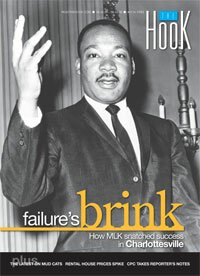

COVER- Failure's brink: How MLK snatched success in Charlottesville

Forty-five years ago last month, a young preacher and activist named Martin Luther King Jr. came to Charlottesville to speak at the University of Virginia. He and his hosts– a professor and his wife and an engineering undergrad– decided on a late-night stroll. It was a pleasant spring evening, and after sightseeing and making their way over the Lawn, they headed back across a little road behind Newcomb Hall toward the motel on Emmet Street where King was staying.

Forty-five years ago last month, a young preacher and activist named Martin Luther King Jr. came to Charlottesville to speak at the University of Virginia. He and his hosts– a professor and his wife and an engineering undergrad– decided on a late-night stroll. It was a pleasant spring evening, and after sightseeing and making their way over the Lawn, they headed back across a little road behind Newcomb Hall toward the motel on Emmet Street where King was staying.

In 1963, an interracial group was something of an anomaly in Charlottesville, even on University Grounds. Having grown up in the South, the foursome knew that just being together could be viewed with suspicion, and King's notoriety didn't help.

Suddenly a sound like a rifle shot rang out.

The professor, Paul Gaston, who had invited King to speak, assumed it was just a car backfiring. But the other man, third-year student Wesley Harris, an African American who had introduced King earlier in the evening before his speech in Cabell Hall, was gripped with fear at the thought that King might have been shot.

"It was loud," says Harris, who moved to shield King, pinning him against a stone wall below Brown College, then known as the Old Dorms.

Growing up in segregated Richmond, Harris was attuned to threats and says he responded without forethought. King was startled but unruffled.

As it turned out, the noise really had been the backfire of a passing car, and the group arrived safely at the Gallery Court Motel (later renamed and remodeled as the Budget Inn).

Although his "Letter from the Birmingham Jail" and the march on Washington lay in the future, the 34-year-old King stunned his hosts with what seemed almost like a joke amid the group's nervous laughter back at the motel.

"Yeah, it's going to happen to me sometime," Gaston recalls King saying.

No greeting party

King's 1963 journey to UVA came at a turning point in the history of the Civil Rights movement. His visit would also change Charlottesville. But its historic importance was not evident in the reception King received.

Gaston recalls that there was no official greeting at the airport on March 25, 1963: just Gaston and his two children welcomed the head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Later that night, King's speech failed to fill Cabell Hall Auditorium.

As King strolled around UVA that evening, he may well have worried that as a leader he was washed up, that meaningful civil rights gains were behind him, and that integration in the South was still another hundred years away. He had reason for despair.

The previous summer, despite months of protesting, he had failed to integrate the bus terminals in Albany, Georgia. And yet, just a week after his Charlottesville visit, King traveled to Birmingham for the most ambitious campaign of his career, a make-or-break effort whose success brought him closer to realizing his dream of ending segregation.

And Birmingham in 1963, as the history books show, was a key catapult to an event later that year in Washington, a moment that secured King's place at the pinnacle of the nation's consciousness and eventually its history: his "I Have a Dream" speech.

King's Alabama struggles

King's civil rights work began in 1955 when the actions of a stubborn bus rider changed the course of history. As every schoolchild knows, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man.

In the ensuing days and weeks, the black people of Montgomery, Alabama, walked or got rides to work in a rather than ride the segregated buses, and 26-year-old King, the new pastor of Montgomery's Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, emerged as leader of the boycott. His church and his sermons became the heart of the desegregation effort thanks to his "rolling oratory" that Gaston and other locals still vividly remember.

Months later, King's arrest and conviction for "conspiring to boycott" secured his position as spokesperson for civil rights initiatives and brought national attention to the cause.

In his Charlottesville speech, undoubtedly recalling his experience in Montgomery, King exhorted people jailed for violations of unjust laws to "transform the jail from a dungeon of shame to a haven of human dignity."

In Alabama, King had not only made his Montgomery jail cell a place of dignity, he made the incident a public relations nightmare for that city. The result was that on December 21, 1956, one year after the boycott began, the Supreme Court struck down the local bus segregation law, and Montgomery blacks again boarded the buses, now sitting anywhere they wanted, a major victory for King.

Yet when King arrived at the Charlottesville Airport eight years later, his presence attracted relatively little fanfare. In an article published the day of the speech, the Cavalier Daily lauded his achievements, although it inaccurately described him as the "vocal leader of the NAACP."

No other print media offered any advance notice. Had they been paying attention, locals might have recognized King from the publicity generated by his efforts in Albany.

The Albany struggle began in the late fall of 1961 when several blacks were arrested for protesting segregation at the city's bus terminal. King went there in December to rally the protesters. Between December 1961 and August 1962, King traveled intermittently to Albany to focus national attention on the town.

But during the eight months of protests and demonstrations, King and other non-violent activists were stymied by local officials who avoided using violence themselves. In Charlottesville, King claimed that his group's non-violent strategies "baffle those who resort to violence." But the Albany sheriff's non-violent strategies proved equally baffling.

He was arrested on three occasions in Albany, but his incarcerations never managed to spark the indignation of the national press or draw federal intervention. At the end of 1962, King and his organization had learned valuable lessons in Albany, but he was depressed by the outcome and by the sense that the movement's momentum had been lost. According to Taylor Branch, author of Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, the dynamic leader was "on edge" during this time and "exhibiting physical signs of stress." King worried that his star had fallen and that his accomplishments in the civil rights struggle lay behind him.

Integration in Charlottesville

As a university town, Charlottesville in the 1950s probably had a few more progressive thinkers than other southern cities, but in essence it still looked much like the rest of the Jim Crow South.

Schools, for instance, were still firmly segregated. Charlottesville's black students went first to Jefferson Elementary and then to Jackson Burley High School on Rose Hill Drive. The latter, a modern structure the city had built in 1951 to demonstrate its "separate but equal" vision for education, had helped deflect lawsuits from black parents claiming unequal facilities. White students went to any of six local elementary schools and then on to Lane High School (now the County Office Building) on McIntire Road.

The city's schools had been integrated in 1959, four years before King's visit, but only after an ugly episode when schools were closed for five months. The parents of local black students had sued in federal court to gain access to white schools under the 1954 landmark Brown v. Board decision.

City officials fought the federal court suit, appealing and stalling as long as possible, but on May 10, 1958, their appeals were finally exhausted, and courts ordered the schools to admit black students. Faced with the prospect of integrated schools in Virginia, Governor Lindsey Almond, a leader of Virginia's "massive resistance" movement, shut down Lane and Venable Elementary rather than allow black students to enroll. Thus, during much of the 1958-1959 school year, Lane and Venable sat empty, and parents of the affected black and white students held segregated classes in their basements.

However, on January 19, 1959, the students won a reversal of the governor's order in court, and in September three black students enrolled at Lane and nine at Venable. Five years after Brown, African-American students were able to thrust one foot through the door in whites-only Charlottesville.

But progress was slow. By 1962, the number of black students in formerly all-white City schools had grown from 12 to only 35.

While UVA had also opposed integration, black students had managed to enroll in the University's professional schools because the state could not provide a separate school in every field. The first black student had enrolled at the Law School in 1950, and a few more had slowly trickled to other university schools in the following decade.

But it was not until 1962, the year of King's visit, that UVA's oldest and largest school, the undergraduate College of Arts and Sciences, enrolled a black student in its freshman class.

The Charlottesville that King visited in 1963 had thus managed some token integration, but it was still largely a city where black citizens drank at separate water fountains and sat in the balcony at movie theaters. Charlottesville still had a poll tax, and few of the restaurants or motels in town had ever served a black patron. King himself was not welcome at the city's largely whites-only restaurants, so his hosts took him south of town to a little place called Bren-wana.

Now demolished, Bren-wana was a restaurant/nightclub on Route 29 South owned by late African-American entrepreneur Edward Jackson.

"There was no place to have dinner in town," Gaston recalls today. "It was the only place where blacks and whites could eat together."

'Controversial' speakers

In the month before King's visit, a newly formed student group, the John Randolph Society, sponsored a "controversial speakers series" and invited Gus Hall of the American Communist Party and George Lincoln Rockwell of the American Nazi Party.

"Students in universities everywhere were trying to bring in controversial speakers [because they generated] great excitement, great crowds," recalls Paul Saunier, assistant to Edgar Shannon, UVA's president at the time. The tactic was successful, as the speakers garnered considerable attention in statewide news reports and in editorials in the Washington Post and the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

The University struggled with the situation. Saunier says the administration did not want to veto the speakers or discourage the free exploration of ideas, however controversial, on the grounds of Jefferson's university. In the end, though, the two figures, voicing sensational appeals to the left and to the right, packed Cabell Hall and sparked considerable debate. According to the Cavalier Daily, students in the audience responded to Rockwell with derisive laughter and to Hall with "booing, occasional pounding of feet, and so forth."

King's speech was similarly worrisome to UVA officials, according to then third-year student Bill Leary, vice-president of the student chapter of the Virginia Human Relations Council, the group that had officially invited him. Based on Shannon's response to the visits of Hall and Rockwell, the University was not likely to voice outright opposition to King, although officials, including Shannon, worried that violence could break out and bring UVA negative attention.

In fact, as the Cavalier Daily reminded readers, King had not been allowed to speak at Washington and Lee College (now University) in nearby Lexington the previous year. Saunier says he worried that "some redneck would throw something" and start a fight with the students. University officials wanted to restrict the event to faculty, students, and spouses as they had with Hall and Rockwell, but Leary worked hard to ensure that African-American community members would be allowed to attend.

"We refused to budge," says Leary. "There were precious few black students at the time."

Most of the 100 or so black faces in the crowd were townspeople. Although the room held 1,200, various press accounts say that only 800-900 people turned out to hear the man who would soon enthrall a crowd of over a quarter of a million people in the nation's capital.

Conspicuously absent

Although it didn't deliver a full house, Charlottesville did provide enthusiasm. King garnered standing ovations both before and after his hour-long talk.

Conspicuously absent were University officials– not only administrators, but members of the Student Council as well. In 1963, King was not, Gaston explains, "someone who was really safe to celebrate."

King gave lots of speeches in those days– to conference groups, church congregations, potential financial supporters, and university audiences. His goal was to spread the message of the civil rights movement and to impress his listeners with the logic and moral appeal of his campaign. His Charlottesville speech, excerpts of which were printed in the Cavalier Daily and the Charlottesville Tribune, was what Gaston calls "his standard speech"– except, perhaps, that it contained several references to Thomas Jefferson.

In closing, before fielding questions from the audience, King used the signature words he was to make famous later that summer: "And we must maintain faith in the future. We will be able to speed up the day when all God's children can sing the Negro spiritual, 'We are free at last; thank God, we are free at last!'"

Was King's appeal for integration and equal opportunity in the South successful? Did the audience accept his call to non-violent action?

Ben Warthen, then an undergraduate from Richmond and later a member of the UVA Board of Visitors, attended the speech with some fraternity brothers.

"You don't want the world to walk by your front door and not go to the door and see what's happening," Warthen says to explain why he went. But what he remembers is the cerebral rather than the emotional appeal of the talk. "There was no epiphany or revelation," he says. "He spoke logically."

George Nicholas Slater of Upperville, a fellow fraternity brother, remembers a "fairly quiet crowd." King wasn't a minister preaching a sermon, he remembers. "It was more of a talk– he was impressive and poised, quite sincere, but pretty emphatic about his points."

The intellectual power of King's argument struck other listeners as well. For Wesley Harris, the student who protected King from the "gunfire" sound later that evening, most memorable was the powerful intellectual impression King made on the audience, many of whom may have come expecting to hear some rusty country preacher.

"To see him up close, to shake his hand, to share a meal with him, just King himself, alone and without an entourage," recalls Harris today, "it was an important event in my life– a cornerstone in my experience."

"I'm sure the people had come expecting a firebrand," says Slater, noting that the crowd was impressed to find instead a "poised, sincere" man on the podium. And while the fraternity brothers recall the speech as "respectful" and "not boisterous," Gaston remembers that some blacks in attendance surged forward at the end, just wanting to touch King.

"It was electric," says Gaston. "The dynamism that the man suggested was impossible to believe unless you actually saw it."

King's triumphs in 1963

That night, while they were all sitting in the motel room chatting, King made several telephone calls during which he was quietly absorbed in discussions that made no sense to the others, according to Gaston.

Though no one in Charlottesville was aware of it, King was already focused on Birmingham, the site of SCLC's next major struggle, and the one that would restore the movement's momentum.

According to biographer Branch, King and other SCLC leaders had decided two months earlier to make Birmingham their next target. During his Charlottesville visit, King reviewed strategies for the protests that– in light of the failure in Albany– required more carefully strategizing. He was particularly concerned about having enough people to participate in the Birmingham marches.

On Wednesday, two days after his visit to Charlottesville, King flew back to his home in Atlanta in time to take his wife, Coretta, to the hospital for the birth of their fourth child. And one week after his visit to Charlottesville, King slipped quietly into Birmingham and onto the stage that he believed was going to make or break the civil rights movement.

Several months later, the whole nation watched the evening news as Birmingham Police Chief Bull Connor's officers blasted marchers with high pressure fire hoses and terrorized black children with police dogs– images etched in newsreel footage and in the nation's memory: the final, dying days of the Jim Crow South.

Meanwhile, back in Charlottesville, a bi-racial group of students and faculty members– the Charlottesville-Albemarle Chapter of the Virginia Human Relations Council– met for an end-of-year picnic. Since the late 1950s, the Council had been patiently working to break down the color barrier in Charlottesville, with public talks on racism and prejudices. But having heard King's rallying call and seen the shocking news footage from Birmingham, they decided to resort to sit-ins as a way to push the issue of integration more forcefully, to have "their own little Birmingham," as the Alabama-born Gaston remembers.

"You wanted to be a part of that whole undertaking," says Leary. "King fired your desire and sense of obligation to do something."

Buddy's on Emmet

Buddy's Restaurant at 104 Emmet Street resisted such efforts. On the first night members of the Council tried to get served, workers at Buddy's resisted and in the days that followed stopped them at the door. In response, the Council picketed outside Buddy's and endured verbal abuse from hecklers.

On Memorial Day 1963, several restaurant patrons had had enough of the protests and heatedly berated those in line. When Gaston crossed the street to call the police, two men attacked. He dutifully remembered his recent training in non-violence.

"He hit me once hard across the face," says Gaston of one of the men, "and then again pretty hard. And the third time not so hard; and a fourth time, he just sort of grazed me."

As King had suggested, the man was baffled by Gaston's refusal to fight back, and Gaston remembers the man staring "with troubled eyes."

Oddly enough, Gaston was arrested in the incident. Although acquitted by the judge, Gaston says he received a stern lecture from the bench, the judge declaring that he and his group had "provoked" the violence.

Differing reactions

Looking back on the loud sounds on Emmet Street, Gaston says he hadn't actually thought of a gunshot until he saw Wesley Harris move to protect King.

"Hey, I could have done that," Gaston says today, with obvious regret. A decade later, Gaston would pen a seminal volume called The New South Creed, which exploded some of the South's most comforting myths. But in 1963, Gaston says, the young professor, who'd been raised in the utopian Alabama community of Fairhope, simply wanted everyone to get along.

Harris, the black student who grew up in segregated Richmond and recalls occasionally having to fight his way to school some days, was obviously more aware of the potential danger. He went on to live on the Lawn, earn two graduate degrees at Princeton, and head the department of aeronautics and astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Today, he agrees with Gaston that his actions were "totally spontaneous" for a young man living in a world so divided by race.

As for King, although he may have considered himself a failure when he came to Charlottesville, his visit inspired locals to continue the fight to create a colorblind society with equal opportunity for all citizens.

Less than two months later, the approximately 1,000 arrests in Birmingham sparked outrage that energized King's movement as much as King had energized Charlottesville.

And that August, King stood at the base of the Lincoln Memorial to give the speech that cemented his place in history. Charlottesville residents who'd been present in Cabell Hall that night in March had already had a taste of the dream.

Dr. Todd Barnett is the Head of School at Field School, a boys' middle school in Crozet. An early version of this story appeared in C-Ville Weekly eight years ago.

CIVIL RIGHTS TIMELINE– three tracks: VA, MLK, U.S.

MLK January 15, 1929– Martin Luther King Jr. born in Atlanta, Georgia

US June 5, 1950– U.S. Supreme Court rules in Sweatt v. Painter that separate is not equal

VA July 14, 1950– UVA Law School rejects Gregory Hanes Swanson on the basis of race

VA September 5, 1950– Federal court orders UVA to admit Swanson; he enrolls 10 days later.

VA April 23, 1951– 16-year-old Farmvillian Barbara Rose Johns organizes a student strike in Prince Edward County

VA On May 23, 1951– NAACP files Davis v. Prince Edward, later consolidated in Brown v. Board

US May 17, 1954– Supreme Court demands integration in Brown v. Board

US May 31, 1955– Supreme Court tells states to integrate schools at "all deliberate speed"

VA February 24, 1956– Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr. launches policy of "massive resistance"

MLK December 21, 1956– Montgomery bus boycott ends with federal court order forcing integration

MLK January 10, 1957– Southern Christian Leadership Conference founded with King as president

VA September 18, 1958– Governor Lindsay Almond closes Lane High School and Venable Elementary to avoid court-ordered integration

VA September 19, 1959– Three black students at Lane and nine at Venable break local public school color barrier

MLK August, 1962– King's eight months of protests in Albany, Georgia fail

VA September 19, 1962– First black undergraduate signals integration of UVA

VA/MLK March 25, 1963– King speaks at UVA's old Cabell Hall

MLK April 12, 1963– King arrested in Birmingham

VA May 30, 1963– Sit-in at segregated Buddy's Restaurant leads to attacks on protesters

MLK August 28, 1963– "I Have a Dream" speech at the March on Washington

US January 2, 1964– passage of the Civil Rights Act

MLK December 10, 1964– King awarded Nobel Peace Prize

US August 6, 1965– passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

MLK April 4, 1968– King assassinated in Memphis

#