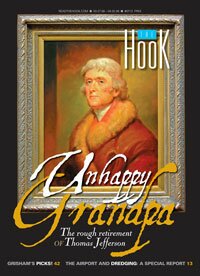

COVER- Unhappy grandpa: the rough retirement of Thomas Jefferson

It was March of 1809 when the third president, then 65 years old, was leaving Washington. "Within two or three days," he wrote, "I retire from scenes of difficulty, anxiety & of contending passions to the elysium of domestic affections & the irresponsible direction of my own affairs."

Yet for the Sage of Monticello, peace at his mountaintop home would be shattered by incapacitating disease, financial ruin, and domestic violence that literally brought him to his knees.

A stunning revision of the popular modern image of Jefferson's retirement is the subject of Twilight at Monticello: The Final Years of Thomas Jefferson, a new book by Alan Pell Crawford.

***

Certainly, the traditional image of Jefferson's last 17 years at Monticello is of a doting family patriarch, amazingly healthy for a man his age, surrounded by adoring and well-behaved progeny, indulging his scientific interests, tweaking his favorite vegetables, and fixed on the hobby of his old age: the University of Virginia.

"But," says Crawford, "it's a more interesting place if you know the things I know."

By the time the next president, James Madison, was inaugurated, ex-President Jefferson had packed his personal papers and effects, several wagon loads from the President's House, and settled the $11,000 debt he had incurred in his eight years as chief executive.

On March 6, happy to have escaped the burdens of public office, Jefferson was writing "as a private individual" to John Armstrong, the American minister to France, that never again would he suffer from "difficulty, anxiety" or from "contending passions."

The tranquil modern impression of Jefferson's retirement has been created by many well-meaning sources. Because of his many-faceted life– his over 30 years in office, his wide-ranging interests, his amazing accomplishments– the public has been fed a steady diet of "topical" Jeffersonian books and articles, most written with a very narrow focus.

Hundreds of books and essays bear titles like "Jefferson and the American West," "Thomas Jefferson: Architect," "The Wines of Monticello," "Jefferson the Gourmand," or "Deism and the Declaration." (I should know, as I've written close to 20 such articles.)

Very rarely have we seen a straight narrative of his life, or a part of it, wherein all of his life's various elements are explored. Enter Allen Crawford.

A former U.S. Senate speechwriter, Congressional press secretary, and magazine editor, Crawford, who lives in Richmond, has written about politics and history for many top newspapers, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, and The Wall Street Journal. In his previous book– Unwise Passions: A True Story of a Remarkable Woman and the First Great Scandal of Eighteenth-Century America– published in 2000 by Simon & Schuster, Crawford tells the tale of a young Virginia belle, Nancy Randolph, who in 1793 was accused, along with her brother-in-law, Richard Randolph, of killing her newborn infant. But there was much more to this salacious story: Richard Randolph might have been the child's father.

"In researching Unwise Passions," Crawford says, "I learned a fair amount about the Randolph and Jefferson families. I remember being struck by Nancy Randolph's description of Monticello (recorded during a visit in the 1790s, I believe) as dusty and noisy, a construction site."

That account was such a contrast to the typical image of the stately plantation that Crawford pressed forward to learn more "about life as it was really lived" at Monticello.

While he was here in Charlottesville, as a fellow at the International Center for Jefferson Studies, for example, Crawford researched Jefferson's proposal for "ward republics"– small state-government entities that would help the American people retain more of the power of government. The book focuses on the years from 1809 to 1826 and includes a small section on Jefferson's "wards."

In Twilight at Monticello, Crawford proves that he has learned plenty about the autumn of Jefferson's life. He chronicles that period in detail both delightful and disheartening.

Here we see the familiar, successful Jefferson– the loving family man, the founder of the University of Virginia– juxtaposed with the perhaps unfamiliar afflicted and long-suffering retired statesman, a man beset by family scandal and tragedy, and overwhelming, calamitous debt. Ironically, Jefferson's indebtedness was so deep that he reversed his long-held opposition to lotteries to ask the General Assembly to let him hold a lottery– for himself.

Fast-paced and engagingly written, Twilight at Monticello delivers Thomas Jefferson warts and all. Or should one say "boils" and all?

Writing about Jefferson's 1818 visit to Hot Springs, a Bath County health spa, Crawford notes that the 75-year-old found the experience "delicious" and soaked in the foul-smelling 98-degree water three times a day. During the second week, however, a "large swelling" appeared on one of his buttocks, apparently the result of an infection. The swelling had increased "for several days past in size and hardness," he told [daughter] Martha Randolph, preventing him from "sitting but on the corner of a chair."

***

While Jefferson's retirement began in 1809 when he left Washington, Twilight opens with a day-in-the-life: February 1, 1819. It's chock-full of gardening details ("Jefferson would inspect with boyish glee the condition of the vegetables and medicinal herbs that grew, pale green to a ghostly gray, in winter"), and information about his reading habits ("Jefferson was once again losing himself in Thucydides' account of the Peloponnesian War– in Greek, of course.")

After 14 pages, this prologue finally reveals its purpose: February 1, 1819 was the day Jefferson learned that near Court Square in Charlottesville his first granddaughter's husband, Charles Lewis Bankhead, had assaulted and stabbed his favorite grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph. It was the first of many such shocking and outrageous incidents perpetuated by Bankhead, a hard-drinking brute.

Crawford next presents us with a 50-page rendition of Jefferson's life up to and including his two-term presidency. Of his mother, Jane Randolph, we learn that Jefferson "never seems to have spoken fondly of her even to his own children."

And we discover the uneven distribution of intellect among the siblings of the Jefferson clan. Crawford relates a conversation between Jefferson and his younger brother Randolph about a typical farming dilemma.

"'Tom, I'll tell you how to keep the squirrels from pillaging the corn," Randolph Jefferson supposedly said. "You see they always eat on the outside row. Well, then, don't plant any outside row."

This section of the book will be familiar fare for even a beginning student of Virginia history. Jefferson grows up on the Virginia frontier, receives the best Virginia education possible at William and Mary in colonial Williamsburg, is elected to the House of Burgesses, and marries well-to-do widow Martha Wayles Skelton (thereby more than doubling his wealth in lands and slaves).

With the outbreak of war, Jefferson becomes famous for his authorship of the Declaration of Independence then serves two years as governor of the Old Dominion– a post that ends, rather tragically, with him fleeing Monticello at the approach of British dragoons. With peace come Jefferson's five years as minister to France– 1784-1789– followed quickly by service as our nation's first secretary of state (under President George Washington), second vice president (in the John Adams administration), and third president.

This is the book's thesis, a notion nicely summed up in the opening quote by Sébastien-Roch Nicholas Chamfort, a French contemporary of Jefferson's: "Nature intended illusions for the wise as well as for fools lest the wise should be rendered too miserable by their wisdom."

Crawford writes that from his earliest education, "Jefferson was an idealist, though he never thought of himself as such. Seeing himself as a scientist... Jefferson was firmly convinced that he based his conclusions on observable phenomena... Jefferson's view of himself as an empiricist may also suggest how little self-knowledge he possessed, for the struggle between the life of the mind and the hard facts of material reality would form the tragic drama of his life."

During his 17-year retirement, hard facts came at Jefferson fast and furious.

First were his mounting physical ailments. Jefferson, we need to remember, lived into his early 80s– and died at 83– probably a good 25 years beyond what an average American of his day could expect.

Aside from boils, he was hounded by a broken wrist he suffered many years earlier in Paris while cavorting along the Seine with Maria Cosway, a married woman with whom he "carried on an intense, though perhaps unconsummated, love affair," Crawford says. He was afflicted with rheumatism– his feet and hands so swollen at times that he was barely able to walk– as well as severe constipation, a "cholic which was attended with a stricture of the upper bowels" (as Jefferson related to Madison in 1818). Add to these prostate and bladder difficulties that made urination extremely painful, and it's easy to understand why Jefferson relied on opiates– both opium and laudanum prescribed by his physician– to ease his suffering.

Then there was his steadily mounting debt.

Born into the gentry, and with extravagant tastes in just about everything, Jefferson simply could not rein in his spending (especially after leaving the presidency and its $25,000 salary). He bought lavish gifts for his descendants and built another expensive home, Poplar Forest in Bedford County, all the while borrowing heavily because his crops were not bringing in enough cash.

"He now realized," writes Crawford, "that despite his interest in the theoretical aspects of agriculture, he was ‘an unskilled manager of my farms,' and it was time to turn to someone who might handle things better."

In his meticulous manner, however, Jefferson kept incredibly detailed account books. "His record keeping," writes Crawford, "seems to have performed a primarily psychological function rather than a functional one. These minute entries, one following another, day after day, month after month, year after year, accumulating over a lifetime... gave Jefferson the feeling that he exercised more control than he did...."

Sadly, when he died, he was $107,000 in debt– a total that in today's money would be several millions of dollars.

As for the violent Bankhead, he caused never-ending sorrow and desperation at Monticello. He drank, gambled, got into fist fights, and– more distressing to the Jefferson and Randolph families– beat his young wife, Jefferson's beloved granddaughter, Anne Cary Randolph.

When she died in 1826 at the age of 35 (not due to a beating), the 82-year-old Jefferson was led into her room where, according to Dr. Robley Dunglison, "he abandoned himself to every evidence of intense grief."

***

The early University of Virginia students were another a source of grief for Jefferson in his final days. One of his finest accomplishments– and certainly his greatest gift to his county– the University opened for business in 1825, the year before his death.

The first students were the proud and well-heeled sons of plantation owners– youngsters who brought their guns, horses, and body servants to Charlottesville's "academical village." Within a short time "nightly disorders" broke out. Fueled by strong drink, the students broke windows on the Lawn, "cursed the foreign-born faculty members," and even attacked two professors with brickbats.

Infuriated by their behavior, Jefferson attended an assembly in the Rotunda at which the faculty hoped to identify the student ringleaders.

"The students filed in," writes Crawford, "and among those suspected of having assaulted their professors sat the nephew of one of Jefferson's own grandchildren. Jefferson rose to address the students, but... he recognized this young face in the crowd and was too overcome to go on."

In Twilight, Crawford reveals Jefferson's tendency to shy away from painful realities, such as his own greatest contradiction– that the man who wrote in the Declaration of Independence that "all men are created equal" was himself a slaveholder.

When Albemarle native Edward Coles announced his desire to free his slaves and take them out of Virginia, Jefferson expressed the wish that "your success may be speedy and complete." In typical paternalistic fashion, however, he warned Coles that black people were "as incapable as children of taking care of themselves," and reminded him that it was his duty to "feed them and clothe them well, [and] protect them from ill usage." Upon his death, Jefferson freed only five of his own slaves– all of them from Sally Hemings' family.

Through it all, Jefferson maintained an upbeat and positive attitude. Following the UVA disturbances, for example, he wrote that the institution had in fact gained "from what appeared at first to threaten its foundation."

What was the source of Jefferson's inner strength? According to Crawford, it was his unflinching belief in the tenets of the prevailing philosophy (a belief that proved to be both fortifying and debilitating).

"Jefferson thoroughly accepted the ideas of the Enlightenment," Crawford says, "that man is above all a rational creature, fully capable of managing his life through the application of Reason. This view of life simply refuses to acknowledge the existence or reality of human evil– of depravity."

The attitude would help explain Jefferson's silence when word got back to him that two nephews had taken part in the murder and dismemberment of a slave. Crawford concedes that Jefferson's optimism had become "a kind of self-deception."

The book, however, contains some factual errors that might raise some eyebrows such as placing the town of Milton "west" of Monticello, when it actually lies to the east.

More serious are mistakes in a chapter entitled "The ‘Yellow Children' of the Mountaintop."

Here Crawford stretches the truth in his effort to prove that Sally Hemings could slip into Jefferson's bed chamber undetected. During one period of reconstruction and alteration at Monticello– there were many– porticles, or Venetian porches, were attached to the outside of his library (and the library, as every visitor to Monticello knows, is connected to his bedroom).

"Around the time that Jefferson installed the porticles," Crawford writes, "he added one further access to his bedroom. This was a circular staircase that led directly into Jefferson's library from the slave quarters under the terrace where Sally's ‘servant's room' was located."

But the Venetian porches and the staircase were constructed at two very different times– 1805 and 1796 respectively– and the staircase leads into a hallway, not directly into Jefferson's library. These two sentences are "very misleading," according to Cinder Stanton, Monticello's senior research historian.

"I still think that he fathered children by Sally Hemings," Crawford nevertheless maintains, "but that's because the alibis are so weak."

The chapter on Jefferson's passing contains a few more errors. Crawford lists John Adams's age, at death, as 91 (he was 90). More alarmingly, Crawford misstates Jefferson's time of death as "ten minutes to twelve." He died one hour later at 12:50pm.

Despite these problems, Twilight at Monticello is a wonderful addition to the Jefferson bookshelf. Readers will find Crawford's book to be enjoyable and easy to read, a much shorter successor to the last great treatment of Jefferson's retirement years– Dumas Malone's The Sage of Monticello, published in 1981.

In Crawford's pages readers discover Jefferson's turbulent twilight, the years when he seemingly refused to acknowledge the chaos swirling around him. "Of course if he had," says the author, "he would not have been able to accomplish the things he did."

Rick Britton is a Charlottesville-based writer and cartographer. He is editor of The Magazine of Albemarle County History and author of the soon-to-be-released Jefferson: A Monticello Sampler.

#

12 comments

Rick,

A very good read on Alan Crawford's book, Twilight at Monticello. I am a Jefferson Family Historian who assisted Dr. E.A. Foster with the Jefferson-Hemings DNA Study. Even though Mr. Crawford's book is about "the twilight years" he contributes 10 pages to "The Yellow Children" that you mention containing some errors. Even Cinder Stanton brands his remarks as "very misleading." Neither you or Cinder caught another VERY glaring error. He mistakenly writes that Randolph (TJ's brother), may have come to Monticello in the fall of 1808. In truth, TJ invited brother, Randolph, to Monticello in August 1807, EXACTLY 9 months prior to the birth of Eston Hemings. Why this drastic error when this time is critical to the reader in evaluating where Randolph possibly was at the time of Eston's conception?

Mr. Crawford carefully avoids telling his reader about the 13 top rated scholars one year research project, The Scholars Commission Report (www.tjheritage), which found fault with the Monticello Study and found NO proof that Thomas Jefferson fathered ANY slave child.

Since he performed much of his study at Monticello, why didn't he tell the reader that their study was chaired by an African-American oral history specialist and "swept under the rug" a Minority Report written by a trusted and faithful Monticello long time employee guide, Dr. Ken Wallenborn? Why did Dr. Dan Jordan then apologize for this unprofessional deniel of "both sides of the story" to the public? How about that statement that possibly not only one Sally child but possibly ALL of her children were fathered by Mr. Jefferson. What kind of careful research is this......ONLY ONE was tested and Dr. Jordan REFUSES to suggest to the Hemings that another valuable source of William Hemings (son of Madison), be secured from a grave in Leavenworth, Kansas.

My continuing research has shown that Dr. Foster should have informed Nature, the media, Monticello and the public that in all probability a match would occur, BECAUSE John Weeks Jefferson (Eston Hemings descendant), and his family back to Eston himself, had ALWAYS claimed descent from "a Jefferson uncle", a reference to Randolph, TJ's brother, thus the Jefferson DNA carrier. Eston or his family NEVER claimed descent from Thomas Jefferson.

Another lie was perpetuated upon the public when Samuel Wetmore wrote the Madison Hemings article in the Pike County newspaper (which was a prominent "research" document used by the Monticello Research Group). My own research reveals that Dolley Madison NEVER visited Monticello at Madison's birth at Monticello on January 19, 1805, as he claims. The Madison Papers indicate that the Madisons NEVER traveled to Virginia from Washington during winter. He even "bad mouths" Dolley by stating that she never kept her promise to give his mother a promised gift, but that was the way with white people.

Any one following the lives of these early founders would know that Dolley served not only her husband, James Madison, in his valuable job as Secretary of State but that she was a very valuable asset to Mr. Jefferson, serving as his White House Hostess, and January (after his re-election to a second term), was a VERY busy time. Let us "try" to emagine that she would announce to these very busy gentlemen that she must apologize for rushing off at this very busy time to attend the birth of a MALE slave at Monticello for whom she must name in honor of her husband. Never mind that this was three or four days of travel over frozen land and across frozen rivers without their companship. Next we must wonder........since this was well many years before the sex of a child could be determined, what if the child were to be a female???

As mentioned above you can see how a little deep research can produce much different results from politicall correct attempts to revise our country's great history. I call upon Monticello to REEVALUATE their research and let us form a joint research group composed of not only Monticello personnel but researchers from The Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society. Dr. Jordan and Ms. Cinder Stanton, will you accept this challenge?

Herbert Barger

Jefferson Family Historian

www.angelfire.com/va/TJTruth

Asst. to Dr. Foster on DNA Study

301-292-2739

I know everyone in this town loves TJ. Check out this re-enactment of likely conversation between Sally Hemmings and our main man Tom.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FkMi_s79z5k

I have to laugh at the revisionist "historian" Mr. Barger. Far too long have I watched the misinformed, sometimes racist, denials. I and others just find the perpetual proselytizing laughable. It's the simple things too. I find it hard to take any self-proclaimed scholar seriously when they are unable to post comments without spelling errors. Dan Jordan and Cinder Stanton have forgotten more about Jefferson than most of us, Barger included, will ever know. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation is to be applauded for its forthright and scholarly stance on the scientific evidence on this issue. The Foundation has done more to preserve the Jeffersonian legacy than Barger or Gene Foster ever will.

Most people-public, are fed up with the one-sided approach the TJ Foundation takes. The modern day Monticello folks don't know for sure and will most probably never know for sure, whether or not TJ was the father of Sally's child-children. Many I know, do not want to take their families to visit Monticello anymore, because of all the TJ bashing the Foundation supports. Show some respect. Everyone knows Sally's man COULD HAVE BEEN someone other than TJ. Unless someone comes up with real conclusive or more complete scientific evidence, allow TJ to rest in peace! If I were in charge of finances at Monticello, I would be concerned that some folks don't want to visit anymore, because they are OFFENDED. Tone it down TJ Foundation, until you know for sure!

That's true, Janie. But the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has NEVER, to the best of my knowledge, said that they have known for sure. This study was 10 years ago now and TJF hasn't taken a postion per se. They present the evidence and offer the best interpretation available. If you ask a guide about the alternate theories (and I have), I bet they would actually (imagine this) discuss it with you!

I just looked at their website, and The Foundation pledged in 1998 to "follow the truth wherever it may lead". It seems to me they are doing that. This is such a minute part ofwhy not visit and learn more about the *rest* of the Jeffersonian legacy? I doubt they will miss any of our admission fees.

Peter, The Foundation take "one side", and everyone knows this. There is just as much to argue-defend on the other side. As far as I have read, the other side makes perfect sense too. The Foundation does not equally balance the opinion in presentation. Sure, the Foundation allows discussion. They are welcoming, in a way-BUT Everyone knows they have "made up" their mind in one direction, and thats it!

TJ can't speak for himself anymore. The Foundation hasn't solved the crime conclusively or convincingly. How about innocent until PROVEN guilty? It looks bad for the Monticello Foundation itself, to talk trash about the very person that made the Foundation possible.

The "held position" is backfiring, in a concerning manner.

An insider mentioned to me, visitation has been down-recent years, because of the finger pointing-bashing of Jefferson. Monticello has cast such a bad light on our third President. There is an impact whereby visitors feel uncomfortable. Who wants to bring the kid to visit and then face the discussion with the kid on the way home: "Daddy, what did TJ do to Sally"?

No one has proven Jefferson himself did it. It is inappropriate and hurtful for the Foundation to assume/embrace this view.

Peter

"Follow the truth wherever it may lead"???

Seems the evidence does not lead far enough to (the one side), Monticello claims is the case.

Monticello couldn't talk or write about the living the way they do Jefferson. They would be sued.

This is slander and libel unto the grave.

Shameful too

Come on, TJ Foundation, this is too much.......Give us some HOPE!

Has anyone here, other than Mr. Barger (who has long consecrated his life to protecting the reputation of Thomas Jefferson), read the report issued by the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation (you can access it in full online at monticello.org), or consulted the comprehensive and erudite scholarship presented by the National Genealogical Society, the premier genealogical organization in the world, which conducted its own independent study of l'affair Hemings-Jefferson in its quarterly?

My question to Barger: Yes, Jefferson invited Brother Randolph to visit, and did Randolph Jefferson indeed visit during that time? I can't recall, but then Randolph Jefferson's Monticello visitation record is covered in the TJMF report at Monticello.org.

The report also covers the FACT that TJ was ALWAYS present when Sally Hemings conceived her children; conversely, Randolph and the other dozen Jeffersonians the scholars put forth as the father of the "yellow children of Monticello" were not, as they managed plantations of their own and had their own servants to do with as they wished.

You have to ask yourself: So every other Jefferson male of a certain age and reputation, etc., can be considered, but not the main man himself.

Why not?

Janie's opinion expressed as fact that visitation at Monticello is down because of all the Jefferson bashing in the official portrait is specious -- unless she can come up with data figures to support her view. I am sure Monticello keeps track of the exact numbers.

That said, I read the book in question and found Pell-Crawford's account of the Randolph scandal a better read for a variety of reasons best saved for another thread.

We'll never truly know the exact dynamic of the sanctum sanctorum of the man who drafted our Declaration, but then owned 200 slaves at the time of the signing, and who never denied himself anything to the extent that several subsequent generations of his cherished family were still drowning in his debts long after Thomas Jefferson left this mortal coil.

I highly recommend E.M. Halliday's "Understanding Thomas Jefferson" and McLaughlin's "Jefferson and Monticello" for beautifully-written, well-researched Jefferson biography.

For Hemings coverage: please do read the materials on the Monticello website, and then also the NGS Quarterly, vol. 89, No. 3, September 2001. The experts at the NGS offer their own investigation into the scholar's report mentioned by Mr. Barger and it's all very fine work, which I think everyone who is interested in this subject will enjoy reading.

Respectfully,

Jill Sim

Putative Hemings Descendant

Former Resident, Albemarle County

Jill Sim, Putative Hemings Descendant:

At the moment I am not familiar with your lineage or just which of Sally's children you may descend from, however, a couple of questions. FIRST: If you descend from Madison, WHY does your family REFUSE to DNA test William, son of Madison (possibly his DNA will contain the Carr DNA) and NOT Jefferson DNA. Only one Hemings was tested so the Carrs are STILL on the hook for further research. Without this DNA there is NO DNA proof that Madison and Eston had the same father. Madison maintains in the Pike Co. newspaper article that he was named at his birth by Dolley Madison while at Monticello.....an absolute MISSTATEMENT, the Madisons NEVER visited Va. from Washington during winter. So if this one false statement was made, just how many more of hias statements are suspect.........MANY in my opinion. YET, this article was one of few documents used for Monticello research.

SECOND: If you descend from Eston, as John Weeks Jefferson does (tested subject for Eston), are you not aware that Eston NEVER claimed descent from Thomas BUT "A Jefferson uncle or nephew." This is translated to mean Randolph Jefferson, TJ's younger brother, as known by that name by TJ's grandchildren and their slave playmates. When Dr. Foster was testing John Weeks Jefferson, I reminded him that if their claim were true that Nature MUST be so informed because there would be a Jefferson DNA match. He refused my suggestion to notify Nature until after the Nov. 5, 1998 issue was world wide run with a false headline. Due to pressure from me and others, Nature ran another clarifying article in the Jan. 7, 1999 issue confirming that the title and Dr Foster's analysis was misleading and WRONG.

As for the National Genealogical Society "special issue" please be advised that Mrs Mills, NGS Editor, was INVITED to be a member of the Scholars Commission (www.tjheritage.org) but REFUSED.....too busy. These people, although most professional in their chosen profession, were NOT proficient in the handling of this DNA project and their ASSUMPTIONS add little to the discussion.

In summary: The public is being "CONNED" for very obvious reasons, namely TJ owned slaves, thus didn't all slave owners act in this manner. Save this for soap operas and leave our children's textbooks free from such unproven remarks by so called "authorities".

Herb Barger

Jefferson Family Historian

www.jeffersondna.com

Has anyone ever considered that sally hemmings willinglty seduced TJ, being impressed by his obvious intellect and power?

I maen really, Bill clinton got seduced by Monica Lewinsky.

Monica had nothing to feed but ego, Sally had much more to gain.

Then again maybe they were actually in love.

If Nicole could love OJ then why not this?