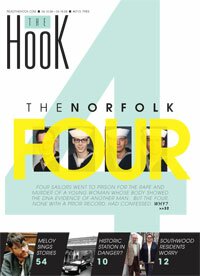

COVER- The Norfolk Four: Clemency petition sits on Kaine's desk

It was a curious time for Danial Williams to commit murder.

On that fateful Tuesday, the 25-year-old Norfolk sailor had been married to his longtime girlfriend for less than two weeks, and she was recuperating from surgery for ovarian cancer. His parents had just arrived for a visit from Michigan and were staying at a nearby campground.

The foursome was heading for dinner that July evening when police, investigating the shocking discovery of a neighbor's dead body earlier in the day, interrupted the plans.

Just a few questions. Shouldn't take long.

If Danial drove his truck downtown, he might be able to join the rest before they'd finished eating.

Almost 11 years later, Rhea and Norman Williams have yet to see their eldest son again other than in a courtroom or behind bars. After more than nine hours of grilling, Danial Williams– today the subject, along with three others, of clemency petitions before Governor Tim Kaine– confessed to the rape and murder the previous evening of Michelle Moore-Bosko, a vivacious 18-year-old woman slain while her Navy husband was at sea.

Three of the men, including Williams, are serving double life terms. The fourth has completed an 8.5-year sentence for Moore-Bosko's rape. All four confessed to crimes that the evidence, contrary to claims by Norfolk police and prosecutors, says they did not commit.

The result is one of the most bizarre stories in criminal justice annals anywhere, a tale that showcases the flaws in police interrogation techniques, the dangers of prosecutorial myopia, and the potential for innocent people to spend years or lifetimes entrapped by law enforcement, juries, and judges run amok.

***

According to a confession dictated at 7am after a night of interrogation, Williams beat Moore-Bosko with his fist and "a flat-soled, hard shoe" after raping her in a fit of sexual frustration.

Wait. Make that stabbed her to death.

An amended statement four-and-a-half hours later cleaned up the error. "I was putting my hands over her mouth, pushing her mouth closed, trying anything to keep her quiet. I started really panicking ... and I saw a knife. I picked it up, and I stabbed her about three times," the transcript reads.

A murder. A confession. Case closed.

A couple of decades ago, that would have been that. But not after the realization in the mid-1980s in Great Britain that the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in human tissue or fluids– blood, hair, semen– can pinpoint criminals with a precision only dreamed of by Hercule Poirot or Sherlock Holmes.

Conversely, DNA can exonerate the innocent, which is almost surely what should have happened when test results on cells taken from under Michelle's fingernails and semen found on her body and a blanket came back a few months later eliminating Williams as the source.

Norfolk police and prosecutors adopted an alternate theory of what happened on July 8, 1997: if the genetic material did not belong to Williams, then someone helped him murder Michelle. Williams had, after all, confessed.

The most likely accomplice was Danial and Nicole Williams' roommate, Joe Dick. After a seven-hour interrogation, Dick– a 21-year-old sailor and Maryland native with intellectual limitations– confessed as well. Then, confound it, his DNA also turned up a mismatch.

What evolved from there is a stunning example of the spiraling effects of clinging to a flawed premise. Chasing an elusive DNA link, police arrested more and more suspects until the count stood at seven white males, young Navy sailors at the time of Michelle's death, none with any prior criminal record.

Inconveniently, two of the seven produced solid alibis, but four confessed– yet still there was no DNA match.

Then, out of the blue, a prison inmate convicted of raping a teenager less than two weeks after Moore-Bosko's death and just over a mile from her apartment, wrote a letter bragging that he was Michelle's killer. The recipient took the letter straight to the police.

Soon, detectives had a fifth confession, this one from Omar Abdul Ballard, a black man who knew Moore-Bosko through a mutual friend. This time, the DNA fit.

For prosecutors and police, a new puzzle diminished the satisfaction of clearing up the DNA mystery. Ballard had only a filigree of connection to any of the other seven suspects. Worse, he claimed to have acted alone. "Them four people that opened their mouths is stupid," he told investigators.

But the government had traveled too far to turn back. Over 20 months, investigators had spun an ever-more-elaborate theory of an impromptu gang rape and murder, hatched at the midnight hour in the parking lot of garden apartments near the Norfolk Naval Station. Police were not about to let that narrative go. They inserted Omar Ballard as an eighth member of the gang.

Then the real confusion began.

Danial Williams, due to be sentenced to life in prison in a plea deal that spared him execution, balked after Ballard appeared. Williams said his confession was concocted out of a desperate fear of execution and desire to end a grueling interrogation.

Judge Charles Poston would have none of it; he sentenced Williams to two life terms anyway.

Joe Dick– whose story had shifted multiple times to accommodate the ever-growing list of suspects– continued to confess remorse. He had come to believe in his own guilt. Dick also was sentenced to two life terms.

Eric Wilson of Pleasanton, Texas, the third man charged, had recanted his confession almost immediately. But when he went to trial, Dick testified against him.

"Innocent people do not confess," prosecutor Valerie Bowen told the jurors, who recommended 8.5 years for rape after listening over and over to a recording of Wilson's confession.

Derek Tice, who had supplied the names of the fifth, sixth, and seventh men arrested after being tracked down in Orlando, Florida, also recanted his confession. Rejecting a plea deal, he went to trial charged with capital murder. Again, from the stand, Dick parroted the government's version of events.

A sullen Omar Ballard took the stand and disingenuously denied having anything to do with the murder. (Today, he is back to acknowledging guilt and insisting that he acted alone.)

The jury listened to an audiotape of Tice's confession, but no recording existed of his interrogation; he, too, was sentenced to two life terms. At a re-trial in 2003, jurors again heard the audiotape but not an expert on false confessions. Jurors have the ability "to understand that confessions can be coerced," said Judge Poston, denying the defense request. The life terms stood.

In March 2000, Ballard pleaded guilty and received two life sentences.

Without Tice's cooperation, the government's case against the other three men charged in the murder collapsed, which most likely would have happened anyway. One of them had a worksheet and an ATM withdrawal placing him in Warminster, Pennsylvania– hundreds of miles from Norfolk– at the time of the crime. The other could produce computer, Internet, and phone records showing him talking and e-mailing throughout the night with a girlfriend in Australia.

Such inconvenient facts do not dissuade former Norfolk prosecutor D. J. Hansen and others who investigated and tried the five cases that led to convictions from contending that too few men were convicted, not too many.

"Our view is they were all [eight] involved," says Hansen, now a prosecutor in Chesapeake, in a recent telephone conversation.

However, an impressive list of experts with no ax to grind– former Attorneys General Richard Cullen, Anthony Troy, Stephen Rosenthal, and Andrew Miller; former Virginia Bar Association President Tazewell Ellett, and a dozen former judges and federal prosecutors from across the nation– say otherwise.

As they point out, not a shred of evidence except confessions rife with inconsistencies and errors links the convicted men, except Ballard, to the crime.

By the prosecution's theory, eight men practically strangers to each other converge in an apartment complex on a summer night and conspire to commit murder. Undetected by anyone and without leaving a mark on the doorway, they gain entrance to the Moore-Bosko apartment where they take turns raping and stabbing Michelle.

Yet nothing in the apartment was awry, the wounds were inconsistent with multiple assailants, and only one man left forensic evidence behind. The Norfolk Four were convicted anyway.

"It is crystal clear that only one person committed this crime," said Cullen, a former U.S. attorney and chairman of the law firm McGuireWoods, at a press conference earlier this year. "Justice without doubt dictates that the governor act."

***

"Well, you know, my son, when he was ten years old, there is no way you could convince him that he raped and murdered somebody," said Gary Close, commonwealth's attorney in Culpeper County and a reporter at the 1984 trial of Earl Washington Jr. "He'd deny it, and I don't buy that at all."

Soon after Washington was pardoned in 2000 in the death of a Culpeper housewife, Close expressed disbelief that an innocent man– even one with the I.Q. of a 10-year-old– would confess to a murder he did not commit.

At the time, confusion remained about DNA evidence in the case. Today, all doubt of the former death row prisoner's innocence is erased, and Close has been proven wrong.

Counter-intuitive as the false confession of a mentally challenged farmhand might be, it's a far greater leap to conclude that four men, some of normal intelligence, would admit to a crime to which they had no connection.

"People ask me, ‘Why would a normal, sane individual confess to a crime he didn't do?'" says Jim Trainum, a Washington, D.C., police detective who grew up in Henrico County and now lectures on interrogative pitfalls, including false confessions.

"I say, ‘Why would a normal, sane individual confess to a crime he did do?'"

In both instances, Trainum contends, the motivation is the same: interrogation techniques lead them to believe "It's to their advantage to tell me what I want to hear."

The starting point for unraveling the mystery of false confessions is to accept that they occur. The evidence is indisputable. Scores of false admissions– sometimes including multiple confessions in a single case– have been documented and confirmed over recent decades.

One of the most notorious occurred in April 1989 after a 28-year-old investment banker was raped and brutally beaten as she jogged through Central Park. Of five teenagers convicted of the crime, four confessed on videotape, some with their parents in the room.

Then in January 2002, a known serial rapist and murderer admitted that he alone had attacked the jogger. DNA matched, other alleged evidence disintegrated, and the young men– who were up to no good in Central Park that night, but had nothing to do with the jogger– were released.

In another stunning case, dubbed the Buddhist Temple Massacre, nine people were murdered early on August 10, 1991, at Wat Promkunaram outside Phoenix, Arizona. Police extracted confessions from five men, some of whom seemed to supply details unknown to the police.

Astonishingly, the murder weapons turned up later in the possession of two teenagers who described the crime scene in detail, providing incontrovertible evidence of their guilt.

In a seminal study published in the North Carolina Law Review in March 2004, Northwestern University law professor Steven Drizin and University of San Francisco associate professor of law Richard Leo analyzed 125 cases of what they contend are proven interrogation-induced false confessions between 1971 and 2002. They included the case of the Norfolk Four.

Drizin and Leo acknowledge that understanding false confessions was far easier in the 19th and early-20th centuries, when punching, kicking, suffocation, and other tortures were accepted as legitimate investigative tools.

In the modern era, psychological interrogation has replaced such crude forms of extracting information (at least on U.S. soil, where the legal system would hardly tolerate tactics employed by American troops in Guantanamo Bay). But verbal abuse, physical discomfort– and even lying about the results of polygraph tests, the existence of eyewitnesses, or the presence of damning evidence– are all sanctioned.

An interrogation is "designed to break the anticipated resistance of an individual who is presumed guilty," Drizin and Leo explain. "It is intentionally structured to promote isolation, anxiety, fear, powerlessness, and hopelessness."

Once the suspect feels trapped, the next step is for police to convince him that confession is the most logical response. Not only will cooperation have the immediate benefit of ending a mentally excruciating experience; it also may assure more lenient treatment down the road.

At that point, a seemingly illogical act becomes logical.

Unfortunately, techniques designed to trap a guilty suspect can sometimes ensnare an innocent one. It's up to police to make sure that the details of a confession fit and that the suspect didn't glean his information from the interrogation itself.

As Jim Trainum knows, the thrill of wrapping up a case can steamroller objectivity.

Tweedy, rumpled, looking more like a college professor than a top detective in a big-city police department, Trainum, 52, sits in a soon-to-be renovated office at the Henry J. Daly Metropolitan Police Headquarters, a gunshot away from the nation's Capitol. Dirty beige walls, battered file cabinets, and a tangle of cords and wires will soon be transformed into a home for thousands of cold-case files, the genetic material for the Violent Crime Case Review Project that Trainum heads.

Grinning, his aging choirboy face framed by a short beard and graying hair, Trainum guesses that few of his friends when he was growing up in Richmond in the early 1970s would have envisioned him where he is today, as he displays none of the swagger or tightly wound intensity of cops on shows like Law and Order or CSI.

"I can't talk sports, street talk," he says. "I'm not a hard-ass."

But success in some high-profile homicide cases– including the so-called Starbucks murders that claimed three workers at a Georgetown coffee shop in 1997– showcased Trainum's abilities. Even without a college degree, he brings a probing, analytical curiosity to cases. He also has enough humility and integrity to question his own assumptions.

Trainum's most popular training lecture, "False Confessions and Investigative Pitfalls," grew out of a personal debacle when he learned how easy it is to take a false confession.

"I'm just a cop who made a mistake, and I wanted to understand why," he says.

The year was 1994, and Trainum was newly assigned to the homicide division. A Voice of America employee who had gone missing was found beaten to death near the Anacostia River. The man's credit card had been used for a Chinese dinner, and an ATM camera captured a white female using the man's card.

A tip pointed detectives to a woman who resembled the ATM photo, whose father worked at Voice of America and who associated with a tough gang. After a couple hours of interrogation, her denials gave way to an admission of credit card fraud and then, after a couple more hours, to murder.

Nowhere along the way was there any shouting or threatening, Trainum says, just a persistent hammering on her apparent guilt. In her confession, "she was giving us amazing things that she shouldn't have known: ‘I went to this restaurant; I purchased this type of food,'" Trainum says. "She's a cold-blooded little bitch in the recap." Case closed.

Almost.

Following up on evidence for a trial, Trainum retrieved the checkout log from the homeless shelter where the woman lived. There, in her own handwriting, was a clear alibi for the hours of the crime.

"Oh, my god, I almost retched all over the car," he says. He and his colleagues tried to think of any way possible that the murder could have occurred between her shelter comings and goings. "We were almost having her beamed up by Scotty," he says.

In the end, they had to admit that she could not have been in two places at one time. The confession was a ruse.

As luck would have it, a portion of the interrogation had been videotaped, and Trainum studied the detective-suspect exchange. At first, he saw nothing obvious. But over time, he recognized that he had picked up only on comments that fit his theory, while ignoring contradictory ones.

And, much as he thought the police had not revealed any details, they had. How did she know so much about the Chinese dinner, for instance? Because they had shown her the bill when asking if the signature was hers.

"We can all make mistakes. We can go down the wrong path. You have to be able to spot it, recognize it, and say, 'That's where I went wrong,'" Trainum says. "With a jury, a confession trumps everything."

Armed with such expertise, Trainum agreed to review the Norfolk Four case for the high-powered team of New York and Washington D.C. lawyers working pro bono to clear Danial Williams, Joe Dick, Eric Wilson, and Derek Tice.

The attorneys offered a stipend, but Trainum refused to take it. "I don't like hired guns," he says.

His conclusion?

"This is like a perfect storm. I understand what happened in the first couple [of confessions]. But after a while, somebody should have stepped in and said, ‘This is a train wreck,'" he says. "I have no clue in my heart why these guys aren't out of jail."

***

Sussex II State Prison, rising out of southeastern Virginia's peanut farms and piney woods, seems as gray and blank as the lives it warehouses. Through a glass window, Derek Tice speaks into a telephone receiver and tries to make sense of the nonsensical.

"I spent my entire life believing in the justice system," he says during an interview in mid-March. "I still believe in that, but I'm sitting here in an alternate reality."

By his recollection, Tice's life fell apart on June 18, 1998. Then a 28-year-old ex-sailor working as a steel press operator and living with his girlfriend in Orlando, Tice got a phone call from a Norfolk police detective. The man said he needed to clear up some details before Danial Williams– a good friend of Tice's– went to trial. Tice suspected nothing.

The phone rang again at about 11:30pm. A Florida police detective asked Tice to step outside. "I put on shorts and walked out on the porch of the trailer, and all hell broke loose," he said. "There were at least 12 officers in bullet-proof vests, shotguns, pistols drawn."

When he was extradited to Virginia, "I even told my girlfriend: ‘Don't worry. When I get to Norfolk, we'll straighten it out, and I'll be back in a week.'"

A smallish man with dark hair and pale skin, Tice flashes a painful grimace when asked how he came to confess. "I hate this part, getting back into that room or anything about it," he says.

As Tice describes it, the interrogation space was tiny, with no windows, one door, and "yucky yellow walls," permeated by the stench of urine and sweat. Detective R.G. Ford stood over him yelling, "‘You're an f-ing liar, Derek. We know what you did ... You keep lying, and you're going to die.'"

Ford told Tice that an eyewitness could identify him and that his fingerprints were found at the scene. And later, "‘You make this statement, and we'll stand up for you, but if you continue saying this bullshit, you're going to die.'

"I make it sound so casual," Tice says, "but it wasn't. It was hell on earth."

At some point the prisoner concluded: "I'm not getting out of this room until he hears what he wants to hear."

That Tice publicly persisted in the confession for months, even naming additional men as part of the conspiracy, reflected his determination to stay alive, he says. "Self-preservation is No. 1 to humanity, and it kicked in."

In an interview with the Virginian-Pilot in September 2006, Detective Ford– since retired– denied yelling or physically threatening Tice. He acknowledged, however, that he lied in telling Tice that multiple co-defendants would testify against him and that DNA linked him to the scene.

Because the interrogations weren't taped, it's impossible to reconcile Ford's assertions with the claims of Tice and others of the Norfolk Four that they were verbally battered.

In a letter to the Pilot dated January 11, 2006, former prosecutors D.J. Hansen and Derek Wagner laid out several reasons why the chilling and often-graphic confessions ought to be believed: three separate juries heard Tice's and Wilson's claims of innocence and discounted them; Dick testified three times "under withering cross examinations" that he and the others were guilty; and the absence of forensic evidence doesn't prove innocence.

"Criminals often do not leave evidence of their presence behind at a crime, or even homeowners in their own home," the attorneys wrote.

Moore-Bosko's family also continues to believe that those convicted of her crime are guilty.

But eight people leaving no evidence whatsoever of a frenzied gang rape? Not even an apartment in disarray?

To Larry McCann, a 26-year veteran of the Virginia State Police who analyzed the case for the defense team, that's simply ludicrous.

"The apartment was neat, clean, and nearly pristine," he wrote in an op-ed piece defending the Norfolk Four. "If more than one attacker had been involved, the condition of Moore-Bosko's apartment after the murder would have been vastly different."

Nor did any jury get a full sense of the multiple discrepancies and revisions in the confessions.

Tice said the assailants used a claw hammer to get into the apartment, but the door was undamaged. Dick progressed from saying that he and Williams alone stabbed Moore-Bosko to a scenario in which eight people shared the knife. Yet, three lung-penetrating stab wounds were of an angle and depth consistent with a single assailant. (Other superficial wounds were tightly clustered in the same area of the left breast.) At least two of the Norfolk Four claimed to have ejaculated, although only Ballard's DNA was found. Details about the location of the body, the nature of the attack, and the method of entering the apartment all varied.

Only Ballard correctly described the knife and gave a detailed description consistent with the actual crime scene, including his riffling of Moore-Bosko's purse.

Discrepancies aside, former prosecutors Hansen and Wagner raise a troubling point: What is one to make of Joe Dick? What would possess an innocent man to continue confessing guilt and accusing others, even after the clear culprit had emerged?

The answer is less puzzling than one might think. Just as it's undeniable that false confessions occur, it's also indisputable that some false confessors become convinced of their own guilt. The phenomenon even has a name: coerced-internalized false confessions.

As described by British psychologist Gisli Gudjonsson, one of the pioneers of the literature of false confessions, the suspect begins the police interview with a clear recollection of not having committed the alleged offense. But "subtle manipulative influences by the interrogator" gradually bring the suspect to distrust his own recollections and beliefs.

Riddled with self-doubt and confusion, he simply alters his perception of reality.

What sort of person would make that leap? Experts say a highly suggestible, insecure person, plagued by low self esteem, by anxiety, and by a fear of negative evaluation, one schooled to defer to authority and coveting the sort of positive feedback that a confession might produce.

In other words, Joe Dick.

A former altar boy, church volunteer, and Boy Scout who grew up in Baltimore, Dick is uniformly described as an "odd duck," with intelligence on the low end of normal. A childhood head injury may have exacerbated his problems. Cowed by a domineering father, a social outcast in high school, he displayed a cognitive and social fragility that trailed him to the Navy.

"Joe was a... he needed special attention," said Senior Chief Petty Officer Michael Ziegler, Dick's boss at the time of the murder, when he testified in an appeal hearing on Tice's conviction. "He had a hard time following simple instructions."

(Ziegler believes that Dick was on board the U.S.S. Saipan the night of the murder, but Dick never went to trial, so Ziegler was never called to testify. After a decade, the Navy logs that might prove or disprove Dick's whereabouts no longer exist.)

Ziegler recalled as typical an incident when he asked Dick to paint a three-inch day-glo border around a ship's doorway. "[Joe] just dipped the paint brush in the bucket and just started slopping paint all over," he said. "You could see spilled paint on the floor, and he walked through it. His footprints went across the deck. And where he got his hand in the paint and leaned up against the bulkhead, there was his handprint where he had leaned up as he was painting...That was a typical Joseph Dick maneuver."

Today, Dick is incarcerated at Wallens Ridge State Prison, a super-max facility in the far southwest corner of the state intended for the worst of Virginia's prisoners. His attorneys say he has been assaulted multiple times in the last decade by other prisoners.

Wilson completed his eight and a half-year sentence for Moore-Bosko's rape and now lives in Texas.

Williams, whose wife, Nicole, died of ovarian cancer four months after his arrest, is housed at Sussex II, about 45 miles southeast of Richmond, as is Tice.

Tice married his girlfriend in March 1999, just days before Ballard was charged with Moore-Bosko's murder. He hasn't seen his wife in almost eight years. Recently, he filed for divorce.

"I live in a 5 ½-foot by 11-foot cell with one other person, a toilet, sink, two beds. There's a 45-watt bulb burning 24-7 at eye level. I have kids tell me when I can lie down, when I can eat, when I can go outside," Tice says, describing his constricted world.

"It's, for lack of a better word, hell."

***

Clemency petitions for the Norfolk Four, filed in 2005 in the last months of former Governor Mark Warner's term, sit on Governor Tim Kaine's desk.

Resolving them is no easy matter. Kaine made headlines April 1 for staying an execution while the Supreme Court rules on lethal injections. For him to join four former Attorneys General in proclaiming innocence would cement an indictment of the criminal justice system breathtaking in scope. Yet, failure can also become a catalyst for essential reforms.

If Virginia, like eight other states and a growing number of localities– including Norfolk and Washington, D.C.– had videotaped not just confessions but interrogations, the Norfolk Four cases might have been resolved long ago. Judges and juries could have watched Detective Ford's questioning and decided for themselves what led four men to confess.

"Our experience has been great," says Norfolk Commonwealth's Attorney John R. "Jack" Doyle, who spearheaded Norfolk's recent move to taping interrogations in homicide cases. It may be no accident that Doyle, as a private attorney, defended one of the last men charged and then released in the Moore-Bosko murder. He declines to comment on the case.

On taped interrogations, however, he is effusive. "Our hand– both society's and the prosecution's office– has been greatly strengthened by having this piece of evidence," he says.

Such statewide reform might salvage a larger purpose from one of the most disastrous legal cases in Virginia history.

Richmond resident Margaret Edds covered state government and politics for years with The Virginian-Pilot before switching to editorial writing for the paper in 1996. She's written three nonfiction books about the intersection of race and government in the South, including "An Expendable Man: The Near-Execution of Earl Washington Jr." (NYU Press, 2003), and has since retired from the Pilot. She graduated from Tennessee Wesleyan College and earned her MLA degree from the University of Richmond.

Omar Abdul Ballard's DNA was found under the fingernails and inside the body of the victim.

VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS

Former Virginia Attorneys General Stephen Rosenthal, Richard Cullen, and Anthony Troy are among the many who believe that the state convicted innocent men in the case of the Norfolk Four.

PHOTO BY SCOTT ELMQUIST

Jim Trainum: ‘Why would normal, sane individuals confess to a crime they did do?'

PHOTO BY SCOTT ELMQUIST

#

11 comments

If you've ever lived in Norfolk you'd know there's nothing surprising about this. Both Norfolk and Newport News police (out of police depts in Hampton Roads) have ... how should one say... less than a sterling reputation.

It should be noted that, ultimately, in the case of the "Albemarle smoke bombers" who supposedly confessed, a jury didn't accept the "confession" of one and charges against others were ultimately dropped before trial.

Family Guy, there's one good thing that came from the smoke bomber cases. It was just one more nail in the coffin of Jim Camblos in the recent commonwealth's attorney race.

I hope Denise Lunsford is bright enough to not let a three ring circus like this jeopardize her career as the new commonwealth's attorney for Albemarle County.

I first heard about the Norfolk 4 a few years ago and am surprised that this still hasn't been resolved. I know that the appeals process takes years, but this has been a long time coming. This needs to be dealt with justly and quickly.

This article causes me to reflect on my time as a police officer, first in Norfolk for several years, then as an Albemarle County police officer for the remainder of my career.

While I have no direct knowledge of the facts of the Norfolk Four case, I do have for the behavior of the Norfolk police officers with whom I worked. Many were hardworking ethical individuals worthy of emulation. Some were not. Sometimes misplaced zeal got in the way. On occasion, purposeful misconduct occurred followed by an application of the code of silence.

However, that does not prove poor police investigative and interrogatory tactics took place in the Norfolk Four case.

Surprisingly to me, coming from the much larger Norfolk Police Department and going to the smaller Albemarle County police department in 1994, my eyes were opened even further.

Similarly as in Norfolk, many of my fellow Albemarle County police officers were competent and honorable and some were not. The surprise was the amount of misconduct and the extent to which it was accepted at ACPD. Alarmingly, not only was the misconduct frequently overlooked, sometimes those involved were rewarded.

If I hadn’t seen for myself significant amounts of police misconduct over the years including multiple examples of brutality and outright lying by police officers, even while under oath, including the lies of omission, I still might have considerable faith in our criminal justice system.

Video taping of all police actions is a good start but more is needed. Even in video taped interrogations, if there is an overzealous desire to convict a particular individual there can be significant obfuscation by police if any impropriety, or worse, occurred. I have seen this very thing at ACPD.

Much like a police K-9 needs to be kept on a leash and remain under the control of the handler, police officers all the way up the chain of command need to be on a leash of public scrutiny.

Evidence and confessions need to be supportive of each other. If the Norfolk Four are innocent, justice is not being served. We are all indirect victims of that. Potentially, any one of us could be a direct victim.

Gosh Karl, I hope people sit up and pay attention to everything you just said. Most people believe it's just one or two bad apples in the barrel, and most people believe they are eventually weeded out.

Your "rewarded" comment cracked me up. Like the one who was fired for stealing, rehired, and now he's what -- 2rd or 3rd in command?

Yeah I feel really bad for these guys and they should be given a pardon and have this mess taken off their record. I know that the Wilson guys wife and kids would appreciate it.

Karl,

I do agree with you in one point in particular. Video taping should start within all rooms of a PD and then extend outward to the communitee if Longo and others want cameras on the mall, etc..

Surely Longo and Miller would not object since they are the good guys, right? But then again Miller may not want his office taped...shhhhhhh ;)

Where's the outrage when the unjustly convicted are black?

The Norfolk Four should not spend another night in prison. But what about other innocent souls locked up in hell-on-earth this very night who ALSO have exonerating DNA evidence on their side?? Do you care about them as well?

I've read many articles on the Norfolk Four just this morning. It's not surprising that Damian J. Hansen, one of the former prosecutors and even Fasanaro who was Dick's lawyer disagree with Kaine giving these guys clemeny. You have to think why would a defense lawyer not want his client pardoned? Fasanaro knows that he messed up and if this guy gets out, it'll prove that he didn't do his job. Of course, the prosecution doesn't want their work to be overturned either. Just reading the articles, there seems to be a lot of things wrong with the cases. Aside from the confessions, none of the alleged knew any of the details of the crime scene, even when prompted by the police. There was no DNA evidence linking any of them, even though supposedly up to 7 of them had participated in her rape and murder. The house was immaculate even though they supposedly barged in and attacked her. One of them confessed that they killed her in the bedroom, dragged her body into the living room and then moved her back into the bedroom when they heard someone coming. But there was no blood trails from the living room to the bedroom, etc. I have no doubt that the jury didn't hear any of this evidence because Fasanaro didn't bring it up. Was/is he incompetent as a trial lawyer? Was he a public defender back then who was overburdened with his case load? You just have to wonder how these cases got so far with so many inconsistencies like defendants changing their testimony so many times. The police didn't even search the apartment of the defendant who lived in the same building as the victim, even after he confessed. This case stinks on all levels!!

They are guilty, period...

They didn't barge in and that has never been proved. She knew one of them well! I'm telling you that they are guilty and they are getting what they deserve.