COVER- Smoldering truth: Ashley Mauter's fight and a shocking fact about smoke detectors

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

A year after a fatal blaze on Lewis Mountain Road killed a young man and critically injured his girlfriend, the fire's other survivor has dropped a bombshell. Contrary to news reports immediately following the blaze, the man insists that a smoke detector in his apartment was working that night and awakened him– it just didn't awaken him in time to give his sleeping friends enough time to escape. This new information contradicts the conventional wisdom that a working smoke detector could have saved everyone, and one fire official has a theory why.

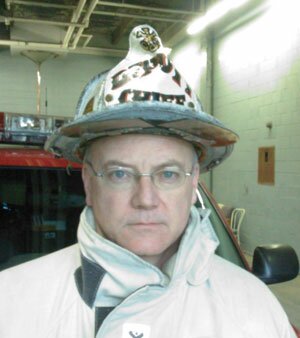

Boston Deputy Fire Chief Jay Fleming is on what he calls a "one-man mission to save as many lives as possible," to teach people that having a smoke detector, while critical, is not enough. He says that having the right kind of smoke detector is what matters.

If his theory is right, thousands of Charlottesville area residents, including people with working smoke detectors, may not have time to escape a deadly fire in their own homes.

***

Ashley Mauter, the surviving Lewis Mountain Road victim, knows the terror and pain of a fire all too well. Looking at the blue-eyed, 25-year-old young woman, her smooth face framed by long red hair, it's almost impossible to imagine the suffering she describes– until she rolls up her left sleeve and removes her shoes.

Instead of the flawless skin she once took for granted, her left arm and both her feet– indeed, much of her left side from shoulder to toes– is a mass of scar tissue, in places more resembling melted wax than human flesh. Her right side, spared by the fire, is scarred as well, a result of surgeons harvesting her healthy skin for grafts. Thirty percent of her body was initially damaged by flames, but a full two-thirds is now marked in some way by the event that forever changed her life.

That she's alive at all is something of a miracle, according to her doctors. Her burns, though shocking, were not the most life-threatening of her injuries. Instead it was the searing smoke that damaged her lungs, the carbon monoxide poisoning that, depriving her brain of oxygen, incapacitated her and kept her from escaping on her own.

Her boyfriend, 25-year-old Brett Quarterman, suffered less severe burns than Mauter, but he– like the two victims of the 2003 Clifton Inn fire and the victim of a January fire on Woodlake Drive in Albemarle County– died of carbon monoxide poisoning.

The horrifying danger of carbon monoxide, Chief Fleming in Boston says, is the reason it's critical to install the right kind of smoke detector.

A tale of two detectors

There's no doubt that smoke detectors save lives. Since their introduction to the mass market 30 years ago, fire-related deaths have dropped by about half, according to an industry association. But while only one or two brands of smoke detectors were originally available, these days it's a different story.

Anyone taking a trip to Lowe's to pick up a smoke detector might be overwhelmed by the choices. Most of the dozens of detectors for sale are certified by global consumer testing corporations such as Underwriters Laboratories, so it might seem logical to just pick the cheapest. After all, the consumer product experts say they all work, right?

Wrong, says Fleming, who contacted the Hook after reading about the Lewis Mountain Road fire.

There are two types of smoke detectors, and they operate on different principles. The first type– ionization detectors– use a small amount of radiation. They're best at detecting the small particles typically produced by active flames, and they're significantly cheaper– several models can be purchased on Amazon.com for $5.99.

The other type, photoelectric detectors, use a beam of light like the finish line of a race course, and are activated by smoke particles intruding on the beam. Starting at $14.99 on Amazon, they're nearly triple the price of ionization detectors, but Fleming says the benefit is priceless.

Both types of detectors can eventually sense either type of fire, and he admits that ionization detectors sense open-flame fires, like those that start in kitchens, faster than photoelectric– but only by less than a minute.

Fleming says photoelectrics are far superior at detecting the larger particles typically produced by smoldering fires– fires that haven't yet erupted into full flame. He says photoelectrics can warn of a smoldering fire as much as 30 minutes before an ionization detector goes off, and those fires, he notes, are the ones that typically kill people with deadly exposure to carbon monoxide while everyone's asleep at night.

"Wouldn't you want a 30-minute head start?" he asks.

That 30-minute lead time to escape smoldering fires isn't photoelectric detectors' only advantage, Fleming says. Numerous studies confirm that ionization alarms, particularly ones placed near kitchens, are far more prone to false alarms, and these so-called "nuisance alarms" are the leading reason people disable detectors, according to the National Fire Protection Association. And a disabled detector can be a step toward tragedy.

That may have been the case in the January 26 fire on Woodlake Drive, where, according to Albemarle fire officials, the detector in the Four Seasons townhouse of 46-year-old Gregory Edward McMullen was not functioning.

As evidence of how quickly carbon monoxide can be fatal, a napping McMullen awakened to smoke and was able to call 911 from his bedroom, where he was trapped by the fire that officials believe was started downstairs by candles. That was 7:43pm. Even though firefighters arrived at 7:48pm, just five minutes later, it was too late for McMullen. He had died of carbon monoxide poisoning.

According to Albemarle fire investigator Bill Clark, the Department couldn't hear an alarm during McMullen's 911 call. Although family members allegedly told him there was a smoke detector upstairs, Clark says investigators never found it, so they couldn't determine the type or whether the battery was properly inserted. The Emergency Communications Center declined the Hook's request for a copy of the 911 tape, citing the the need to protect McMullen's family and the "personal nature" of the call.

Although the answer about McMullen's detector may never be known, Fleming suspects that it– like more than 90 percent of detectors in houses across the country– was an ionization model. He believes the tragedy might have been avoided had the apartment been equipped with a photoelectric, which could have given McMullen time to escape. Fleming says using photoelectric detectors is most critical in small apartments or mobile homes where it's impossible to install a detector far enough from the kitchen or bathroom (as ionization detectors can also be triggered by steam) to prevent frequent nuisance alarms, which lead people to disable them.

Massachusetts already mandates photoelectric detectors near kitchens and bathrooms, and a study conducted in Alaska showed that in small homes, ionization alarms were eight times more likely than photoelectric to be disabled as a result of nuisance alarms.

National Fire Protection Association spokesperson Lorraine Carli says her Quincy, Massachusetts-based organization is doing research now based on Fleming's theory and will change its recommendations if its own research supports a switch. For now, however, the Association is promoting detectors that offer combined ionization/photoelectric capability since, as she says, "You don't know what type of fire you're going to have."

What are local departments doing? Both Charlottesville and Albemarle have free smoke detector programs. Anyone can call and request devices, and the fire departments will come install them. Charlottesville, however, seems to be a step closer to Fleming's dream, offering combination detectors, the type recommended by the NFPA.

In addition, according to Charlottesville fire chief Charles Werner, his department goes beyond simply making smoke detectors available; it's systematically contacting every household in the city to ensure functioning detectors are in place. If the department can't reach a resident by phone, firefighters will visit the house to ask in person.

In Albemarle, Assistant Chief of Fire Prevention James Barber says the department is distributing ionization alarms, since they still have a supply. When those run out, he says, Albemarle FD will begin offering combination detectors.

Although proponents of combination detectors say the devices provide the best of both worlds, Fleming insists that photoelectric alone is still preferable, since the combination detectors are as prone to nuisance alarms as ionization-only models. He points to several European countries' reliance on photoelectric detectors as proof that they're enough on their own. Australian fire chiefs recently followed suit and now recommend only photoelectric detectors, and the state of Arizona also recently modified its smoke detector policies to promote photoelectric detectors.

The one concession Fleming makes toward ionization detectors: they're better than no detector at all. Anyone who doubts that can look to the fatal November 14, 2003, blaze at the Clifton Inn.

After a storm blew through Albemarle County the previous night and knocked down power lines, employees at the Inn lit candles. What many Clifton guests apparently didn't realize was that all the Inn's employees had departed for the night with no one watching over the candles or the fireplace. Sometime after midnight, something ignited furniture in a downstairs sitting room.

Upstairs in the guest rooms, unfortunately, the smoke detectors were not functioning, and some of the Inn's windows had been painted shut.

As smoke and carbon monoxide poured into rooms, several guests were able to escape, and one unconscious woman was rescued by fire-fighters from a first-floor bedroom.

But two women upstairs were not so lucky. Trish Langlade and Billie Kelly, two law school recruiters, wives, and mothers of young children, perished from carbon monoxide poisoning.

There were tragic similarities to the scene that unfolded less than four years later on Lewis Mountain Road.

Soul mates

It was at a party in July 2006 when Ashley Mauter met Brett Quarterman. He was by himself, leaning against a keg, when Mauter walked up to fill her cup. "I joked, 'a little drunk there, buddy?'" Mauter recalls. The interaction ended there that night, but the next time the two met, at a gathering the following week, they started a conversation that launched a relationship.

"We just hit it off," Mauter recalls. "We didn't talk to anybody else the whole night." Within days, Mauter says, "We knew we wanted to build a life together."

The intense connection wasn't inspired only by how much they had in common, though Mauter says they had similar quirky senses of humor and both loved animals and the outdoors. In fact, the differences between them might have even seemed stark.

Quarterman, a devout Christian, was a highly motivated 2005 Virginia Tech graduate who'd moved to Charlottesville in 2006 to take an engineering job. Mauter, who considers herself spiritual but not religious, had dropped out of community college in Northern Virginia and was working in restaurants, "a little lost," she admits, and trying to figure out what to do with her life.

Soon after their meeting, she enrolled in nursing classes at Piedmont Virginia Community College, and in the evenings, Mauter says, an encouraging Quarterman would sit with her as she studied.

Mauter didn't tell her family she'd returned to school– "I wanted it to be a surprise," she says– but her mother, Kathy Young, says that even without knowing of her daughter's enrollment, she could see Quarterman's positive influence.

"It was something special," says Young, who lives in Centreville. "All of a sudden, she was always cooking dinner instead of in bars."

The couple hiked together, painted together, and along the way, documented their relationship with photographs on almost every occasion. The shelves and walls in Mauter's two-bedroom apartment on Georgetown Road are covered with photos of the laughing couple– and with artwork they created together. Their brightly colored abstract paintings, Mauter says, are a reminder of the joy Quarterman brought, and of his artistic talent. Around her neck is a necklace he made for her with coins they'd left on tracks to be flattened by an oncoming train.

The memories are sweet. And unbearably painful.

"I saw fire everywhere"

St. Patrick's Day conjures thoughts of leprechauns, shamrocks, and celebrations in green. At 2015 Lewis Mountain Road, where Tom Stith shared a duplex apartment with another UVA graduate student, just such a party was under way on the evening of March 17, 2007.

According to Stith, it was a lively gathering of close friends who were hanging out on the porch, snapping goofy pictures, drinking beer, and enjoying appetizers. Among the 20 or so guests that night were Mauter and Quarterman.

"You never saw one without the other," says Stith, Quarterman's best friend since sixth grade.

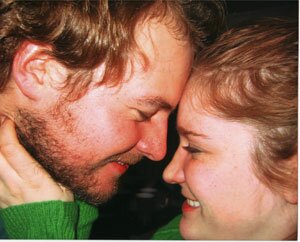

Photos taken of Mauter and Quarterman that night show the couple in typical poses– hugging, kissing, making funny faces. "We couldn't keep our hands off each other," Mauter recalls.

By around 2am on March 18, nearly all of the guests had gone home except Mauter and Quarterman. Although they each lived nearby, they called a cab, but missed it when they lingered inside too long as Quarterman played a video game. Rather than calling a second cab or chancing a DUI, they decided to play it safe by staying at the apartment.

Stith headed to his girlfriend's apartment to spend the night, leaving his room open for his friends to crash.

That last-minute decision saved Stith's life, ended Quarterman's, and changed Mauter's forever.

In the second bedroom, the apartment's other resident, Mark Allen, awoke just before 3:30am– about 45 minutes after he'd gone to sleep following a brief, post-party clean-up. He smelled smoke and, contrary to previous news accounts that claimed the only detector was in an attic, he says he heard the smoke alarm beeping in the hallway. He didn't need to look far to find the source.

"The majority of the right-hand side of my room was on fire," Allen says. "The area beside my bed, my night stand, ottoman– it was all in flames."

Although his first fear was that he was trapped, that wasn't the case. Allen raced to Stith's bedroom down the hall, banged on the door, then pushed it open. He says he saw two people get out of bed, although he didn't initially realize they were not his roommate and his girlfriend. Having alerted them, he returned to his room hoping to extinguish the blaze, but he quickly realized his effort was futile.

"The flames had started up the headboard of my bed," he says. They then jumped to the wall and ignited posters. "I was covering my mouth with my blazer," he says. "Flames were actually traveling into the hallway at this point."

As Allen looked on in horror, the hallway ceiling– with the still-beeping smoke detector attached– collapsed. He raced outdoors to bang on the neighboring apartment's door. By the time he returned to his own apartment, the heat and smoke were so overpowering they prevented his reentry. When firefighters arrived moments later, Allen had made a terrifying discovery: Mauter and Quarterman were still inside.

Rush to rescue

The call came in to the fire station 10 on Ivy Road at just after 3:3oam. Within moments, firefighters were pulling out, racing to Lewis Mountain Road. There, they found flames shooting from two windows in the building, thick billowing smoke, and a desperate young man in the yard yelling for his friends.

Captain Mike Johnson was among the firefighters who entered the inferno. Inside, he says, the heat was intense and visibility nonexistent. After battling through the blaze in the living room, Johnson and fireman Lance Blakey reached the couple, who were unconscious in the bedroom, and passed them through a window to firefighters and EMTs outside. Mauter was breathing shallowly, but Quarterman had stopped breathing and had to be resuscitated twice before reaching the hospital.

Across the continent, Mauter's older brother, 27-year-old Ryan Mauter, was asleep in his Denver apartment when the phone rang around 2:30am Denver time. Because his sister had listed him as an emergency contact the last time she'd visited UVA hospital, his was the only number nurses had.

Ryan Mauter missed the call, but was awakened by the ringing and checked his voice mail.

"It was a message that reduced me to being a child. It was so morbid," Ryan recalls. "They said, 'We believe we have your sister here; there's been a house fire. We need family involved immediately."

He phoned his father, who also lives in Colorado, as well as his mother and stepfather in the Northern Virginia town of Centreville. Within hours, Mauter's family– Ryan and his father on a private jet provided by a friend– began arriving at UVA, terrified of what they would find.

They weren't alone in their devastation. At home in Blacksburg, Quarterman's parents had received a similar message and were quickly on their way to UVA Hospital. Members of the Charlottesville Fire Department, including Chief Werner, arrived from Lewis Mountain Road, concerned about the fate of the couple they'd rescued.

Two days later, Quarterman lost his struggle for survival, becoming the City's first fire death in a decade. It was something Werner, a 30-year veteran of the department, hoped he'd never face again.

"It was obvious how sincere and upset he was," says Young of Chief Werner. "It really tore him to the core."

Slow recovery

To allow her damaged lungs to heal, doctors induced a coma and placed Mauter on a ventilator. Her awakening, one month later, was especially difficult. Because of the pain killers– and perhaps from some remnant of carbon monoxide poisoning, her family theorizes– she was confused and even hallucinating.

"I thought I was dead, and that I was in hell," says Mauter. "I thought the people I loved were really demons pretending to be them."

Watching his sister suffer was its own kind of hell, says Ryan Mauter.

"She didn't understand what was going on; she was flailing around, her eyes were cloudy," he recalls. Even though she had awakened, her prognosis was still uncertain.

"She might not live, she might have severe brain damage, she might lose her foot," he says doctors told him. "Every time she moved, we were trying to interpret it. It was mind-numbing."

Still, in the midst of the darkness, Ryan Mauter and Kathy Young say they were touched by the care that not only Ashley received but also the care extended to them by emergency professionals. The ICU staff, they say, was "amazing."

With her horrific injuries and hallucinations, Mauter was in no state to be told of Quarterman's death.

"We struggled with how and when to tell her," her mother recalls. But eventually, Mauter– who had improved enough that she could communicate by writing in a notebook while her breathing tube was still inserted– demanded an answer about Quarterman from a visiting friend. That friend left the room to fetch Young, who, after consulting with doctors and nurses, relayed the heartbreaking facts to her daughter.

Mauter's recollections of hearing the news are foggy.

"I remember seeing Tom [Stith] the next day," she says, choking up, "holding his hand."

Mauter remained at UVA hospital until early May, undergoing agonizing wound cleanings in "the tank room," a facility equipped with steel table and hoses. Although she was given pain medication before the procedures, having nurses peel away the dead tissue to reveal raw muscle was excruciating, Mauter says. She had suffered third degree burns– wounds that penetrate all skin layers. Surgeries added to her pain, although she says she is luckier than some burn victims because her body didn't reject any of the skin grafts, a success she attributes to the skill of her plastic surgeon, Tom Gampper.

In May 2007, Mauter was well enough to leave the hospital and move to HealthSouth, where she underwent another month of inpatient therapy and began to learn to walk, talk, and live again.

Staying strong

A year after the fire, Brett Quarterman's parents sent a message that they are still too devastated to speak about the accident. Ashley Mauter's physical wounds are nearly healed, but her scars will remain with her for life.

Fire officials never pinpointed a cause for the Lewis Mountain blaze, although they believe it started in Allen's bedroom, where Allen says there were neither candles nor cigarettes. One fire investigator suggests it could have been an electrical fire. Awakening to find his room fully engulfed in flame was the most frightening experience of his life.

"Even a year later, I relive it," he says. "I can still remember the smell and the heat." Still, Allen says, his trauma pales before Mauter's.

"I'm not the one who has to live without the love of my life," he says. "I'm not the one who's been burned over a third of my body."

In the midst of the most unimaginable horror and grief, Mauter has, however, found another soul mate of sorts: her mother. Young took a leave from her job as a sixth-grade teacher in Centreville to move in with her daughter to offer her support.

"At first, I was like, 'Oh god, living with my mom again,'" says Mauter, who concedes the relationship hasn't always been smooth. "But it's been so great; now I don't want to see her go."

Mauter's primary care physician, Sean Reed, says he's impressed with her progress.

"I remember distinctly when I met her, being overwhelmed by the raw human tragedy she'd been through," he says. "I think she's working hard at rediscovering herself, redefining herself."

Taking art classes, Mauter has created a variety of new pieces– a colorful mosaic, several water colors– that join the artwork she and Quarterman created together on the walls and tables around her apartment.

Future surgeries may be scheduled to improve her flexibility. But if much remains uncertain, she's sure about one aspect of it: she'll remain an advocate for fire safety, sharing her story, showing her scars, hoping to prevent anyone else from suffering a similar ordeal.

"You see things like this in movies and you think, 'It's never going to happen to me,'" she says. "I just want to grab people and shake them. It doesn't take much to put batteries in the detector."

Boston's Fleming agrees with Mauter, but he hopes people will go a step further– putting batteries in the right kind of detector. For Fleming, that can only be one kind: photoelectric.

Correction: Ashley Mauter graduated from high school and took some community college classes in Northern Virginia.–ed

Ashley Mauter will likely undergo more surgeries in the future to help with mobility, since scar tissue can tighten over time and inhibit movement.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"Before this I was working to survive. Now I realize that I could be gone any minute, and so could any one of my loved ones," says Mauter, who is considering becoming an art therapist or a burn tech to help others deal with severe burns.

PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

"We were soul mates," says Ashley Mauter of Brett Quarterman, seen here in a photo taken just hours before the fire.

PHOTO COURTESY ASHLEY MAUTER

On March 18, 2007 a fatal fire raged through this duplex on Lewis Mountain Road.

FILE PHOTO BY HAWES SPENCER

The death of Brett Quarterman two days after the fire on Lewis Mountain Road– the city's first fire-related death in a decade– was "devastating," says Charlottesville Fire Chief Charles Werner.

FILE PHOTO BY JEN FARIELLO

Jay Fleming, deputy chief of the Boston fire department, believes thousands of lives will be saved if states mandate photoelectric smoke detectors in place of ionization detectors.

PHOTO COURTESY JAY FLEMING

#

12 comments

The information about the two kinds of smoke detectors is eye-opening. I own several rental houses for college students in Ohio and I will make sure we also have those kinds of detectors!I Ashley is my neice and this article is tremendously written. It truly captures all aspects of Ashley's tragic, but triumphant journey. Her story makes us all evaluate our oen circumstances and realize that we need to do a better job to appreciate each minute God has given us on this earth!

Thanks for writing this story, Courteney. I hope it brings more attention to smoldering fires.

One addition about the photodetect alarms: most Lowe's and Home Depot only stock the ionization type lately because they're $5 cheaper and people don't know to buy the combo or the photodetect type. But you can still get good quality photodetect alarms from places like Amazon.com

Mike Dayoub

SmokeShutoff.com

I am so happy that you printed this story, I feel that we should all be aware of our fire alarms in our home, and check them often. It is such a sad story and should help everyone appreciate thier own lives and the everyday things and people we tend to take for granted. My heart, and my prayers go to Ashley and her family. God Bless

A big thank you to Courteney for pulling together so much information and writing such a tremendous article. The only other thing I think Ash would want you all to know is that she did graduate from high school but did , at one point, drop out of community college in Northern Virginia. I hope all who read this will never experience what Ashley, our family, and the Quartermans have.

Ashley's mom

Thanks Kathy, and my sincere apology to Ashley-- I misunderstood and have corrected the story online. I'll also run a correction in the paper this week.

Thank you for such an eye opening story. Ashley, you are such a beautiful girl and an inspiration. Continue your recovery. Hope to meet you one day. (A friend of Allison)

A very well written story. My best to the families.

Every [rental] house I've lived in here in Charlottesville has lacked even one smoke detector. I've done property management in my home state and I am shocked at what property managers get away with here. It was illegal in other states not to have working alarms -- you'd get shut down just for that.

Sara,

Great point!!!! Charlottesville needs to change their codes especially with landlords renting property to college kids. You can't take short-cuts when it comes to safety--HEY CHARLOTTESVILLE WHAT IS IT GOING TO TAKE FOR YOU TO GET SERIOUS AND MAKE SOME CHANGES-- Since the landlords are making lots of money from students--you think they could bring their property up to code

Courtney,thanks for an eye-opening story and for identifying some important safety deficiencies facing our college students. Looks like you might have the opportunity for a follow-up report to raise the awareness and complacency of the folks in the city reponsible for ensuring building safety.

Your information on Ashley is a great start and hopefully will be the last article you need to print on this topic. If safety requirements are established and enforced, this type of tragedy can be prevented from happening in Charlottesville again.

ashley this is wendy from uva.............

you are awesome and I am so proud to see how far you have come. I am so glad you and your wonderful mother have a wonderful relationship now also. Keep up the good work.

Prior to publishing quotes in your article about carbon monoxide, I suggest you recheck your sources and their veracity. The quote you have attributed to me, that I disabled the CO detector is totally incorrect, and leaves you open for liable.

This story paits an amazing picture of two of the most amazing people I have ever met! Brett was a very special person to my husband and I. He and Ashley were no question made for eachother and she holds a very special place in my life. Thank you for this story and for the work that will be done by getting this story out there! Ashley, we love you and pray for your recovery daily. I hope that people can learn from this story and prevent this tragedy from happening to anyone ever again!

**Gone but NEVER forgotten!! We love you Brett!**