Reservoir dogged: A $142 million boondoggle?

Dam critics: Five of the six members of Citizens for a Sustainable Water Plan (clockwise), Rich Collins (in cap), Francis Fife, Kevin Lynch, Betty Mooney, and Joe Mooney, gather at the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir.

PHOTO BY JAY KUHLMANN

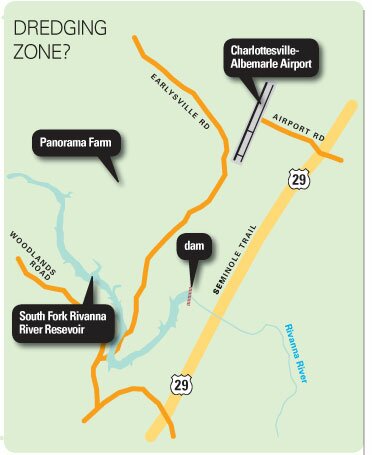

Every day, a little more sediment seeps into the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir, reducing its capacity to quench the thirst of our growing population. Dredging it, however, will cost millions, mostly for trucking away the dirt.

Meanwhile, just a couple of miles away lies the Charlottesville-Albemarle Airport, which wants to expand its runway and plans to spend $15 million of its $50 million budget to... truck in dirt.

Why can't these two quasi-governmental bodies get together to save each other millions of dollars while solving the local water crisis? A Hook investigation finds they haven't really tried– that no serious studies have been conducted to discover if dirt-swapping might be a viable solution to both their problems. And dredging supporters allege the company that told the local waterworks to dam its way out of disaster might have a conflict of interest.

The solution?

The 2002 drought– the one that shuttered car-washes and relegated haute cuisine to plastic plates– prompted widespread talk of a solution to our water problems. But a late-2004 cost estimate of $145 million doused all enthusiasm about dredging the Rivanna Reservoir. Saving that water source was abandoned as impractical.

Today, the official plan to meet the area's water needs for the next 50 years costs about the same– the current estimate is over $142 million– but it includes a controversial dam that would inundate 133.5 acres of forest and trails in a near-town hiking area and a snake a pipeline for 9.5 miles across the rolling hills of Albemarle County.

This Ragged Mountain dam and pipeline plan has many official blessings. In June 2006, both Charlottesville City Council and the Albemarle Board of Supervisors unanimously approved it. And less than three weeks ago, on February 11, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality issued a permit to proceed. But not everyone in area is clinking their water glasses in celebration.

A small group of citizens has come forward to decry the dam/pipline plan as too costly, environmentally unsound, and not fully vetted in the public process. "It's too risky, too expensive, and too railroaded," says critic Rich Collins, one of those raising some troubling questions about the official solution to the area's water woes that involves creating a new, vastly expanded Ragged Mountain Reservoir.

It would be easy to dismiss the group as malcontents who weren't paying attention during the numerous public meetings leading up to the widespread approvals. However, these individuals are prominent citizens– including a former mayor and a vice mayor– who are well-versed in the area's water history. Collins is a former chair of the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority, the agency charged with keeping the water flowing to Charlottesville and Albemarle County taps, as well as a newly elected director of the Thomas Jefferson Soil & Water Conservation District. Another, Kevin Lynch, even voted to approve the plan while he was on City Council.

So why is the group, Citizens for a Sustainable Water Plan, trying to throw a wrench into the plan that advocates say was carefully crafted, has the support of local governments– and perhaps even more importantly– of some local environmental groups? Aren't they sowing dissension with their green brothers?

"Many well-informed citizens have questioned the accuracy of the one dredging cost study done thus far," says member Betty Mooney, a former city planning commissioner. "We need a second opinion."

Mooney's husband, Joe, a former Charlottesville School Board chair, is another member of Citizens for a Sustainable Water Plan. So is former School Board member Dede Smith. And so is Francis Fife, former Charlottesville mayor and– like Rich Collins– a former chairman of the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority.

These citizens are united in the belief that the new dam/pipeline plan will outstrip budget estimates and that the dredging of the South Fork reservoir was scotched by staggeringly high estimates from a company, they allege, whose business is building dams and pipelines, not dredging.

Betty Mooney pulls up the website of Gannett Fleming, the company that estimated the South Fork dredging would cost between $127 and $145 million and that serves as the consulting engineers for the proposed 112-foot-tall Ragged Mountain dam.

"Look at their specialties," says Mooney. "Do you see dredging?"

Authority director Tom Frederick defends the company the Authority hired for its studies, and also its December 2004 report with the $127 to $145 million dredging price tags.

"The estimate was put together by a multi-national engineering company with broad experience, including people with expertise in dredging," says Frederick. "They sub-consulted some of the work, including with contractors in the local community. That's how engineers work. They talk to other people."

The critics think they should have done a bit more listening.

The silting of South Fork

In 1966, the city of Charlottesville dammed the South Fork of the Rivanna River to form the urban area's largest source of water. From an original capacity of 1.7 billion gallons, the reservoir has to date lost about 545 million gallons to sedimentation, about one percent of its capacity each year. An Authority-commissioned study finds that by the year 2055, the reservoir will hold just 20 percent of its original capacity.

According to an Authority fact sheet, restoring the South Fork reservoir to its original capacity would require the removal of approximately 1 billion gallons of accumulated sediment, or 5 million cubic yards. That translates to hauling away 67 truckloads a day.

"Dredging was studied so they could eliminate it," counters Lynch, who says he's skeptical of the Gannett Fleming estimates. For instance, the report is based on dump trucks with a six-cubic-yard capacity.

"Bullsh**," he says. "Regular dump trucks can haul 10 to 12 yards. I don't know dredging, but I know how many yards a dump truck can hold.

"Gannett Fleming has never done a dredging project," Lynch continues. "They've done lots of dams. If I want someone to work on my car, I don't take it to a car compaction yard. Anyone with common sense says 'Why not get someone in the business to give an estimate?' and 'Hey, it looks like the airport needs 400 million gallons of fill, which equals two million cubic yards.'"

Dredging two million yards from the South Fork reservoir "is like low-hanging fruit," says Lynch. "We could get 15 years additional water supply. It's a no brainer."

Gannett Fleming, based in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, declined to comment beyond releasing a statement pointing to its expertise.

"Our reputation as national leader in the water resources and environmental fields" writes Gannett Fleming's Robert A. Kline Jr., "is based on our ability to be comprehensive in our approach and objective in our recommendations."

Go CHO?

The Charlottesville Albemarle Airport, located two miles away from the Rivanna reservoir, has made no secret of its desire to attract larger jets by extending its main runway. Just last month, airport director Barbara Hutchinson told the Daily Progress that she has identified public funding sources that might cover half the $50 million cost of extending the runway 800 feet.

So what about the sediment-loaded reservoir as a source?

"This was looked at three or four years ago," says Hutchinson. "It was determined it was not feasible to move forward."

Further questioning, however, reveals that Hutchinson is referring to the Rivanna Authority's own decision to call a halt to exploring the possibility of dredging the reservoir.

The Gannett Fleming report was inconclusive regarding the suitability of using the reservoir's silt for CHO's runway and called for further study. But given that the idea of dredging has been abandoned, Hutchinson says, the airport has no plans to study the soil.

Her colleague at the Rivanna Authority is similarly disinclined toward further study.

"If the airport wants to study it, fine," says Frederick. "But why would you want to hold up a water supply plan that has been permitted?"

Uh, perhaps to save tens of millions of dollars?

Hutchinson says there are too many variables about whether the material would be suitable– it would have to be approved by the FAA– and whether the timetables would work.

"How would you get it from the reservoir to the airport?" asks Hutchinson. "We need two million cubic yards– that's a lot of truckloads. Can you pipe it? Would landowners approve a right of way?"

Panorama Pay-Dirt

It turns out that the biggest piece of land between the airport and reservoir is 850-acre Panorama Farm, owned by a family that just happens to be in the soil business.

"I told them we may be interested in stockpiling," says Panorama Farm co-owner Steve Murray, talking about negotiations surrounding the dredging proposal about five years ago.

One of eight brothers, Murray grew up on the farm while his father, James B. Murray Sr., was serving in the Virginia General Assembly. Besides hosting several high school cross-country running races each year, the younger Murray now spends his time exporting a composted product he makes from leaves and chicken manure. It's called "Panorama Pay-Dirt," and he sells it for $30 per cubic yard.

During the 2002 drought, Murray watched the reservoir, which abuts the farm, drop so low that about 20 acres of lake bed dried out. That's when he contacted the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority, which was still considering dredging at the time. Discussions went on for about two weeks, he says.

Authority director Frederick says the negotiations collapsed because the sites Panorama would allow for de-watering were sensitive forest and stream zones that would probably not win the approval of environmental regulators.

Today, Murray is not advocating taking dredged material on Panorama Farm, and he says he would not be willing to pay for it because of several hurdles such material presents, including tying up valuable land during the multi-week drying process. Handling the sediment, he says, would be a whole new business about which his family would have to think long and hard.

"There are lots of factors we'd have to consider," he says. "It would change the landscape. Dirt's heavy. It weighs twice as much as compost. And the content of the material coming out of the reservoir— we'd want to know what it is."

While the exact composition of the material accumulating in the Rivanna Reservoir may merit further testing, Gannett Fleming's initial analysis found a nearly even mix of sand and silt– with only trace amounts of most heavy metals and other contaminants.

Given that one of Gannett Fleming's estimates budgeted tens of millions of dollars just to truck the dirt away, Betty Mooney is flabbergasted that the airport option hasn't been exhaustively explored, especially when the airport is looking at spending $15 million to purchase fill.

"We have talked to a dredging company that has built runways on fill," says Mooney. "JFK [International Airport] was built on fill from dredging. How could our bureaucrats not want to save us millions and millions of dollars?"

Dredging primer

The cheapest way to dredge is the hydraulic method– pumping the sediment out– and that's a method frequently used by Anthony Cavo, third-generation owner of Cavache Industries. He says the cost of dredging a body of water depends on such variables as the depth, the type of material, and the distance to stockpile.

Sand and biological materials are easy to pump, he says.

"You have to get rid of the silt," he says. "Usually when you're dredging, silt and biological material sit on top of sand. Once you get through the silt, basically it's sand." And after the water drains from a cubic yard of silt, the dirt shrinks to a quarter is original size.

Cavo's thumbnail estimate for a hypothetical job to hydraulically dredge the South Fork reservoir and pump the sediment off-site would be $8 to $9 a yard using a smaller dredge, $5 to $6 a yard if access were available for a big dredge. The water needs to go somewhere, and if the material had to be trucked, that could add another $2.50 a yard.

Using Cavo's worst-case scenario– $9 a yard to dredge plus $2.50 a yard to haul— puts removal of the 5 million yards of sediment at $57.5 million, about 60 percent less than Gannett Fleming's estimage.

The preliminary estimate from Gannett Fleming suggests that the Rivanna's sediment, coming from a semi-rural area, does not likely contain hazardous materials. And three samples the company tested revealed that the sediment may average a 50-50 percent mix of sand and silt/clay.

"That would make good fill," says Sam Artino, owner of another company, National Hydraulic Dredging, in Clearwater, Florida. And in a water supply, "You're not going to find heavy metals or PCBs."

Artino recently worked on a project at the Tampa Airport, where sediment was dredged, pumped to a containment area, and then incorporated into fill.

He acknowledges that high levels of organic materials– which the Rivanna is suspected of having– take longer to dry out, but while Gannett Fleming called for a 40-acre dewatering field, Artino doesn't see why drying all five million cubic yards should require more than 15 acres of land.

And once you start talking millions of yards, Artino says, economies of scale kick in. He puts the price tag at $1 to $1.50 a cubic yard to dredge with an additional $5 to $6 per yard to pipe it off-site. So the combined maximum– even allowing $1 million for mobilizing the equipment– would be about $38.5 million. That would be $100 million less than Gannett Fleming predicted.

"If someone says taking out five million yards is going to cost $100 million, they're way off base," says Artino.

Artino is also perplexed by Gannett Fleming's claim that Charlottesville-area contractors mustered so little interest in the dredged material that the consultants went on to budget up to $80 million for disposal of the fill.

"I don't know about Virginia, but in Florida and South Carolina, fill is at a premium," says Artino. "I could sell it for $5 to $10 a yard."

Indeed, the expansion of the Charlottesville-Albemarle Airport appears– since it's seeking two million cubic yards for $15 million– to value fill exactly halfway through his range: at $7.50/yard.

And pumping fill two miles– the distance from the Rivanna reservoir to the airport– isn't a big deal, Artino says, adding, "I'm pumping a mile and a half now in Charleston."

If Artino's estimates are correct, and the airport can accept some or all of the fill, the cost to dredge the Rivanna could dive from $145 million to $38.5 million. And if the Airport would pay for its portion and a nearby landowner would take the rest, the net cost to the Authority might be just $26.5 million.

But Cavo stresses, "There are a lot of variables."

"Dredging is a very, very complicated process," says Authority director Frederick, mentioning Albemarle's rolling hills and reluctant land owners. He cautions against getting too excited about the dramatically lower cost estimates offered by these dredging companies, both of which admit that they have not specifically looked at the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir.

"A dredging company may have a conflict of interest," Frederick recently said at a panel discussion on the water supply plan. But Citizens group member Lynch points out a potential conflict in official studies by a company that's in the dam-building business.

"When they want you to do something, they make the numbers as low as possible," he says. "When they don't, they make them as high as possible."

Ragged Mountain revisionism?

Critics of the new citizens group say that anyone revisiting the notion of dredging today wasn't paying proper attention in the past.

"Others were," says Ridge Schuyler, who directs the local chapter of the Nature Conservancy and who is widely acknowledged as the architect of the South Fork-to-Ragged Mountain pipeline plan.

After the 2005 uproar over a proposal to run a pipe all the way from Scottsville to carry water pumped out of the James River, Schuyler says expanding the Ragged Mountain Reservoir will achieve three goals the community seeks: safe drinking water, a source within the local watershed, and restoration of the flow to the Moormans and Rivanna rivers.

"We thought those were mutually exclusive," says Schuyler. "This [plan] was the ecological equivalent of pulling a rabbit out of a hat."

His dam/pipeline plan earned the support of a veritable "who's who" in the green world: Piedmont Environmental Council, Southern Environmental Law Center, Friends of the Moormans, the Rivanna Conservation Society, and Advocates for a Sustainable Albemarle Population.

In the course of weeding out the alternatives, it was pointed out that the century-old Ragged Mountain dams, built in 1885 and 1908 as the city's first reservoirs, were considered unsafe if a major flood overtopped them and eroded surrounding dirt.

Although that's been the case since the 1970s, Authority director Tom Frederick says the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation has given the Authority a 2011 deadline to fix the problem. But according to Collins, it could be fixed for less than $3 million by simply widening the lower dam's spillway.

"We were ballyhooed into a possible dam failure," says Collins. "The citizens of Charlottesville and Albemarle were forced into a hugely expensive operation without consideration of other alternatives."

He contends the current expanded Ragged Mountain plan that raises the water level 45 feet is the result of a "phony" deadline. "All of a sudden, a modest effort to widen the spillway became 'tear down the existing dam and flood the area,'" he says.

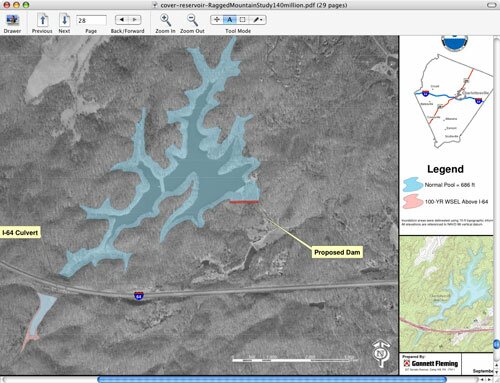

Flood the area indeed. Besides several hiking trails in the Ragged Mountain Natural Area, the new 204-acre Ragged Mountain lake would stretch south all the way to I-64 and require a $689,000 culvert that would actually bring a tip of the lake under the Interstate.

Kevin Lynch remembers how opponents fought the Western Bypass for coming too close to the existing reservoir. "You can't get any closer than under I-64," he says.

Lynch defends his 2006 vote, when City Councilors and Albemarle County Supervisors voted unanimously for the Ragged Mountain Reservoir plan, because he expected it to be a phased action, starting with raising the dam just 15 to 20 feet.

"That would cover us for decades," he says. "What gets me upset now that it's approved is we can't really phase, and we need 140 million bucks. We approved a 50-year plan. Having a sense of what you're going to do in 50 years doesn't mean you have to capitalize it this year."

Frederick contends the new dam at Ragged Mountain, which raises the water level 45 feet, "is in the spirit of phasing" because it will take years to fill the larger reservoir. He says it doesn't make financial sense to raise the dam incrementally.

–from a Charlottesville Tomorrow report

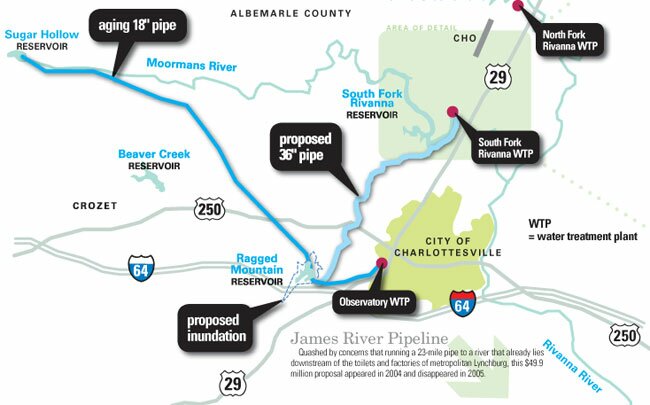

Another part of the approved plan includes upgrading the treatment plant at Observatory Hill. Ultimately, the pipeline from Sugar Hollow Reservoir, which fills Ragged Mountain, would be disconnected, and the long-blocked Moormans River would be allowed to flow free, its water ending up in the Rivanna Reservoir.

But that's not going to happen anytime soon. Because Ragged Mountain has such a small watershed, Sugar Hollow and its aging pipeline will continue to feed that reservoir.

Some plan critics fear that both the Sugar Hollow and Rivanna reservoirs will be abandoned and allowed to silt up, an action that does not constitute sustainability. Frederick insists the two reservoirs will remain part of the water supply– although estimates for the Ragged Mountain alternative include no funding for the still-silting other two reservoirs.

The Ragged Mountain dam and pipeline estimates include $17 million in engineering fees; Gannett Fleming won a competitive bid to engineer the project.

While Citizens for a Sustainable Water Supply fear the waste of tens of millions of dollars and 133.5 acres of natural area at Ragged Mountain, the City of Charlottesville appears to still hold some cards in this debate. According to the plan, the city would be compensated just $549,000– $4,114 per acre– for the rolling tracts of forest that disappear first under bulldozers and then under water.

Lynch says that although the Authority could technically become the owner, the responsibility for this $142 million scheme will ultimately fall to the 47,000 water-using households who saw their rates double in 2003.

While the cost of the system works out to over $3,000 per household, Frederick says it won't be allocated that way. He proposes a three percent wholesale rate increase to pay for the new Ragged Mountain dam, but he acknowledges that to build the pipeline from South Fork to Ragged Mountain would necessitate another rate increase.

Lynch raises another question: "Who's setting our water policy? It's not supposed to be the Rivanna water authority. It's supposed to be City Council and the Board of Supervisors."

City Council and the Board of Supervisors approved the Ragged Mountain plan in June 2006 without public hearings.

No elected officials serve on the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority board, and, Lynch says, "Talking to my fellow councilors, I found very little interest. I can't understand City Council's complacency.

"People have to wake up and realize they're about to be taken to the cleaners by the Rivanna water authority," Lynch warns. "This is poorly planned and leaves us with a more vulnerable system at a greater expense."

"We listened to the public," counters Frederick, who notes that when the Ragged Mountain alternative was announced in April 2006, 27 of 28 people attending the Authority meeting favored the plan. "It was almost a love fest," says Frederick, "a feeling in the community that after 30 years, it was the right plan."

Citizens for a Sustainable Water Supply acknowledge that there were plenty of public meetings, but they say that the Ragged Mountain/South Fork pipeline plan did not come up until the 9th public meeting in October 2005.

Frederick points out the Ragged Mountain plan was unanimously approved by all boards, both elected and appointed, both local and statewide. "I think," he concludes, "it's a model plan that balances stream flow and human needs that will be used by the DEQ in the future."

Rich Collins and Kevin Lynch stand below the dam that holds the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir. In 2002, a $13-million plan called for dredging the reservoir and putting a four-foot crest atop the dam to increase capacity.

PHOTO BY JAY KUHLMANN

The new dam will double the size of the Ragged Mountain Reservoir, ensuring a 50-year water supply– and views from I-64.

MAP COURTESY RIVANNA WATER AND SEWER AUTHORITY

One of Gannett Fleming's estimates to dredge the South Fork reservoir included $80 million to dispose of the sediment if no one wanted to use it.

MAP COURTESY RIVANNA WATER AND SEWER AUTHORITY

Rivanna Water and Sewer chief Tom Frederick says the Ragged Mountain Reservoir has been embraced by local environmental groups and highly scrutinized by regulatory agencies– which gave the plan the thumbs up– while he calls the plan's critics a "small handful of people."

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

#

COVER MAPS- Silt story: The water world of Charlottesville and Albemarle

Today's network of reservoirs could get a major overhaul with a new emphasis on Ragged Mountain's reservoir under the $142 million, 50-year water plan.

MAP BY ALLISON SOMMERS

MAP BY ALLISON SOMMERS

Ragged Mountain Reservoirs

Yup, they're plural for now, but they won't be if the Authority gets its way. The first of these two dams was constructed of earth and on-site stone for a combined Charlottesville/UVA population of under 10,000. Phase II came 23 years later with a concrete structure called Mayo's Rock Dam. Today, a plan calls for submerging both– along with several miles of hiking trails– behind a new mongo dam that would rise 112 feet high– 45 feet taller than Mayo's Rock Dam– and put about 200 acres under water.

Size: 65 acres

River: unnamed tributary of Moores Creek

Elevation: 640 feet

Dam height: 67 feet

Built: 1885 & 1908 for $283,000 total

Original volume: 620 million gallons

Today's volume: 514 million gallons

Capacity loss: not so much

Watershed: 1.9 square miles

Buzzkill: By the 1920s, algae growth, low recharge rate, and unpalatable taste led the city to built its first Sugar Hollow Dam.

Sugar Hollow Reservoir

First dammed in 1925 and combined with a 13.5-mile pipeline to the city, this edge-of-Shenandoah lake handled Charlottesville when Ragged Mountain's taste and capacity problems became evident. Even during the drought of 1930, it supplied enough water. And its 1947 replacement is an Albemarle County landmark. But due to a 1985 landslide and myriad other capacity-challenging incursions, it was bladdered in 1999.

Size: 51 acres

River dammed: Moormans River

Elevation: 975 feet

Dam height: 77 feet

Built: 1925 for $513,000; 1947 for $595,000

Original volume: 360 million gallons

Today's volume: 360 million gallons (with inflatable bladder)

Capacity loss: plenty, but reclaimed via bladder

Watershed: 17.5 square miles

Buzz: played leading role in 2007 film Evan Almighty

South Fork Rivanna Reservoir

The primary source of water for the urban area, it has the largest watershed of all the local reservoirs, but it has always been known for turbidity, aka cloudiness, and siltation.

Size: 366 acres

River dammed: South Fork Rivanna, of course

Elevation: 382

Dam Height: 60 feet

Built: 1966

Original Volume: 1.7 billion gallons

Today's Volume: 1.155 billion gallons

Capacity loss: about 1 percent annually

Watershed: 259.1 square miles

Buzz: Rowers zipping by add to scenic beauty.

source: RWSA documents

Beaver Creek Reservoir

Built for the town of Crozet and a big frozen-dinner factory called Morton Frozen Foods, which had opened a decade earlier, this scenic waterway "grew" in September 2000 when the 500,000-square-foot factory/warehouse– by this time known as ConAgra– closed its doors. Today, the biggest drinker of this Crozet-only reservoir is ConAgra's thirsty replacement: Starr Hill Brewery.

Size: 104 acres

Built: 1964

Today's volume: 521 million gallons

Buzz: The lake is open for fishing, and 115 acres of lush land around the lake draw picnickers as part of the County's parks system.

Buck Mountain Reservoir - never built

The Authority bought several hundred acres of the land it wanted to flood in Free Union in 1983 and planned a $107 million lake as the solution to our impending shortage. But the scheme was stopped dead in its tracks by the discovery of Albemarle's own version of the Spotted Owl, Pleurobema collina, a tiny mollusk commonly known as the James River Spinymussel, so the Authority de-listed the proposal in 2004.

James River Pipeline

Quashed by concerns that running a 23-mile pipe to a river that already lies downstream of the toilets and factories of Lynchburg, this $49.9 million proposal appeared in 2004 and disappeared in 2005.

#