GREEN- Double-speak: How Charlottesvillians destroy the planet

Sure, Charlottesville likes to think of itself as a green community. From the Lawn at UVA, to manicured golf courses, to vast public parks, this town in many ways surrounds green space. With all the initiatives undertaken to cut down on carbon footprints, curb waste, and devise more creative use of already existing resources, Country Home magazine just named Charlottesville one of the top 10 green places to live.

But, as with any community, there's always room for improvement. So, stifle all that "greener-than-thou" talk, Charlottesville– unless, of course, you're up for recycling all those glass bottles into glass houses.

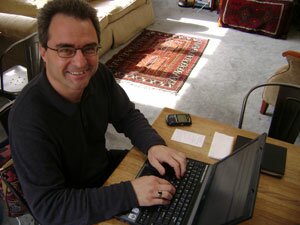

To minimize the effect of his Charlottesville-to-Richmond commute on the environment, Paul Erb sometimes telecommutes to his job via e-mail and his Blackberry.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

Regretful commuters from Charlottesville

In 1999, when Paul Erb decided he was tired of living on a teacher's salary, he found there weren't many options in Charlottesville.

"There are so many talented people concentrated here that jobs that are interesting and pay well are scarce," he says.

So, Erb widened his scope a bit and found a job working in data management with a financial services firm in Richmond.

"They made a terrific offer, and at the time gas was only $1.25 a gallon," he says. "It made perfect sense."

Now, with gas prices above the $3.10 mark all over Charlottesville, the only thing perfect about Erb's arrangement is the perfectly efficient way with which his daily commute burns up his time and money.

"That's two hours out of my life everyday, and a trip to Richmond costs me $20," he says. "I've calculated that I could take a $20,000 per year pay cut and still break even if you factor in gas and wear and tear on the car."

Plus, the former English teacher couldn't help but be reminded of a bit of his old literary companions.

"I began to feel like Wemmick from Great Expectations," says Erb. "There's a passage where Dickens describes Wemmick's commute from one part of London to another and how he can feel his face harden as he goes to work and soften on the way home."

That's not to mention his ever-expanding carbon footprint, try as Erb might to mitigate the effects of his commute.

"Driving is inherently wrong, but that's the life we've built for ourselves," he says. "I tried carpooling, but people's work hours aren't always 9 to 5, and my office is actually in Glen Allen. Most others were commuting to downtown Richmond, so it was hard to coordinate that."

Twenty-first-century technology has helped somewhat, but Erb still believes he's missing out when he's not in the office.

"I telecommute from home fairly often with e-mail and my Blackberry," he says, "but all statistics show that if you're not present in the office, you don't get as much done, and people just don't think of you when it comes to performance evaluations."

So Erb says he's jumping back into the job pool here in Charlottesville.

"I'm going to stop doing this around June," he says. "I'll be a little greener, I'd love to be able to walk or bike to work, and I'll have two extra hours every day."

In addition to making a 45-minute commute to town from Waynesboro, Carolyn Kerouac was burning up fuel in her Dodge Durango SUV until she traded it in for a more gas-friendly Hyundai Sonata.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

Regretful commuters to Charlottesville

Carolyn Kerouac is one of the thousands of people who commute into Charlottesville and Albemarle from surrounding counties. The sales director of biomedical firm Informed Care says that when she and her family were thinking of buying a new house in the area, they looked at real estate prices both in Charlottesville and over the mountain in Waynesboro and decided it was a no-brainer.

"It wasn't even an option to buy a house in Charlottesville," she says. "The prices had gone way up from when we first got here in 2000, and I just couldn't justify spending that kind of money for a house."

So, despite the fact that her office was then located along Route 29 just past Hydraulic Road, the Kerouacs moved to Waynesboro, creating a daily 45-minute commute.

It's a phenomenon not exclusive to Kerouac, but one that architect and developer Bill Atwood is betting he can stem by providing Charlottesville-based employees a viable alternative. That's why he just purchased the Under the Roof building on West Main, and the 0.384 acres on which it sits, for $3.2 million.

"Our mission is to get some retail down there and good food service, but mostly affordable, work-force housing," Atwood told the Hook at the time of his big buy. "Most of the people who work for me can't live in Charlottesville or Albemarle, and that's terrible. They have to live in Orange or Waynesboro."

Atwood says he didn't ask Under the Roof's owners to "drop one penny," off their asking price because he's so confident people are thinking greener.

"People are realizing that they can leave a smaller carbon footprint if they live in the city," he says. "People can walk to the amenities they want, except maybe golf courses."

Atwood's apartments and condos won't have much to offer families, though, as most of the people who buy up such spaces are either recent empty-nesters or young workers without children. And not everyone is as fortunate as Kerouac. Tired of the commute to Charlottesville, she and her husband moved their company to Crozet.

"It's almost exactly half the distance," she says. "I'm there in about 15 minutes."

A few of the 128,000 registered vehicles in Charlottesville and Albemarle are seen here parked in the Water Street parking lot.

FILE PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

One car for every 1.03 people

During his successful 1928 presidential campaign, Herbert Hoover promised Americans "a chicken in every pot, and a car in every garage." Little did he know at the time that not only would the "car in every garage" prophecy come true, but now it's closer to "a chicken in every pot and a steering wheel in every hand."

According to a 2005 Department of Transportation study, there were 247,421,120 vehicles registered in the United States, or one car, truck, SUV, or other gas-guzzling, carbon-spewing vehicle for every 1.18 Americans.

But locals know a deeper kind of auto eroticism. According to VDOT, the 132,000 people who live in either Charlottesville or Albemarle are the proud drivers of 128,000 registered vehicles. That's nearly a one-to-one ratio– one car for every 1.03 people.

While the CO2 emissions alone are enough to make Al Gore gag, consider also that every car has to have some place to park. A town with 128,000 cars needs at least 1,000 acres of space on which to park them. Factor in another parking space for work, and another for shopping, restaurants, and anything else that qualifies as "going out," and we're talking 3,000 acres of parking for Charlottesville and Albemarle alone.

How big is 3,000 acres? Imagine a football field. Now imagine 756 of them. Now imagine all of them paved over.

Fortunately for Charlottesville, government and real estate developers have considered the environmental (not to mention the economic) consequences of paving 3,000 acres of paradise and putting up a parking lot. That's why they have tended to build vertical parking decks– 11 in the last 36 years (see p. XX for more).

The Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority's ambitious new dam plan would mean clear-cutting much of the Ragged Mountain Natural Area.

FILE PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

Mega-reservoir could mean mega-damage to the environment

Every day, a little more sediment seeps into the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir, reducing its capacity to quench the thirst of our growing population. Dredging it, however, will cost millions, mostly for trucking away the dirt. So the Rivanna Water & Sewer Authority plans to let the Rivanna Reservoir silt over for the next few decades while expanding the Ragged Mountain Reservoir.

Although several environmentalists consider this an environmentally sound plan, another group of greenies calling itself Citizens for a Sustainable Water Plan– made up of a former mayor, a former vice mayor, and a former chair of the RWSA– say that dredging is not only the cheaper option, it's also more eco-friendly.

That's because the new mega-reservoir would require clear-cutting nearly 135 acres of the Ragged Mountain Natural Area (180 if you include access roads), an area Edgar Allan Poe immortalized in a short story. Only a little of the harvested timber would be tall enough to be used for logging.

Additionally, the plan calls for a grand total of 9.5 miles of pipeline to pump water from the South Fork Rivanna Reservoir into the expanded Ragged Mountain Reservoir, with much of that pipeline running uphill. We're not sure how many kilowatt hours it would take to move water over that expanse, but what's for sure is that the water isn't going to run up a hill on its own.

Those are only the most predictable environmental consequences of the plan. That's ignoring the fact that I-64 would run on a bridge over the newly expanded reservoir. Twice over a three-month span last year, milk trucks overturned on I-64, spilling their contents all over the highway. Suppose a truck carrying more harmful cargo had an accident over the reservoir, a scenario that's more likely during colder months when bridges ice over.

However ecologically unsound the plan may be, its implementation seems almost inevitable. According to recent emails obtained by the Hook through a Freedom of Information Act request, Charlottesville City Manager Gary O'Connell declared on February 15 that the project enjoys the support of "a solid majority of our citizens" (the Hook knows of no referendum or survey the City conducted to arrive at such a conclusion) and that "I have gotten no public [nor] private direction from Council to change course. Full steam ahead."

It's a great way to buy fresh produce, but are local farmers' markets like Charlottesville's own City Market really the best way to keep the atmosphere fresh?

FILE PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

Localvore movement doesn't necessarily mean greener living

Local produce travels 60 miles, while grocery produce averages 1,600 miles. Too bad the latter is more fuel-efficient.

That's what the Boston Globe revealed last July in an article called "The localvores' dilemma."

"All things being equal, it's better if food only travels 10 miles," Peter Tyedmers, an ecological economist at Nova Scotia's Dalhousie University, told the paper. "Sometimes all things are equal; many times they aren't."

Why, exactly? Picture 311 pickup trucks, station wagons, SUVs, and sedans converging on the parking lot between Water Street and South Street each week during the warm months, each bearing just a few bushels of fruits and veggies.

Such analysis was lacking in a March 20 Daily Progress story in which a reporter and headline writer seem to believe that "local produce saves energy in a huge way."

However, what follows is a horror of fuel consumption about what happens with local produce: the average farmer's market vendor, like those at the City Market in downtown Charlottesville, travels 60 miles for each visit.

UVA fourth-year Lauren Doucette found in conducting research for her senior thesis that the Market burns through as much energy as 18 homes.

Suddenly, that lone 18-wheeler driving its giant load from the American Midwest or California doesn't seem so bad.

Still, she says, the math is a little more complex than it seems.

"Depending on the Farmer's Market, vendors expend about 4,000 to 6,000 kilowatt hours getting to and from," she says. "I called the local Harris Teeter and found that they get shipments from 14 trucks weekly, all coming from their distribution center in North Carolina."

Lots of people in Charlottesville wouldn't dream of getting their tasty greens from anywhere other than community-supported suppliers like Best of What's Around in Scottsville, Ploughshare in Louisa, Horse and Buggy Produce in Charlottesville, and of course, the City Market. But while there are a lot of great reasons to buy locally, fuel efficiency is not one of them.

If you still want to buy locally, the Piedmont Environmental Council has compiled a fairly comprehensive list of CSA outlets– check buylocalcville.com.

The Meadowcreek Parkway will run directly through McIntire Park, one of the largest remaining green areas in Charlottesville.

PHOTO BY LINDSAY BARNES

Meadowcreek Parkway means paving over green space

After decades of debates, resolutions, petitions, and public meetings, contractors last month relocated several utility poles in anticipation of the Meadowcreek Parkway– the first physical work on the project since it was proposed.

"Right now we're completing utility relocations, making the final land acquisitions, and advertising for bids for the project," says VDOT spokesperson Lou Hatter. "We expect to break ground in spring 2009."

The new road will run from the intersection of McIntire Road and 250 to Rio Road near Dunlora and CATEC. If construction moves according to schedule, motorists could be driving on the new road as early as spring 2012.

If the new bypass becomes a reality, it will run directly through McIntire Park, one of the largest remaining green spaces in the Charlottesville city limits. But that won't happen if Rich Collins has his way.

"Federal law says you can't use federal money in a project that takes park land for public use unless there is 'no prudent or feasible alternative,'" the longtime community activist says. "The courts have interpreted this to mean a highly stringent bar."

According to Collins, that's why the project is, technically, three separate projects. The interchange at McIntire and 250 is the only portion being funded by the feds, courtesy of a $29.5 million earmark passed by Sen. John Warner (R-VA). The state, city, and county will foot the rest of the $68.5 million bill, the City portion called "McIntire Road Extended."

But that's just one front on which Collins and others continue to fight the project.

"The Virginia Department of Historic Resources is concerned that the city hasn't done all it can to mitigate the effects on the park, since it's eligible for the National Registry of Historic Places," says Collins. "So now, we have a state department joining with lowly citizens."

Still, Hatter says any holdup in the proceedings would be news to him.

"We're moving forward with it," he says. "We have schedules for advertisement, construction, and completion. It is happening."

#