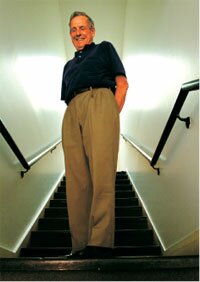

NEWS- The Mitch: Van Yahres walked the walk

Charlotteville's best-known arborist stood up for the poor– and for the wrongly felled tree.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

He was a familiar sight on the Downtown Mall. For years, his 57th District legislative office was there. On Friday nights, he frequently could be spotted out on a date with Betty, his wife of 60 years. In fact, it could be argued that Charlottesville wouldn't even have a Downtown Mall were it not for Mitch Van Yahres, one of two City Councilors who voted to brick over Main Street in 1974.

Van Yahres, 81, won't be seen on the Downtown Mall anymore. He died February 8 following complications from surgery for lung cancer.

In more recent decades, he was better known as Charlottesville's delegate to the General Assembly, a seat he held for 24 years, a liberal Democratic voice in an increasingly conservative body.

In 2005, the General Assembly had become a less congenial place for the longtime Dem, who saw no shame in being called a liberal. "The environment has changed, and it's not for the good," he told the Hook after declining to seek another term at age 78. "It's not a pleasure to be there. It used to be you were able to have friends on both sides of the aisle. There was a political spirit of compromise. Now you have to win battles."

Connie Jorgensen was Van Yahres' legislative aide for almost seven years. One of her favorite Mitch stories is about how he got the General Assembly to apologize for eugenics and the involuntary sterilization of those deemed "genetically inferior," a movement that started in 1927 and didn't stop until 1974, after 7,500 Virginians had undergone the procedure.

"He didn't know about it," says Jorgensen. "He read a series in the Times-Dispatch. He saw a wrong and worked to correct it."

Van Yahres drafted a resolution in 2001 in which the General Assembly expressed its "profound regret" for the involuntary sterilizations, knowing full well the legislative body was not about to apologize, says Jorgensen. Within a few months, Governor Mark Warner apologized for the Commonwealth's eugenics laws.

In a sea of lawyers, Van Yahres was the General Assembly's only tree surgeon and became head of the agriculture committee. He got perhaps the most flak for his support of decriminalizing the cultivation of industrial hemp, a multi-use plant that resembles marijuana. "He didn't get very far with it," Jorgensen says, "but he believed in it."

A Long Island native, the man known simply as "Mitch" moved to Charlottesville in 1949 and started his tree surgery business. Even after retiring from Van Yahres Tree Service, he remained a tree advocate, most recently chastising the city for cutting down a deodora cedar to make way for the Pavilion and Transit Center in 2004, as well as for taking out another 20 or so smaller trees toward Belmont Bridge. He had planted the cedar in front of City Hall in the 1950s.

"Those little trees could have been saved," said Van Yahres. "We think of ourselves being so sophisticated, but that was as brutal a thing as could be done."

Van Yahres was elected to City Council in 1968 and served as mayor from 1970 to 1972. "He was fair and concerned about race," remembers Charles Barbour, the city's first black mayor, who served on Council with Van Yahres, joined him in that historic Mall vote, and served at a time when Fry's Spring Beach Club was still segregated.

"He would not attend a function where I as a black would not be welcome," says Barbour. "He was the first modern day mayor who did a lot for the city and set the stage for all the good things we have today." (Barbour also recalls that when refreshments were served, he and Van Yahres were always the first to get to the peanuts.)

Former City Councilor Meredith Richards did fund raising for Van Yahres' reelections in 1993 and 1995. "He never raised a lot of money– he raised a little," says Richards. "He was indifferent to fund raising. He'd already sworn off tobacco money."

When he had an oppenent in 1993, he saw the value in raising money– "so he could pass it on to other candidates with his Road Back PAC," says Richards.

"Mitch stayed very close to his community and to his constituents," she adds. "Everybody knew Mitch. Any time of day you could come into his office and he'd drop everything."

Van Yahres was also known for his fashion– a propensity for plaid shirts with the sleeves rolled up, says Richards. That look faded after she and Betty planned a surprise party and 300 people showed up wearing plaid shirts. ("Maybe he decided his plaid days were over," Richards muses of his later penchant for polo shirts.)

He lived a couple of blocks off the Mall, walked everywhere, and chatted with everyone, Richards says. "He was a good ole-fashioned politician."

Even in death, Van Yahres' political side was obvious in his obituary, which urged "his friends, which included everyone who met him, to make a healthy and significant contribution to the campaign of Barack Obama" in lieu of flowers.

"What he was really about was letting people be heard," says Jorgensen. "Walking down the Mall took two to three times longer than ordinary because people had to talk to Mitch. I can't tell you the number of times we were late."

Mitch Van Yahres won't be walking on the Downtown Mall anymore. But his footprints remain.

#