.–ed.

#