COVER- Stacking the decks: Will new parking decks cure parking woes?

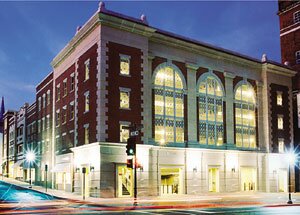

Ahead of the curve: Built in 1976, the Market Street parking garage– with 450 public and 50 private spaces (city police mostly)– is nearly unrecognizable as a deck from a distance and provides a seamless entry onto the Mall for pedestrians– not to mention a glass elevator that's always been a favorite with kids.

PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

As urban structures, parking decks have always been hard to warm up to: massive and nondescript on the outsides, they are often as dark and bewildering as caves inside. In countless films and TV shows, they're presented as sinister labyrinths, settings for illicit rendezvous, murders, violent car chases, shoot-outs, stalkings (heroine walking, hears noise, looks around to see nothing, walks faster– can she unlock the door in time?). An entire episode of Seinfeld takes place in a parking deck at a shopping center when the foursome can't remember where they parked Kramer's car.

However, as Charlottesville continues its cityfication, we might be wise to warm up to these facts of urban life, as they appear to be popping up (in large construction-project years, anyway) like mushrooms.

In the last 36 years, UVA and the City of Charlottesville have added 11 new garages to the urban landscape, and there are two more massive UVA garages opening this year. Just last week, UVA's new $12 million, 554-space Culbreth Road Garage opened to serve employee and student parking permit holders during the day and nighttime events in and around Culbreth Theater. Later this year, UVA will unveil its 11th Street garage, a 1000-slot stack that can already be seen from West Main Street.

In addition, a slew of private developers are beginning to incorporate decks into projects, most notably the Grand Marc condo complex near the Corner, which opened last fall with 700 spaces for its residents. There's a mixed-use development proposed for Fifeville with a 928-space parking deck, and architect Bill Atwood's Waterhouse condo project on Water Street will feature a 50-plus space underground deck.

Meanwhile, developer Keith Woodard still seeks approval for a multi-story First & Main project on the Mall that includes a futuristic underground automated parking machine that would tuck away 180 cars.

Still, parking decks are routinely scorned. In 2002, angry Lewis Mountain Road neighbors, concerned about the impact of UVA's Emmet Street garage, dubbed it the "1,200-car monster." More recently, Fifeville neighbors and city planning commissioners expressed dismay about the planned Fifeville development, located at Roosevelt Brown Boulevard and Grove Street, even though the project is said to be by-right. Commissioner Genevieve Keller says she can't believe anyone would want to live in a place facing a massive parking garage.

Like them or not, as long as our dependence on the car continues, as long public transit fails to catch the majority of riders, and as long as folks insist on parking as close as possible to their destinations, the parking deck may be one of our most persistent urban structures.

Consider this: there are 128,000 registered vehicles in Charlottesville and Albemarle County (a bit shocking considering our population is 132,000), which require a minimum of a 1,000 acres of parking. Count one space for work, another to shop or dine, and we're talking 3,000 acres of surface parking. And that's not including traffic at UVA.

Globally, the numbers are even more mind-boggling. In 2000, 6.1 billion people on earth owned 735 million vehicles. At current ownership rates, and as more people in developing nations like China buy cars, there could be more than 4 billion cars on earth before the end of the century– which will require a parking lot the size of Spain.

"People don't appreciate these structures," says Bob Stroh, president of Charlottesville Parking Center Inc., which operates one of the crown jewels of local decks, the VMDO-designed Water Street Parking Garage. "But they're great land use," he continues. "Imagine having to pave ten blocks downtown to accommodate the vehicles that the Water Street and Market Street garages can."

Indeed, if Charlottesville's parking decks didn't exist, we'd have to find almost 80 acres of surface parking somewhere.

The nuts and bolts

"It's tough to design a truly exceptional parking garage," says VMDO architect Joe Celentano, who worked on the John Paul Jones Arena's 780-space structure and the Water Street deck. "Those that address their urban conditions are most successful."

For example, he says VMDO used the natural grade of the Arena site to work the great mass of the deck into the hillside, shielding much of it from view: only two floors are visible from Massie Road, and much of the deck is screened from Copeley Road and Emmet Street by woods. Embedding it in the slope also allowed creation of three entrances on different levels. In addition, a central heating and cooling plant for the arena, which also serves other buildings in the area, was built into the end of the deck.

As for the 1993 Water Street structure, Celentano says the same effort was made to match its design with its surroundings. In many ways– from the Water Street side, at least– the deck looks like just another building on the Mall, with its strong corner elements, a covered arcade and retail spaces, and its brick and soapstone skin.

However, the Market Street deck was truly ahead of the curve. Built in 1976, it has 450 spaces for the public and 50 reserved (for city police mostly), is nearly unrecognizable as a deck from a distance, and provides a seamless entry onto the Mall for pedestrians– not to mention a 360-degree view from the open top level and a glass elevator that's always been a favorite with kids.

A little history

Ironically, when automobiles began clogging urban streets in the 1930s, competing for curbside space with horse-drawn carriages, the first architectural instinct was to build "warehouses" to store them. In fact, early parking decks were often marvels of urban land use, employing complex elevator systems and fitting seamlessly into the landscape.

For example, in historic photos, the old Dupont Garage in Washington, D.C., which was built in 1906 in the 2000 block of M Street NW (it's long since demolished), looks like an upscale residence or office building; the Model Ts poking out the front entrances are the only hint that it's a garage. In 1928, the Kent Garage, a massive elevator-operated tower that could park 1,000 cars, opened in New York City.

In 1924, architect Frank Lloyd Wright even got in on the action, designing a spiraling parking deck for Sugarloaf Mountain in Maryland that included parking on the ramp itself. The deck was never built, but Wright's ramp idea eventually became the standard. In fact, many architectural historians believe Wright used this garage's spiraling ramp as a model when he designed the Guggenheim Museum, "parking" art instead of cars.

But automobiles became more than mere machines to Americans– they became symbols of freedom and mobility. We wanted to come and go as we pleased, and everyone from car manufacturers to shopping centers began catering to that desire. Along with cheap gas came free parking, acres of it. Thus, pay parking decks evolved into Wright's easy access-exit ramp design, but they were still forced to compete with oceans of mostly free surface and curbside parking.

Consider the expansion of Route 29 north, a temple of automobile worship. Witness U-Hall, the Arena's predecessor, built in 1965 surrounded by a sea of asphalt. And there's Vinegar Hill, a downtown neighborhood and row of storefronts demolished in the name of urban renewal. Except for the towering Omni hotel which hugs the Downtown Mall, Vinegar Hill was replaced with suburban idols: a big grocery store (now Staples), a pair of fast-fooderies including a McDonald's, a drive-thru bank, and a mini-mall– all with wide expanses of asphalt parking.

It appears that most of the land taken from the Vinegar Hill merchants and dwellers was converted to parking lots.

City planners talk a lot these days about Charlottesville's future as a more pedestrian-friendly urban center, but for decades we appear to have seen ourselves as fundamentally suburban. According to Celentano, however, it won't be new urbanists who'll reverse this dynamic, but something more elemental.

"I'm afraid it may just be the economic pressure induced by rising property values that eventually leads to parking decks," he says, "and possibly, to improved public transportation."

Decking UVA

At UVA, where the search for a parking space can be an epic quest, it appears the deck's time has come.

"There's been a shift toward higher-density parking and away from surface parking at the University," says parking administrator Rebecca White, "in an effort to use University land more efficiently and support compact growth."

White says there are close to 40,000 people on grounds every day, many of them with cars to park: as many as 2,000 a day at UVA Hospital decks. In addition to decks, White says, the University has stepped up efforts to discourage driving– as if waiting years for a parking permit weren't enough incentive to get to work some other way– by funding a program whereby employees and students can ride Charlottesville Transit buses by showing their ID, publishing a Bike Route map and installing bike racks (20 bike stalls have been built into the new 11th Street Garage).

UVA has even developed an "occasional parker permit"– allowing people who choose transportation alternatives to use the Emmet Street Garage and the new Culbreth Road Garage for special occasions.

Of course, more draconian measures have been in place for years, such as UVA's long-standing policy of banning cars for first-year students and making lots and decks closer to the University more expensive.

Meanwhile, White says, soon the Lee Street deck across from the Primary Care Center (known as the Hospital West Garage) will be demolished to make way for a new Cancer Center. Patient parking, she says, will be diverted to the deck across the street (the Hospital East Garage), and overflow patient and employee parking will be provided by the new 11th Street Garage.

And the City?

While, according to city spokesperson Ric Barrick there are no immediate plans to build municipal decks, the city nevertheless welcomes deck ideas from developers. Indeed, developer Oliver Kuttner once proposed that the city build a deck beneath the Water Street parking lots and sell or lease the air space above it to developers. However, as Barrick points out, the winner of last year's Water Street Design Competition that generated ideas for developing the two Water Street surface lots did not include a parking deck.

"Of course, that doesn't mean we won't have some interest from developers that would include a garage," Barrick says. "But, in general, we work on a regular basis to keep as many people out of cars as possible by using public transportation and building a pedestrian network through the city. Our hope as we redevelop downtown is that you'll have everything at your doorstep, and you don't need to drive to get services and goods."

Barrick's comments and the omission of a deck in the winning design, however, seem to reveal what Celentano calls a "long standing issue of cars versus people in the development of American cities.

"People like the convenience of driving, but with pressures from parking to traffic to sustainability, more cities are taking specific measures to limit the cars," he says. "Of course, improved public transportation will be helpful in achieving this, but I think a cultural change will be necessary before people start leaving their cars at home."

"It's a touchy subject," says Zachary Shahan, executive director of Alliance for Community choice in Transportation, "but part of promoting alternative transportation is not making it easy to park. Ubiquitous parking competes with other modes of transportation."

Unfortunately, until public transit improves substantially, such thinking seems to put business and government at odds. "There are no options right now," insists Stroh, who also heads the Downtown Business Association. "You drive downtown, or you don't come down at all."

Meanwhile, as vehicle ownership rates continue to rise along with urban land prices, we don't need a weatherman to see which way the wind blows. Anyone who has tried to find a parking space at Barracks Road Shopping Center during December has seen a glimpse of the future.

"We understand that parking is a concern," says John Tschiderer, VP of Development at Federal Realty, Barracks Road's management company. "And even though the number of parking spaces exceeds government standards, it's still being compromised."

Ironically, the Barracks lots are being compromised in part by the John Paul Jones Arena. Despite the Arena's own deck and surface parking (1,300 spaces in all), Barracks Road still gets flooded with cars during major events.

Last year, Tschiderer says, the shopping center added 31 extra spaces by re-striping the north lot, and he says they're looking for other ways to add spaces. But it appears the pressure to add a deck may be mounting.

"We want to avoid having angry customers who can't find parking," he says, "and so we're studying ways to include a structured parking deck. But for now were looking at ways to improve surface parking first, since it's more cost-effective."

The parking paradox

Building decks may be a more efficient use of pricey land and a smart solution for urban parking, but getting people to use them is another story.

As Stroh admits, "The Water Street parking garage is never filled, ever. It always has space; I've said I'd pay someone $100 if they couldn't find one."

Indeed, one of the paradoxes of the so-called "downtown parking problem" is that there may not be one. According to past city parking studies (and city traffic engineer Jeanie Alexander says her office is about to begin a new one), there's an abundance of parking close to downtown, just not as close as people may be accustomed to. In addition, many folks simply refuse to pay for deck parking.

"Some people, I think, have an expectation of free, convenient parking," says Barrick, "especially if you've grown up here. But when you go to places like D.C. or New York, you realize it's not really that bad. Part of it is growing pains, I think, as we go from being a small-sized city to a small mid-sized city."

Here's where the difficult cultural change Celentano alluded to comes in. Not only does alleviating the traffic at places like Barracks Road Shopping Center require people to start leaving their cars at home, but when they do drive, it might also require relinquishing the expectation of free parking.

As Yale economist and parking issue guru Donald Shoup points out in his book, The High Cost of Free Parking, studies show that driving around looking for free or low-cost curb spots accounts for about 30 percent of the traffic congestion in downtown areas. Indeed, virtually all day long, drivers on the Mall are doing what Stroh calls the "the two-hour shuffle."

"It's a game that's a huge problem," Stroh says, "people downtown moving their cars every two hours. It just doesn't work, doesn't free up space. Eventually, it's a problem the city will have to address."

"Drivers often compare parking at the curb to parking in a garage and decide that the price of garage parking is too high," Shoup wrote in a New York Times op-ed piece last year. "But the truth is that the price of curb parking is too low. Underpriced curb spaces are like rent-controlled apartments: hard to find, and– once you do– crazy to give up. This increases the time costs (and therefore the congestion and pollution costs) of cruising."

Shoup advocates charging market prices for parking in urban areas, not only as a way to discourage cruising, but as a way of coaxing drivers to use parking decks– and perhaps even convincing shoppers to leave cars at home.

However, Shoup also suggests that the habit of searching for free parking won't be an easy one to break (indeed, it's the reason most folks put up with the inconvenience of using Barracks Road when they go to JPJ events, are willing to do the "two-hour shuffle" downtown, and in general avoid parking decks altogether).

George Costanza illustrates the point.

"My father never paid for parking, my mother, my brother, nobody," says the Seinfeld character in one of his characteristic rants. "It's like going to a prostitute. Why should I pay when, if I apply myself, maybe I could get it for free?"

Meanwhile, our new decks beckon, and Stroh has a Benjamin for the last parker who arrives.

UVA's new $12 million,540-space Culbreth Road Garage opened at the end of February to serve employee and student parking permit-holders during the day and events at Culbreth Theater and locations on grounds after hours. PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

The Lee Street deck across from the Primary Care Center (known as the Hospital West Garage) will be demolished to make way for the new Emily Couric Cancer Center. Patient parking will be diverted to the deck across the street (the Hospital East Garage), and overflow patient and employee parking will be provided by the new 11th Street Garage.PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

Sticker shock or primal fear? Experts say downtown parking garages have always been curiously under-utilized. They blame the acres of free or low-cost curb parking. Why pay when you can get it for free– if you're lucky (or cruise long enough)? Others are more philosophical, suggesting that dark, unwelcoming caverns turn people away.PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

Ahead of its time? The Market Street garage has the distinction of not looking like a parking garage at all.PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

Big foot: The new 1,000-space 11th Street garage is hard to miss heading down West Main from the Corner: it has the scale of a stadium or a Roman archway.PHOTO BY DAVE MCNAIR

Building decks may be a more efficient use of pricey land and a smart solution for urban parking, but getting people to use them is another story. "The Water Street parking garage is never filled, ever," says Bob Stroh. "It always has space; I've said I'd pay someone $100 if they couldn't find one." FILE PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

Decks of the future

Volkswagen's Autostadt (car city) in Wolfsburg, Germany includes this 20-story robotic parking deck, which can hold 400 cars.

PHOTO FROM VOLKSWAGEN WEBSITE

While in recent years, architects designing parking decks have tried to make them blend into the urban landscape, a few have tried to make them beautiful.

Moore Ruble Yudell Architects & Planners (the same folks designing UVA's South Lawn project) recently completed a solar-powered parking garage in Santa Monica with multi-colored glass façades to admit natural light and that includes a café and a Zen Garden. (see photo).

Over in Staunton, the award-winning New Street parking garage mimics a classic railway station, not only blending into the downtown area, but also adding to its architectural flair.

In the future, however, the trend may be toward making them disappear altogether.

"The latest trend we're seeing is automated parking systems," says VMDO architect Joe Celentano. "They've been used in Europe, and a few have been completed in this country recently.

"Basically, the cars are stored in a simple structure (more like a vault) and manipulated by some type of automated equipment. It saves space. You can pack the cars in because there is no public circulation space– it works like valet parking. You don't have to experience the parking garage itself. It's still on the expensive side, but it's becoming more affordable all the time."

Indeed, if local developers Keith Woodard has his way, we might see one right here in Charlottesville. When Woodard first proposed his First & Main project, a 9-story mixed-use building on the Downtown Mall, it included an automated underground parking system.

"Basically, it's a car elevator that stacks cars underground," Woodard's project architect told the Planning Commission. "You drive your car into the elevator, and when you get it back, it's turned around."

"We investigated using that system when we were in the planning process," says Woodard. "But we put the project on hold for a variety of reasons, primarily uncertainty with zoning issues."

Indeed, the city balked at the size of Woodard's building, and the Board of Architectural review didn't like the fact that Woodard wanted to demolish the existing buildings to make way for the underground parking structure.

Moore Ruble Yudell Architects & Planners recently completed a solar-powered parking garage in Santa Monica with multi-colored glass facades to admit natural light and that includes a café and a Zen Garden.

PHOTO FROM Moore Ruble Yudell Architects website

Staunton's New Street parking garage

PHOTO COURTESY FRAIZER AND ASSOCIATES

Fast facts: Charlottesville garages in brief

by Laura Burns

By the numbers:

Largest garage: UVA hospital South garage, approximately 1338 spaces

Smallest garage: Elliewood deck, 41 spaces

Oldest garage: Nursing school garage, built in 1972

Most Expensive garage: 11th Street Garage, estimated at $35 million

Existing garage parking spaces: 9,828

Planned garage parking spaces: 2,135

Fun fact: If all the garages in Charlottesville were made into a giant parking lot, it would cover almost 80 acres.

Garage by garage lowdown

UVA decks:

Central Grounds garage

Year built: 1994

Number of spaces: around 400

Architect: Walker Parking Consultants with Mariani and Associates

Use: Open to the public as well as Wahoos

Buzz: Has the UVA Bookstore on top. Part of the $10 game-day system.

Emmet/Ivy garage

Year built: 2003

Number of spaces: around 1,200

Use: UVA students and employees who have purchased a permit for the academic year for $16-$36/month plus game days.

John Paul Jones Arena garage

Year built: 2006

Number of spaces: about 780

Architect: VMDO

Use: Open weekdays for UVA employees and students as a commuter lot, it often fills during Arena events.

Cost: Fee varies by event.

Darden School garage

Year built: 2003

Number of spaces: 500

Cost: $58/month, UVA permits

Hospital East garage

Year built: 1986

Number of spaces: 830

Architect: Davis, Brody & Associates

Use: Used by patients, visitors, and employees of UVA hospital.

Cost: Patients and visitors can Use the garage free with validation to avoid the $4/hour price.

Hospital South garage

Year built: 1993

Number of spaces: 1,388

Architect: Tobey & Davis

Buzz: The public can buy a season pass for parking on game days.

Hospital West garage

Year Built: 1979

Number of spaces: 321

Architect: Johnson, Craven & Gibson

Use: Open 24 hours/day, 7 days/week.

Buzzkill: It's slated for demolition.

Hospital nursing school garage

Year built: 1972

Number of spaces: around 140

Use: $70/month, UVA permits

Buzz: This is the oldest garage in town.

Scott Stadium garage

Year built: 2000

Number of spaces: around 450

Architect: Martin-Horn

Use: Part of the $100 million renovation of Scott Stadium, it serves employee and student permit holders on weekdays.

Buzz: On football game days, it's loaded with big donors and box-holders.

11th street garage

Year built: 2008 (almost finished)

Number of spaces: around 1,000

Buzz: This is that biggie you've seen looming over Main Street, soon to open for patients, visitors, and employees of UVA hospital– who can get free validation.

Culbreth Road garage

Year built: 2008 (opened last week)

Number of spaces: 554

Buzz: Its placement in a ravine between the railroad tracks and Culbreth Road lets the land mask the structure's bulk.

City Decks:

Market Street deck

Year Built: 1976

Number of spaces: 500

Management: Charlottesville Parking Company

Cost to park: $2/hour, $16/day maximum, $130/month

Use: Open to the public

Buzz: It has a glass elevator and a monthly waiting list.

Juvenile & Domestic Relations Court deck

Year approved: 2005

Planned number of spaces: 89

Buzz: Still in the planning stages, this one has been slowed by the 2006 collapse of a corner of the building it was supposed to serve.

Private Decks:

Water Street garage

Year built: 1993, addition added in 2000

Number of spaces: initially 692, currently 1,019

Architect: VMDO

Management: Charlottesville Parking Center

Cost to park: $1.50/hour, $12/day ($7.50 early bird special if you arrive before 9am), $115/month.

Buzz: The 2000 addition along the train tracks won a design award.

Elliewood deck

Year built: c. 1985

Number of spaces: around 40

Management: Piedmont Virginia Parking Company

Buzz: Not cheap: $2/hour, $200/month.

14th street garage

Year built: c. 1985

Number of spaces: 217

Architect: Richard Shank, of Shank & Gray

Management: Piedmont Virginia Parking Garage

Buzz: Today's toll-takers are tomorrow's rock stars.

Omni hotel deck

Year built: 1985

Number of spaces: 217

Buzz: Open for hotel and public use.

Lexis Nexis deck

Year Built: 1992

Number of spaces: about 400

Buzz: Free parking for Lexis Nexis employees on just two mammoth levels

Martha Jefferson deck

Year Built: early 1991

Number of spaces: five levels, 220

Buzz: Free parking for visitors and staff. It's gonna serve something other than Martha Jeff by 2012.

ACAC deck

Year built: 2006

Number of spaces: 192

Buzz: $1/hour, but members and club guests receive 2.5 hours free.

Grand Marc deck

Year built: 2007

Number of spaces: 700

Architect: BJO

Buzz: Biggest condo deck in town; $85/month for residents.

King and Grove Street deck

Project approved: December 2007

Proposed number of spaces: 928

Architect: Mitchell/Matthews Architects and Urban Planners

Management: Grove Street Properties LLC

Buzzkill: So massive it's causing some consternation in the Fifeville community.

Gleason Project garage

Project approved: 2007

Proposed number of spaces: 118

Architect: Daggett & Grigg

Buzz: The project will include office space, sub-street level retail, and condos.

#