MOVIE REVIEW- Choice v. life: Two films let you be the decider

If you don't believe in coincidence, blame harmonic convergence for two films about abortion showing up around the same time, both of which are as serious as Juno and Knocked Up, in which pregnant women chose not to abort, were funny.

If you don't believe in coincidence, blame harmonic convergence for two films about abortion showing up around the same time, both of which are as serious as Juno and Knocked Up, in which pregnant women chose not to abort, were funny.

Tony Kaye's documentary Lake of Fire shows Sunday night in UVA's Offscreen series. The Romanian drama 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days is opening soon at the Vinegar Hill Theatre. Both were overlooked, some say unfairly, this year for Oscar nominations.

As a general rule, documentaries of 90 minutes or less are for people interested in the subject. Up to two hours they're for people passionate about the subject, and beyond that they're for people obsessed with the subject.

Lake of Fire runs two-and-a-half hours so it's for people obsessed with the fundamentalist Christian view of abortion. Which side is it on? That depends on which side you're on. Pro-lifers, who must do over 75 percent of the talking in the film, should feel they've been given a good platform to express their views, while the pro-choice crowd will conclude the others have been given enough rope to hang themselves.

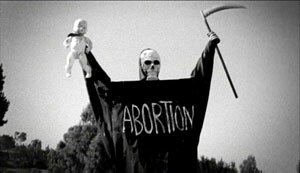

The filmmaker, whose American History X was controversial for its content and the director's fights with the star and studio, shot Lake of Fire in black and white but ultimately shows the abortion question is less black-and-white than people on either side will admit– which is what hinders constructive dialogue.

Attorney Alan Dershowitz says everybody is right on both sides, although he chooses choice. So does Noam Chomsky; but jazz critic Nat Hentoff, an atheist, is pro-life.

Being pro-choice, I see the pro-lifers as only respecting the life of a fetus. Once it's born, it's subject to their views in support of war and capital punishment and opposing gun control and welfare. The most outspoken pro-lifers describe murderers of abortion doctors as heroes. At least one advocates the death penalty for "sodomites" and "blasphemers," the latter including anyone who says "God damn." His gosh darn views are more extreme than some.

Much of Kaye's footage was shot in the '90s, including a 1993 pro-life demonstration in Washington and murder trial in Pensacola for the shooting of an abortion doctor. Paul Hill, years before his execution for two other Pensacola murders, is shown declaring, "Murderers should be executed, and abortionists are murderers."

Although he's not interviewed for the film, there's coverage of Eric Rudolph, who ultimately confessed to bombing two abortion clinics, a lesbian bar, and the 1996 Olympics.

Among many subjects is Norma McCorvey, Roe of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion in the U.S. She relates how she was later converted by pro-life Operation Rescue, which set up shop next-door to the abortion clinic she was working in.

Not everyone is identified, including the wackjob who states, "In California, they have ‘Lift Up Your Dress Week' in sixth grade, where children have to choose between homosexuality and heterosexuality." (I guess the boys who lift up their dresses are homos.) One woman declares the last three doctors she worked for were murdered. I wouldn't mention this to prospective employers.

More troublesome, considering that Kaye worked on the film for 15 years or more, is that many clips aren't dated. How current, for instance, are the alleged statistics about the declining numbers of doctors willing to perform abortions and medical students learning the procedure? Alan Keyes and Pat Buchanan are identified as Republican Presidential candidates, which might be disconcerting to John McCain.

Toward the end, a 28-year-old woman is followed at an abortion clinic, from counseling through the actual procedure and breaking down afterwards, although what she's feeling as she leaves is up to the viewer to intuit.

It may come down to who you think the martyrs are– the doctors killed for terminating pregnancies, the pro-lifers who terminate the doctors and pay with their freedom, or the unborn infant whose body parts we see on a tray after being removed from its mother.

The winner of last year's Palme d'Or at Cannes, 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days would seem like a mystery if you went in without knowing what it's about. In Romania in 1987 two college roommates, Otilia (Anamaria Marinca) and Gabita (Laura Vasiliu) are getting ready for something. It's not clear what, but it's obvious that the nervous Gabita is putting all the responsibility off on Otilia, a natural take-charge type.

The few details Gabita was supposed to take care of have been mishandled, and Otilia is left to sort them out. To make matters worse, Otilia's boyfriend is pressuring her to attend a birthday dinner for his mother that evening.

It's eventually revealed that Gabita is getting an abortion. While that may be the emotional core of the film, it's really a broader look at life under communism, which was soon to end in Romania. Details large and small show the deprivation people lived with, the difficulty of dealing with bureaucracy, and the ready availability of everything from breath mints to abortions– for a price– on the black market.

A generation has grown up in Romania since the fall of communism in 1989. Cristian Mungiu, this film's writer-producer-director was born a generation earlier, in 1968, so he knows both sides.

You can argue about whether 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days is pro-life (you won't see an aborted fetus in Planned Parenthood ads) or pro-choice (if abortion is legal, women aren't subject to the risks and other negatives they suffer in this film to obtain one). Either way, it's definitely anti-communist.

Vlad Ivanov plays Mr. Bebe, the abortionist, a genuinely scary man. He's very finicky about how things should be done, largely for his own protection, and it's surprising how he expects to be paid. Gabita complicates things by not getting a room in one of his favored hotels, where they're better about looking the other way, and by lying about being in her first trimester when she's actually– well, check the title.

Mungiu works in long takes, often with a static camera. Whether that's for artistic or budgetary reasons, it puts a strain on the actors, who come through with flying colors. Marinca is amazing at the dinner table scene, where her silence says more than all the conversation flowing around her.

Both these fine films offer food for thought for all sides, if they'll only stop and think.

#